1

It’s a February evening in 2014 at the height of the dry season. Even the flies are too exhausted to buzz. They spiral around for a few seconds and then stop.

Soon it will be midnight in Bonamoussadi, a residential neighborhood to the north of Douala. Around the Bijou bakery, a few blocks from our house, bars are closing with a clatter of chains and padlocks. Drunkards bleat for one last beer: “Otherwise we’ll sma-sma-smash up this place!” The women bar owners shriek with laughter and send them packing: “Off with you! Out of here, you drunken fools!” Their laughter sounds like a wailing police siren. A hundred meters away, on the main street, the popular Empereur Bokassa bar pounds out the season’s hits. You can hear the distant concert of croaking and the mewing of stray cats.

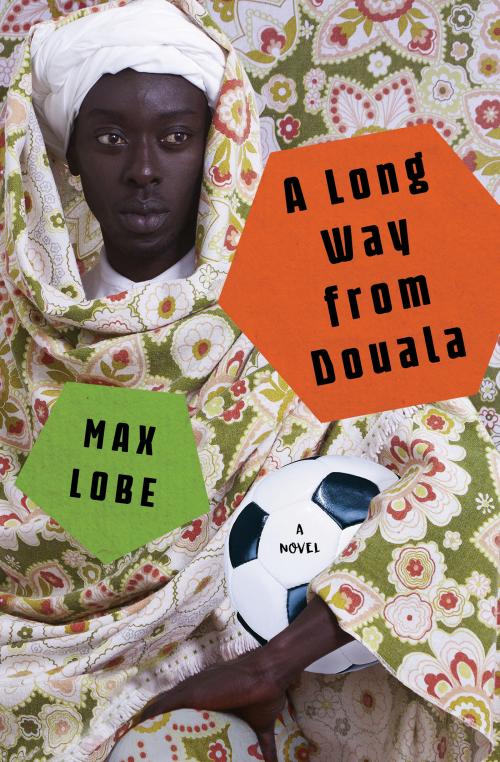

Meanwhile, I’m glued to my desk, revising for my first-year university exams. The bedroom walls are plastered with posters of football champions: my brother Roger’s idols. I only recognize the photo of our national team and the one of the legendary Roger Milla. A few aluminium trophies, some cheap medals and countless sports shirts that my brother can’t be bothered to put away. His boots stink.

Our bunk bed is opposite the desk. It’s more and more cramped for our growing bodies. Roger’s asleep on the top bunk, worn out from his secret training sessions. My mind keeps wandering from my books and I gaze fondly at his angular face. I can see Pa in him. They have the same high forehead, hollow cheeks and pointed chin. He’s snoring. I can see his dreams of football stardom dissolving in the saliva dribbling from his open mouth. I feel sorry for him and wish that Pa and Ma would stop forcing him down a path that’s not right for him. He was born for football. He often tells me excitedly, his eyes shining, “You’ll see, little bro! I’m going to make it big! My transfers will cost millions. They’ll want me to do trainer ads. Adidas, bro! Adidas! I’ll end up on the cover of Paris Match. Just you wait! Just you wait!”

Suddenly, Ma’s voice hysterical from the next bedroom: “Claude! No Claude, you can’t do this to me! No! Get up right now! Get up and walk, in the name of the Lord Jesus!”

Roger’s eyes snap open: “Did you hear that?”

As one, we rush in to find Pa lying on the bed. His breathing is very shallow. Hard to know whether he can even still feel his legs. He’s barely moving. Part of his face is paralyzed. His left eye’s shrunken and closed, and the other one’s bulging. His mouth’s all lopsided and only opens on the right side.

Pa is unrecognizable.

Muttering a string of prayers, Ma’s massaging him with her precious Puget olive oil imported from France.

