Lebanon: The Lessons of Complexity

During a stay in Beirut for a writer’s residency, a French author once declared that Lebanon condensed and summarized in itself all the problems of the modern world, and that if only one of these problems could be resolved in Lebanon, it could then serve as a model solution for the rest of the planet.

The problems this writer was referring to are certainly numerous, and cover issues such as governance, the relationship of citizens with the state, political tensions, the power of the banks, untrammeled liberalism, and the endemic corruption of the ruling classes. And in a wider sense, the writer was of course focusing on the question of multiculturalism, the mix and coexistence of religions and cultures—issues that are part of the very foundation of modern Lebanon and its government structure.

In the beginning, before it became the name of a modern nation-state, Lebanon was the name given to mountains in the eastern Mediterranean that were long celebrated in the Bible for their snow, their symbolic proximity to the divine, and especially their famed vast cedar forests. From the very beginning of the Christian era, these mountains served as a safe haven for all the religious minorities that were persecuted by the various imperial powers in the region or by other larger religious groups. The last pagans of antiquity went into hiding there until the sixth century. Then came the Monothelete Christians, called Maronites, fleeing the persecution of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire in the seventh century, then in the tenth and eleventh centuries the Shiite Muslim communities persecuted by the Sunni powers, and the sect of the Druzes persecuted by the Shiites. Much later would come the refugees fleeing countless conflicts: Armenians in 1915, White Russians from 1920 onward, Palestinians forced off their land in 1948, and finally, very recently, refugees from the wars in Syria and Iraq.

For centuries, the religious mosaic and cultural diversity thus introduced into the lands that would become Lebanon were more or less well managed by the central powers of the empires on which Lebanon and its neighbors depended. Of course, there were clashes and conflicts, but everything remained under the slightly manipulative control of the dominant powers, and notably, from the sixteenth to the beginning of the twentieth centuries, of the Ottoman Empire.

When that empire collapsed in 1918, victorious France and Great Britain divided up the Middle East. It was France that secured the mandate over Lebanon, thus fulfilling the wishes of part of its Christian population, which sought to place itself under French protection and to avoid British rule. It should be noted that the Christians had long felt closely connected to France. Many had adopted the French language and culture well before the period of the Mandate, and had dreamed of the French taking control of the country to rid them of the Ottoman occupation. This privileged relationship between the Christians of Lebanon and the French also explains why the Lebanese never felt any hostility toward France. In the Lebanese worldview, France was never seen as an occupying power, but rather as an ally. Only the highly ideological left-wing discourse of the 1970s attempted to represent France as a colonial power, which it never really was in Lebanon, despite some instances of very transient irregularities. In fact it was with the assistance of the Christians, and on their advice, that the French determined the current borders of Lebanon in 1920: they adjoined a long band of coastline and the interior plain of Beqaa to the original Lebanon Mountains, along with the northernmost part of Galilee in the south. The overriding aim was to unite as many regions as possible where the inhabitants were Christian. The Maronites, the Eastern-rite Catholics and Greek Orthodox communities actively worked toward the creation of the new nation in its present form, and considered it to have been founded for them alone, even though part of its population was Muslim or Druze. During a relatively soft Mandate that barely lasted twenty-five years, the French successfully managed the antagonisms between the various communities. But when Lebanon acquired independence in 1945, the foundations for discord were already laid, notably regarding the definition of the country’s identity. The Christians still felt closely connected to the West, the Muslims for their part felt they belonged more to the Arab world. Nevertheless, the two communities both demanded and obtained independence together, then found a way of avoiding conflict by decreeing that the new Lebanon was not a Western country, but nor did it belong to the Arab world. This was the famous affirmation of national identity by a double negative.

This peculiar identity could undoubtedly be considered as the source of all the conflicts to come, but it also proved to be Lebanon’s defining characteristic for many years: a nation straddling the great cultures of the East and the West, a crossroads, a herald of coexistence, openness, cultural exchange and integration. For the thirty years from 1945 to 1975, despite a few minor jolts, Lebanon also figured as something of an exception among its neighbors. It was the only country in the region not to fall prey to a nationalist military dictatorship, like Egypt under Nasser and Iraq or Syria under the Baath parties. It was the only democracy of the Arab world, and one of very few in what was then called the third world.

