INTRODUCTION TO THE 2023 EDITION

ON 28 NOVEMBER 2017, having traveled to Burkina Faso, French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech in which he expressed his will to rebuild the relations between France and Africa on new foundations. He had already spoken in the same sense on different occasions, acknowledging that the new partnership France wanted to build with Africans, with the continent’s youth in particular, was impeded by France’s history of colonialism, calling into question a relationship that needed repair. During his visit in Burkina Faso, before an audience of students at the University of Ouagadougou, Macron chose to focus on one aspect of the reparation of what he had himself called the colonial “crime against the human”: the spoliation, by violence, of African artefacts, taken from the continent to be stored in ethnographic museums in Europe. Recognizing that most classical African art was in European museums, he declared: “The African heritage cannot only be in private collections and European museums. African heritage must be promoted in Paris, but also in Dakar, Lagos and Cotonou, and this will be one of my priorities.”

Senegalese academic Felwine Sarr and French academic Bénédicte Savoy were then tasked by Macron with the mission of preparing a report on the issue. They completed The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage, Toward a New Relational Ethics in 2018. Following the report and after the French parliament granted legal authority to the required operations, France has now given back to Senegal and Benin objects that were taken by its soldiers as spoils of war: a sword that belonged to Senegalese religious leader and resistant Shaykh Umar Tall (1794–1864), twenty-six objects that were taken from the palace of King Behanzin (1844–1906) of Abomey when it was sacked by the French army in 1892: royal seats, portable altars, sculptures . . .

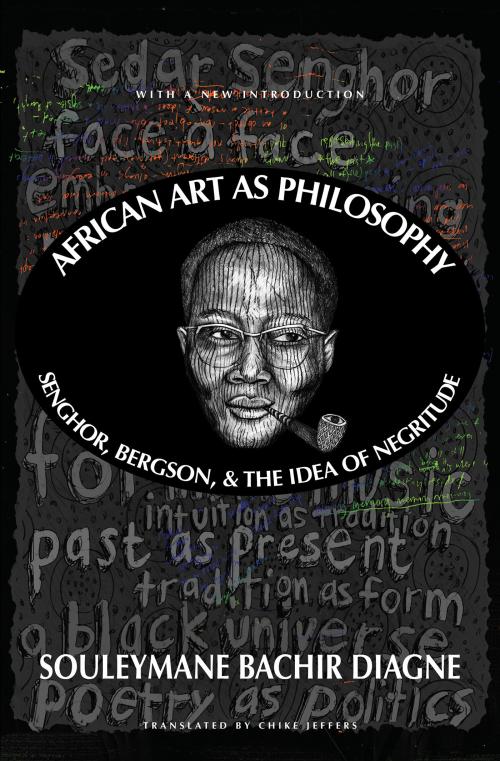

To be sure, Macron’s speech in Ouagadougou was followed by effective decisions and results, but it is necessary to recall that Africa had launched a struggle for its art in the late 1950s, a time when African nations were in the final stages of their march towards independence: the restitution of their heritage was an important dimension of their struggle. That dimension is precisely the topic of Bénédicte Savoy’s Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat, about the restitution of African art. Going through the different stages of the struggle, Savoy puts a particular emphasis on the years 1965 and 1966, when the president of Senegal, the poet and philosopher Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906–2001), was fully engaged in the preparation of the Premier Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres (First World Festival Negro Arts), which he considered to be the big event of his presidency. For him, having Dakar as the capital city of global Black arts for the duration of the festival was the true celebration of the independence of his and other African countries six years before. In this event, which brought together in Senegal more than two thousand writers, musicians and artists from continental and diasporic Africa to celebrate, Senghor saw the true meaning of the poetic, philosophical, and political movement called “Negritude,” of which he was one of the pioneers: namely, the notion that Africa was not just the cradle of the human species, but also a force of continuous creation of humanity in the continent and its diasporas. To celebrate African art was to celebrate that creative force.

The élan vital of African art in the philosophy of Léopold Sédar Senghor is the topic of this book.

How to celebrate African creative force, African artistic élan vital, when the best of its manifestations are in museums in Europe? In 1965, as the festival was being planned, in the January issue of Bingo, Paulin Joachim (1931–2012), an African poet and journalist born in Dahomey (now Benin) but who was then based in Senegal, wrote a resounding editorial, the title of which was a response to that very question: “Give us back Negro art!”* In the words of P. Joachim: “There is a battle that we must valiantly fight on all fronts in Europe and America as soon as we have found a solution for the most urgent problems gnawing at us: the battle for the recovery of our art works which are scattered across the globe.”