Oh Lord! Why not get him straight to hospital? No, no. Ma believes in the all-powerfulness of Yésu Cristo! Despite Pa’s aversion to the unction, which she paid dearly to have blessed by Pastor Njoh Solo of the True Gospel Church, here she is pouring long, long streams over his cheeks, his shoulders, his whole body. Dousing him all over. She even tries to get him to drink some, but it’s no use. Everything that goes into his mouth comes straight out again. Ma’s distraught. Has her God abandoned her? Impossible! That’s not His way. Maybe the old man can’t swallow because it’s olive oil, she tells herself. So she runs to fill a glass with water. The water Pa brings home in vast quantities from the SABC, the Cameroon national brewery where he works. Ma had a few liters blessed by the pastor. Convinced that witches were against her marriage, she says it was to ward off evil spirits. But Pa isn’t able to swallow that water either.

So Roger fetches some beer, goes over to Pa and raises him up slightly. Our father’s bulging eye twinkles at the first drop. He seems to be smiling. He’s like a child whose mother gives him mandarin-or mango-flavored cough linctus. But once again, like with the olive oil and the water, nothing; it doesn’t work. The liquid’s barely past his lips when it froths out again. The only thing left is the Bible, says Ma: “Oh Lord Almighty, thou who givest life, deliver my husband from death in the name of Jesus Christ!” But the more she invokes Yésu Cristo, the more contorted Pa becomes.

She panics and wails: “Oh Good Lord! What have I done to deserve this? Why do you punish your poor servant like this?” Roger kneels beside Pa while I calm our mother down. At that moment, an ocean lies between my brother and me.

Roger rushes out, slamming the door. Ma screams: “Where do you think you’re off to?”

What feels like an eternity later, he reappears with our brother-from-another-mother Simon Moudjonguè. On seeing me still sitting beside Ma, Roger clenches his jaw and beckons Simon to come closer. Simon acknowledges me with a nod. His discreet greeting is a question: “What’s the matter this time?” Roger takes hold of Pa’s right shoulder. Simon helps him. His eyes are shining with resolve. Only his hands are shaking. The two of them carry Pa outside to the waiting taxi.

We’re all on edge. Is Pa still alive? Ma keeps yelling: “Where are you taking my husband, Roger?” Then she adds: “Simon! Simon, answer me!”

A few shadowy figures gather under the wan light of the street lamp. The neighbors. Both curious and concerned. Two drunks stagger over to join the knot of women. They yell: “Hey you! You . . . You haven’t got a nice, cool little bottle of Cas-Castel, have you?”

Roger’s chest frantically rises, falls and rises again. He’s sweating, he wipes his forehead. Once inside the taxi, he lays Pa’s head in his lap. Simon, in the front, shouts at me: “To the General Hospital!” As it drives off, the car stirs up a great cloud of dust. Ma collapses. The neighbors come and help me support her. One of the drunks clears his throat then hums: “You drink ’am, you die, You don’t drink ’am, you still die!” His rasping voice mingles with the croaking and mewing.

And that’s how Pa died.

2

Contrary to all expectations, a few months earlier, my brother had gained his school certificate. Granted, it was his fourth attempt. At the same time, I’d passed my baccalaureate, at the age of seventeen, following in the footsteps of Simon, who was already at university.

To celebrate Roger’s school certificate and my baccalaureate, our parents threw a big party, to which they’d invited family and neighbors. Our brother-from-another-mother Simon had come from Ngodi-Akwa, across town, to help out. We stacked the crates of beer that Pa brought back from the SABC in the kitchen. Pa capered about like a mountain goat: at last his son had passed his school certificate!

We’d given the sitting room a thorough spring-clean and arranged chairs against the walls to free up a big space in the center. For dancing. The only chair that stood out was Pa’s armchair, recognizable both because of its imposing size and the slightly old-fashioned charm of its carvings.