It also developed a liberal economy which has endured to this day, within a region entirely dominated by so-called socialist models—models which, in Nasser’s Egypt and in Syria and Iraq, led to disastrous nationalizations, to the disappearance of their middle classes and the impoverishment of their populations. Lebanon thus lived for thirty years in unbelievable opulence and enjoyed exceptional cultural and economic vitality.

It now seems clear that it was precisely because of the diversity of its population and the complexity of its human institutions that Lebanon avoided dictatorship and the so-called socialist models that beset the rest of the Arab world between 1950 and 1975. Religious affiliation, which in Lebanon is more cultural than strictly faith-based, underpinned all political relationships and balances. This was made manifest in the strangest political system imaginable, called “confessionalism.” All government posts were allocated approximately equally between religious communities. Every single employment position in the public sector, from the highest level in a ministry to its lowest echelons, was reserved for one or another community, depending on its presumed importance. The president of the republic had to be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and so on. This political system prevented any single community or individual from controlling the government, and averted any possibility of hegemony or coups.

All this nevertheless created something like an oligarchic system, where the political leaders were systematically elected from the most important family clans within the large religious groups. They ruled the country collegially, on the basis of elections where the focus was always on the interests of the various religious communities, rather than on political issues. And yet the social classes that divided society were strongly intercultural. A real middle class had arisen from both Muslim and Christian communities, in the face of wealthy upper classes that also recruited from various groups, just as the working classes had members from both sides of the religious divide. However, social identity and affiliation never produced true class consciousness, but were always dominated by a very strong sense of religious, cultural, and community affiliation. All this explains why the tensions between the large religious groups remained very strong, in particular because the constitution created in 1945 implicitly gave more power to the roles reserved for Christians than to those accorded to Muslims. The Muslims demanded reforms, but the Christians, fearing for their status and survival and continuing to believe that Lebanon was created for them, refused. Moreover, the Christians held great fears at the prospect of the rise in power and militarization of the Palestinian organizations that had sprung from the refugee communities in Lebanon in 1948, and that started demanding to play a role in internal Lebanese politics in 1969 and 1970. The strategy of these organizations consisted in giving their support to Lebanese Muslims. Faced with this coalition of Islamic-Palestinian interests, the Lebanese Christians took fright and armed themselves in turn, leading inevitably to the Lebanese civil war, which lasted from 1975 to 1990.

This was indeed a civil war, in that most of the fighting was between the Lebanese people themselves, but it was also very much a foreign war, because the Palestinians, Syrians, and Israelis were also involved. In 1982 the Palestinian militias were forced out of Lebanon by the Israeli invasion. But the Israelis had to evacuate the invaded Lebanese territories and confine themselves to the southern border regions adjacent to Israel. This opened Lebanon’s doors to the Syrians, who allied themselves with the Lebanese Muslims and Druzes, and with war chiefs such as the Druze Walid Jumblatt or the Shiite Nabih Berri, as well as with the Shiite Hezbollah organization, which was engaged in a war with Israel in the regions it still occupied. For their part, the Christians resisted the Syrians for years, under the command of men such as Bashir Gemayel and Samir Geagea. In 1989, the reckless and unruly Christian general Michel Aoun took it into his head to unite the Christian ranks, and threw himself into devastating wars against his rivals on the same side, notably Samir Geagea, which led to the collapse of the Christian camp in 1990 and to the entire country falling to Syrian control.

This marked the end of the civil war and the start of what is called the second Lebanese republic, which is divided into two eras. In the first, from 1990 to 2005, Syria dominated the country and its ruling class. The Muslim or Druze war chiefs, Jumblatt, Berri, along with the Hezbollah leaders, but also the less powerful Christian leaders who had pledged allegiance to the Syrians, all took over the controls. The other Christian leaders, such as Geagea and Aoun, found themselves respectively either in prison or in exile. The allocation of posts along religious lines was reinstated during this period, but with a notable difference: the dominant positions were given to Muslims and no longer to Christians.

But the main issue was that the war chiefs–turned–political leaders seized control of the government and public sector, in concert with the generals of the Syrian occupying forces, and together they developed a system of governance that was entirely based on clientelistic mafia practices. They took advantage of the huge public works program for the reconstruction of the country, and of the bountiful financial manna this generated, to shamelessly enrich themselves and to entrench corruption as a system of government and a way of life, with the culpable consent of a powerful caste of arrogant bankers. Nevertheless, this was the beginning of thirty years of renewed opulence, euphoria, creativity, and vitality, when the population shamefully closed their eyes to the actions of this noxious political class.

