The publishing house looks like a ship moored in the city center, a large, pale building crowned with a roof terrace. The facade is a grid of wood and granite, and flags flutter in the wind, adorned with an ornate but resolute R. R for Rydéns.

It is on the roof terrace that the parties are held. Standing up there you feel as if you own the entire city, as if everything is lying at your feet. Slowly you are enveloped by the twilight, which creeps closer and closer as the hum of conversation grows louder and the countless fairy lights begin to glow. Young men in white shirts and black waistcoats stand behind the bar, they pour a glass of chilled white wine and place the glass on a small paper coaster bearing the same R as on the flags: gold leaf against a cream-colored background. It is said that one such coaster was found among Strindberg’s effects after his death.

The autumn party marks the real beginning of the publishing year. Anticipation fills the air, like at the start of a new school semester, and this season’s authors mingle nervously, with the hopes of the finance department weighing heavily on their shoulders.

But the spring parties are the best, those are the ones that are legendary. You stand in the endless May evening, watching the dusk slowly descend over rooftops and church spires, and everything feels like a game. It doesn’t matter if we employees have a little too much to drink, because on this occasion we don’t have to be representative and professional, we are allowed to celebrate the year that has passed, the prizes and nominations that were acknowledged only with the obligatory cake at coffee time in December because everyone was so stressed in the run-up to Christmas, the spring debuts that have gone better than we dared hope. We forget that several weeks of hard work lie ahead, with everything that has to go to print before midsummer, the final edits, the blurbs for all those back covers, the proofs, the manuscripts you fall asleep over and eventually almost know by heart, those that will generate fresh acclaim and nominations in the autumn. We help ourselves to another glass beneath the vast lavender-colored sky.

I had heard about the parties long before I started at Rydéns.

It was the spring term of 2009, a ten-week internship, and I was happy and proud to be one of the few who had secured a position with a major publisher. At the same time, I had never felt so inexperienced. The only job I’d had up to that point was as a temporary home aide and maid, I knew almost nothing about what went on in a publishing house. I had to learn every detail from scratch: what to wear, how to use the printer and the photocopier, how to integrate with colleagues, making sure to refer to them as colleagues and not coworkers or workmates. And how to navigate around the hierarchies that clearly exist, while at the same time being expected to take every opportunity to show my independence and impressive initiative.

During the first few weeks I often cried when I got home in the evenings, clutching my bundle of manuscripts.

I had just moved from student housing on Lappkärrsberget to a one-bedroom sublet in Skanstull, and I hadn’t expected to feel so lonely. When I tried to contemplate my life from the outside, it almost came across as a clichéd image of alienation in a big city—being so close to other people, yet so far away from them. I was an insignificant human being among thousands of others, one of those who dashed across Ringvägen before the light changed, who hurried down the stairs to the subway platform, pushed my way onto the first train heading north, and got off at Hötorget.

I had a nagging sense that something was missing, a low-intensity perception of insufficiency that was hard to put into words. My social circle was built entirely on chance and temporary circumstances, and would probably disappear when my studies were over. I spent most evenings at home reading, embedded in a feeling of slight listlessness. Sometimes I went for a walk down by Årstaviken, following the quayside to Danvikstull, then standing there gazing at the warmly glowing windows in Hammarby Sjöstad.

I often felt as if nothing in my life were real, or at least not as real as in the lives of my acquaintances. Somehow they seemed more rooted in the world, sure of what they wanted from their future and what they needed to do in order to achieve it. At the same time, that feeling was frustrating because, after all, I had something I could only have dreamed of a few years ago: a place to live in central Stockholm, a university education that was nearing completion, an internship with a major publishing house. Apart from the poor finances that go with being a student, and the fact that the spring was late this year, I didn’t have much to complain about.

I hardly dared open my mouth during meetings at Rydéns. Everyone else seemed so confident, defending their opinions in a polished and professional way, or taking a relaxed, almost nonchalant approach. They radiated established practice and self-assurance, neither of which I possessed. I often thought that I must say something, otherwise they would think I wasn’t interested, when in fact I wanted nothing more than to make some smart comment. But I just couldn’t come up with anything smart enough. Eventually it became a kind of obsession: so many meetings and still I had hardly said a word. If I were to speak, I imagined the others looking up, staring at me, and thinking, “Wow, she can actually talk!”

One day there were reviews of one of Rydéns’s recently published novels in almost every daily newspaper. The reception was almost universally lukewarm, just as I had expected. In fact I didn’t really understand why it had been published at all. That same afternoon I happened to find myself at the coffee machine in the lunchroom with Gunnar, the company’s editor in chief.

“Not very good reviews,” he said to make conversation, nodding in the direction of the culture sections of the morning papers that lay open on the table.

“To be honest, I didn’t think much of the book myself,” I said tentatively. This was perfectly true, but I still regretted my words as soon as I had spoken. They came across as far more critical than I had intended.

“Oh?” Gunnar replied. “Why not?”

There was no aggression in his question, no hint of wounded pride. He sounded genuinely curious.

“I just thought it was too contrived. There’s no real pain or emotion. It feels dishonest.”

“Harsh,” Gunnar said quietly.

For a moment I thought I had made a fool of myself, broken some kind of loyalty code which decreed that you must never criticize anything published by your own company. Had I ruined my chances of staying on at Rydéns after my internship?

But then he smiled at me.

“I agree. I said exactly the same thing when Jenny presented it back in the autumn, but sometimes you just have to give in. Come with me.”

He led the way along the corridor to his office, where he handed me three manuscripts with rubber bands around them.

“Read these and see if they’re worth pursuing,” he said.

“Okay . . . ?”

“They’re by first-time authors. They’ve been through an initial reading, but that doesn’t necessarily mean much. We’ll catch up on Friday morning.”