Our local chief, Pa Bomono, and his wife had ringside seats. They wouldn’t have missed that party for anything in the world. You should have seen them! They wore their finest traditional costumes. He, a white shirt with a silky black pagne tied around his hips. She, a voluminous ankle-length dress with wide sleeves: the kaba ngondo. When Pa complimented them on their outfits, the delighted Pa Bomono had replied: “Oh my brother Moussima! In this neighborhood, it’s not every day that we see boys of barely seventeen obtain their baccalaureate, is it!” Pa laughed grudgingly while Ma admired Ma Bomono’s kaba ngondo. “Thank you. Thank you very much, sister. It’s for our son Jean’s baccalaureate,” Ma Bomono replied, revealing the gap between her teeth.

Everyone was there, even the women my mother described morning, noon and night as witches envious of her marriage. The youngest of them, the panthers, wore little clothing. Ma Bomono was shocked: “What is this way of dressing? Anyone would think the market was out of fabric!”

The owner of the Empereur Bokassa had briefly shut the bar. She’d been followed by a few drunkards, desperate for the slightest drop of free alcohol. They’d installed themselves on the porch, near Roger’s friends, who were lustily eyeing the panthers’ plunging necklines. They talked not of their buddy’s school certificate, even less of my baccalaureate, but of their exploits and the upcoming matches of their football team, the Nyanga Guys of Bonamoussadi.

Simon’s mother, Sita Bwanga, arrived a little later. She parked her blue Toyota RAV-4 in front of our iron gate and started hooting the way people do on their way to a wedding. Jesus! Anyone would think Cameroon had just won the Africa Cup of Nations. Ma and the other women went out to greet her. You should have seen them dancing, clapping their hands and singing: “O wassé! O wassé! Here we come! Here we come!” Sita Bwanga pulled several boxes of champagne out of her car. Moët. “It’s to celebrate our son’s baccalaureate!” she announced, while the women ululated continuously as they do at bride-price ceremonies.

And Ma yelled: “Where on earth has that lazybones Roger got to? Tell him to come here and carry these boxes!”

My parents had laid on food: banana fritters, fried plantain, a delicious sauce of red beans with palm oil and chicken wings roasted with tomatoes. Raising a spoonful of sauce to his lips, Pa Bomono stained his white shirt. “You’ll eat yourself to death!” snapped Ma Bomono, glaring at him. This was met with hearty laughter. Ma turned to Roger: “Can’t you see we need a cloth to wipe it off ?” I know Pa wanted to speak up in Roger’s defense. After all, it was his Roger. But how could he? Ma would kill him!

Pa had brought out our entire stock of beer. Simon, Roger and I had the job of serving. We ran to and fro between the kitchen, the living room and the porch. Our hi-fi pumped out old Makossa hits: our parents’ favorites. A few women neighbors of their generation, also wearing kaba ngondos, had begun shimmying in the empty space at the center of the room. They looked like they were showing off: you can’t dance the Makossa without showing off.

On the porch, meanwhile, the panthers and the football guys were getting all huggy-huggy in a very suggestive way. Luckily they were far from the eyes of the older folk, otherwise Ma Bomono would have given them a piece of her mind.

There were outbursts of laughter, sometimes shrill, sometimes booming. Glasses and plates were knocked over, broken. Roger, Simon and I would rush over to clear up, collect the shards and scraps of food. As we passed, the guests called out to us above the din: “Hey you! Na how ’na? Where’s my beer? I’ve been waiting ages! Is it coming or not, jooor?”

Our house had turned into a giant bar.

In the living room, Sita Bwanga was sitting next to Ma. They were whispering in each other’s ears like two teenage girls, and they’d burst out laughing throatily, slapping their hands together. Tos-tas! Over the general buzz, I heard Sita Bwanga say to my mother: “It’s our sons Jean and Simon who are going to elevate us in this country.” And they hooted again.

Regardless of his state of advanced drunkenness, Pa said to Roger: “Son, mix me my . . . my beer with the palm wine that Pa Bo-Bomono brought.” He took a good swig of this mixture then burped: “Ah, my son! Moët, compared with this, I swear it’s . . . cat’s piss!” and there they were, Pa Bomono, Roger and him, rolling around laughing. What was so funny?