One word summarizes the impact of the Bingo editorial: panic. Bénédicte Savoy, who describes the editorial as a “call to arms,” writes that it had the effect of a “bomb” in European museum circles, at a time when they were eager to protect “the artistic productions of the Black world” in their possession from the consequences of decolonization. Thus, the transfer of the collection of the National Museum of African and Oceanian Arts in Paris from the Ministry of Colonies to the Ministry of Culture was meant to shield it from any claim of restitution on the principle of the inalienability of national heritage. Likewise, in Belgium, the director of the Ministry of Culture had ascertained that in the discussions between his government and the new Republic of Congo, the latter’s requests for restitution would simply be set aside. These are two examples that illustrate the defensive attitude of the museums of the North and explain the panic provoked by Joachim’s pen.

The Bingo editorial could have had a major and probably crippling impact on the World Festival of Black Arts. The museums in France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States that had agreed to lend pieces of their African collections were certainly alarmed by Joachim’s thunderous demand that “Negro art” be restituted and not just lent. It took much Senegalese diplomacy and firm commitments to put the question of restitution on the back burner for the loans to finally happen. History would repeat itself eleven years later when Nigeria organized the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, known as Festac 77.

The very logo of Festac, the famous ivory mask believed to date from the sixteenth century and representing Idia, the queen mother of the kingdom of Benin, became the eloquent symbol of British colonial plundering of African heritage. Idia is well known as one of the masterpieces of Benin court art that were looted by British troops in 1897 and kept in a collection of the British Museum since 1910. Naturally, Festac organizers asked for a loan of the “Benin bronzes,” and Idia in particular.

In an article published by the pan-African online magazine Chimurenga on 18 October 2021, under the title “Festac at 45: Idia Tales—Three Takes and a Mask,” Dominique Malaquais and Cedric Vincent recount how Nigeria was turned down for the loan of this magnificent work of art by the British Museum.

The refusal of the loan by the museum took the form of an offer to make a copy of the Idia—which was even made too late for the festival. The organizers of Festac 77 silently refused what can be described as the museum’s poisoned gift by leaving its manufactured copy in its hands. But they did more and better by commissioning the creation of another Idia by Nigerian artists. When the work was presented to President Obasanjo, he commented that it manifested the creative power that the grandchildren of the great artists of Benin had inherited from their ancestors. In other words, African classical art is creative élan vital, and not the mechanical reproduction of reality or of another artefact. This is the core of the philosophy of African art shared by Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire (1913–2008), and Léon Gontran Damas (1912–1978), the founders of the Negritude movement.

It was the message delivered by Césaire at the First World Festival of Negro Arts in 1966 in his lecture, “On African Art.” In this speech, the Martinican poet warned the artists of the continent against imitation. He declared:

In Africa, art has never been technical know-how, because it has never been a copy of reality, a copy of the object, or a copy of what we call reality. That is true of the best of modern European art, but that has always been true of African art. In the African case, the point is for man to recompose nature according to a deeply felt and lived rhythm, in order to lay on it a value and a meaning, to animate the object, to vivify it and turn it into a symbol and a metalanguage.

The message was clear: African art is not and should not be conformity to an external model, even be it African art, but must remain continuously power of creation.

To better understand the significance of the Nigerian response to the condescending offer of the British Museum, a rapprochement can be made with Walter Benjamin’s reflection published in 1935 in “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility”: that the aura that a work of art exudes in its hic et nunc presence commands a religious relationship to its uniqueness. It is precisely this uniqueness that no longer exists when photography and cinema reproduce again and again the object whose aura then inevitably declines.

To read the decision by Festac 77 organizers to recreate the Idia in the light of Césaire’s lecture “On African Art” and Benjamin’s “Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility” is to understand that their response to the British Museum’s offer was not to simply say “keep your copy, we are going to manufacture one ourselves.” What it meant was “what makes the work of art is the creative force that gives birth to it, and that matrix is continuously fertile.” First, the Nigerian Idia for the festival was not a copy but a recreation, and therefore not so much concerned with absolute fidelity to the object in the custody of the British Museum, the modern artists having moreover complemented certain aspects of it. Second, and as a consequence, it was now the “original” in the museum that had become a copy, because it has been made clear that the force that produced it had gone home, taking the aura with it. While the recreated Idia was a living object sustained by the creative power manifested by the artists of Benin, the Idia of the British Museum was now a dead copy in the glass walls that enclosed it like a coffin.

The message carried by the living Idia encapsulates Senghor’s philosophy of African art, or, rather, his understanding of African art as philosophy of élan vital developed in this book.