“Okay,” I said again.

It was incredibly difficult. I tried to guess what the correct opinion of the manuscripts might be, but I felt exactly like I did during the meetings at Rydéns, and during university seminars where I never knew what I was supposed to say about the texts we’d read and always wondered how it was that everyone else had so much to contribute. Where did they get it all from? I wasn’t used to expressing my views. Even though our tutors constantly stressed the importance of independent analysis and reflection, no one ever taught us these skills.

Now I didn’t even have a group to hide behind, someone else’s opinion to ride on. I read through all three manuscripts quickly, hoping that I would have an intuitive feeling for what was bad and what was good, but my brain kept forestalling me, making me doubt my own instincts. Two of the manuscripts had a clear message, and I could already picture the blurb on the back cover, empathetic phrases about highly relevant contemporary depictions giving an important perspective. I knew everyone would be on board with that description, and the novels would be regarded as both good and significant literary texts. The third manuscript was completely different: enigmatic, idiosyncratic, poetic. Compared with the other two it was unworldly, harder to explain and therefore harder to sell. My gut told me that it was the best, but I wasn’t sure how to justify my view. I was also reluctant to bear the responsibility for rejecting manuscripts that might be successfully launched by another publisher.

I became increasingly despondent as the week went on. Soon it was Thursday evening, and my computer pinged, alerting me to the group chat where a few of my fellow students had decided to go out for a drink. I left my manuscripts and went to meet them. I’d decided that I might as well give up and tell the truth when I met with Gunnar the next day: I don’t know what I think. This is too difficult for me. I guess the world of publishing isn’t my thing after all.

I had several drinks, quickly and carelessly, because I might as well get drunk now that I’d failed at my internship and lacked instinct and opinions and personality. I sat in silence on the uncomfortable seat and listened to my classmates having a boring discussion about some book on the syllabus. They sounded so infuriatingly smug, as if they were in a seminar at the university rather than three beers down among friends, they spoke as if they were trying to impress someone, yet at the same time they weren’t really saying anything, or at least nothing that meant anything.

Suddenly everything became clear to me.

I excused myself and hurried home, anxious not to lose my anger. I thought the subway was unusually slow and that the traffic lights on Ringvägen took an extra-long time to change to green. When I got back I spread out the three manuscripts in front of me, and as I quickly leafed through them again it seemed perfectly obvious: The third manuscript was the only one that was any good. It was the only one that counted as literature in the way I thought literature should be: strong-willed, courageous, written with a clear aesthetic vision.

The other two were as meaningless as my classmates’ pretentious nonsense, written in impeccable but dull prose, lying heavy and dead on every single page. The subject matter might have been convincing on paper, but they were both irredeemably boring. It was as if the authors had followed a template for significant depictions of contemporary society, which made reading them entirely pointless because you knew from the get-go what they were trying to do. Why would I want to publish something like that? Why would I recommend something that I despised? It was in fact the manuscript that at first glance had appeared to be the least relevant that was the best: It had a genuine purpose.

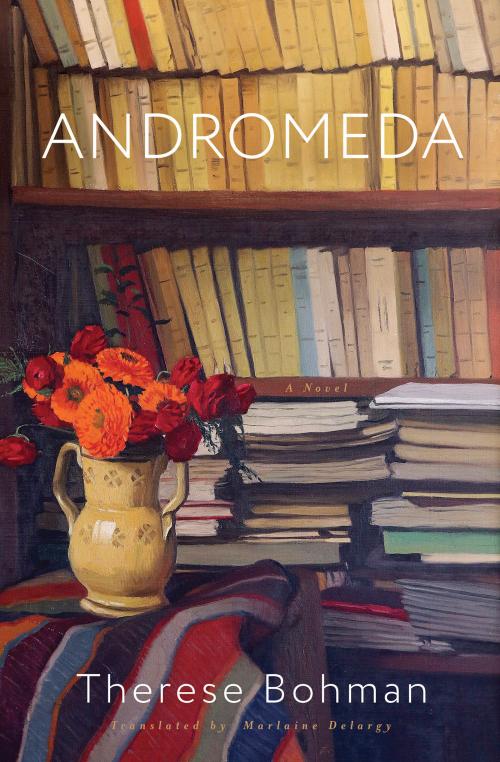

That’s exactly what I said to Gunnar when he called me into his office the following morning. I felt really important, sitting there in a 1960s leather armchair that was probably part of the building’s original decor, surrounded by his untidy bookshelves and the patchwork of paintings on the walls.

“These,” I began, pointing to the two manuscripts I didn’t like, “read as if they’ve been written according to a template for contemporary Swedish literature. If we don’t publish them I’m sure someone else will, and they might get good reviews, but to be honest I would never have finished reading them if I didn’t have to.” I pointed to the third manuscript. “This one is different. It’s something new, and it’s kind of exciting even though hardly anything happens. Like a crime novel without a crime.”

In hindsight it seems to me that I wasn’t exactly delivering original verdicts. Anyone with a little experience would presumably have said more or less the same, but in that moment I felt as if I’d been able to formulate my own opinion for the very first time.

Gunnar nodded.

“A crime novel without a crime,” he said. “We’ll use that on the back cover.”

I laughed, relieved and confused, unsure if he was joking. But he wasn’t.

“I’ll take a look at it over the weekend, but I trust your judgment,” he went on. “We have to publish a few debutants, and God knows hardly anybody can write these days. You can take care of this one if we decide to go with it.”

“Okay,” I said, still bewildered and with a whole series of objections lining up in my head—I can’t, I’m too scared, my internship will be over long before this book goes to print—but I didn’t dare say a word. Gunnar smiled his friendly but slightly impersonal smile, tossed the two rejected manuscripts into a cardboard box, and our meeting was over.