Pa wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. Then, suddenly, he clapped his hands to ask for everyone’s attention. “Oh God! What kind of speech was he going to make, in his state? Gradually, a hush fell over the room. Then Pa cleared his throat noisily, thrust out his chest and launched into a tirade punctuated with hiccups and plaudits: “My f-friends, thank you very much for being h-here in such large numbers to celebrate the baccalaureate of my deserving son Jean Moussima Bobé.” Applause smothered my surprise. Was it really me he was calling his deserving son?

“Truly, I th-thank you on behalf of Roger, too!” More applause and a smile from Ma.

“I am so p-proud of my son Jean. Look what one tiny seed from me has pro-produced. A genius! A NEinstein! A Socrates! And even a Barack Obama!” Bursts of laughter and never-ending ululations.

Ma shot Pa a scornful, annoyed look. Was he trying to highjack me, her star? Besides, hadn’t she told the whole of Bonamoussadi and far beyond that I, her Choupinours – her little teddy bear – was gifted? Hadn’t she said that her little Choupi had inherited her great brain? Noticing that my mother was looking a bit put out, her bosom-friend Sita Bwanga tapped her on the thigh: “Hey sister! No need to be angry about that, jooor? Men are all the same, you know: when it’s good, they say it’s all thanks to their seed alone, and when it’s bad, it’s always our fault. Let him talk his talk-talk as much as he likes. Come on, let’s drink our champagne!”

Even though they were already sozzled, the guests cracked open more and even more beers. With their teeth. They clinked bottles, drank straight from the neck then burped loudly. At one point, some of the guests began predicting a golden future, but only for Simon and me. “You, Jean, you’ll be the minister of shumthing very important in this country!” a woman neighbor with a shaved head struggled to articulate. “No, no,” argued the owner of the Empereur Bokassa from the terrace where she sat. “I’m certain Jean will be an important banker in the United States of America, or in Switzerland, like Simon!” “Johnny for President!” barked a drunk. Pa Bomono had a fit of hiccups that made him almost fall off his chair. Then he regained control of himself and breathed deeply. For him, not a doubt: I’d win a Nobel Prize! Whereas Pa hadn’t said a word, Ma and Sita Bwanga on the other hand, all emotional, their eyes gazing up at the heavens, repeated: “May the Good Lord hear you! Amen!”

Roger had retreated to the dining room. Stony-faced, he was fiddling with his phone when Simon and I joined him. “But my bro-brother Claude,” Pa Bomono said to my father, laughing. “Your seed, eh? You say it produces . . . er . . . that it produces geniuses . . . eh? But you’re the only one who thinks that. Because the streets are teeming with beer and football ge-ge-geniuses.” Ma and some of the women burst out laughing.

Pa bowed his head. Shame weighed so heavily on his shoulders that he slumped in his chair. This was going too far! He had to say something. He had to put things back in perspective. Dammit! The young Nyanga Guys of Bonamoussadi hadn’t appreciated Pa Bomono’s comments either and had made it known by shouting back. Threats to beat him up and curses were traded between them and the old folk. Fingers pointing straight as arrows. A hail of insults. Suddenly, Pa stood up, turned off the music and ordered the guests to leave. “Oh Claude Moussima! We haven’t even . . . haven’t even begun to celebrate Jean’s success and you’re already kicking us out? Na how ’na?”

“You can go and sleep off your beers in your own homes!”

“Can’ even have a li’l laugh here,” complained Pa Bomono lurching toward the door, followed closely by his wife.

“Everyone out!”

Even so, some of the neighbors congratulated me one more time: “Well done, Jean! Keep it up, my son!”

The lady with the shaved head spoke to my brother: “Ah Roger! Your turn will come, too. Just ask Jean and Simon to help you, that’s all. Jooor?”

Roger said nothing. He didn’t even look at the people who spoke to him. He ran straight to our room and Simon followed him. But he’d already shut the door. “Open up!” Simon demanded. “Open up, Roger!” No reply. He needed to be alone. Alone with his football kings and his dreams of fame and fortune.