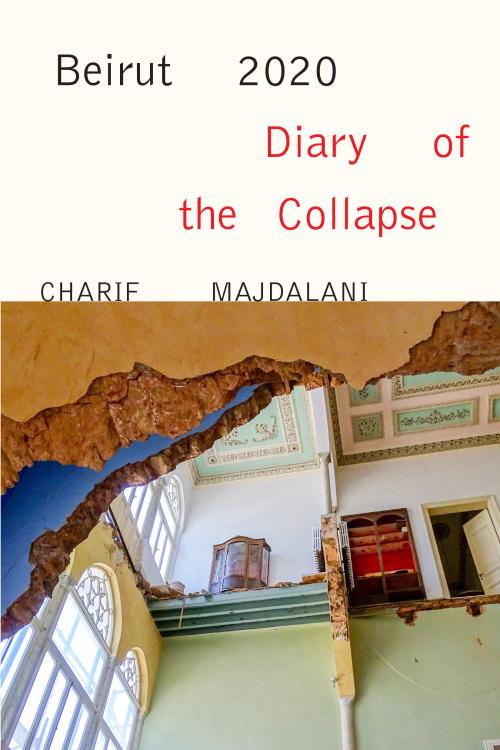

In 2005, the Sunni prime minister Rafic Hariri, the only politician who was not a former war chief and who showed himself to be extremely hostile to the Syrian control of the country, was assassinated by the Syrians with the help of Hezbollah. This sparked a huge insurrection, which forced the Syrians to withdraw. Those previously banished (Michel Aoun) or who were political prisoners (Samir Geagea) returned. But former allies of Syria, such as Berri, Jumblatt, and the Hezbollah chiefs, managed to stay in power. New alliances sprang up between them and those who had returned, which led to the persistence of the same clientelism and corruption in political practices as under the occupation. This finally brought about the collapse of the country in 2020—a disaster which the present diary documents from day to day. Despite this tormented history, Lebanon really had been, and perhaps could still be, a laboratory for some important political and social experiments. The first of these experiments is the management of multiculturalism and religious coexistence, which have endured despite violent convulsions, and lead every day to new forms of acculturation and cultural diversity. This small country has also been the laboratory where the processes of transforming family, clan, and community affiliation into a sense of citizenship are repeated on a daily basis. In other words, it is like a small-scale reenactment under a bell jar of the very genesis of any democracy.

Unfortunately these experiments have been slow to be reflected in political practice. They have suffered from being subverted or misappropriated by the ruling class, whose poor governance, corruption, and clientelization of the citizenry on the basis of community affiliation might also serve as a test case. The crisis in Lebanon in 2020 showed the dangers resulting from hyperliberal economic policies and the absence of any regulatory authority or control over the country’s social or economic life, which have turned political leaders into mafia bosses in their dealings with the nation’s citizens. The Lebanese people were forced to endure this hyperliberalism and the transformation of the public sector into a mafialike structure. They were obliged, day in and day out, to invent original forms of social and civic regulation and transaction, in the absence of any higher authority doing so. For several decades, they thought that this might also serve as a model, before they understood that a world where the banks and the super-wealthy seek to manage the life of ordinary citizens by depriving them of any official recourse to government was a complete disaster on all levels—be it social, economic, urban, or ecological. In this way as well, Lebanon’s recent history and collapse might serve as a forewarning and alarm bell for the entire planet.

1

We walked over to the olive trees, he and I. There were three of them, and some little holm oaks. On the horizon, to the east and the south, you could see mountain ridges, and in the two other directions it was so wide that you couldn’t make out the boundary of the plot. The fellow had offered me another one, with a sea view, and I had replied that I didn’t care. I can look at the sea often enough, every day at home, and if I’m going to be in the mountains I might as well gaze up at the peaks and the canopy of sky above them, with its ballet of stars at night. I don’t think he understood a word I was saying. He was strapped into a kind of vest, with a buttoned-up shirt underneath it, although it was already starting to get hot. When we got past the olive trees, walking through the dry grass that sometimes covered the remains of hardened furrows, toward a little tumbledown shack that I’d like to have rebuilt, he asked me if I could possibly pay him in cash. I burst out laughing and asked him how he thought I could get hold of dollars in cash. He didn’t comment. We had agreed on payment by check. He was just trying his luck. A few days ago, I asked Jad why landowners would ever sell their assets for cashier’s checks, and he replied that it’s usually because they have debts they need to repay as soon as possible, before the complete collapse of the pound. As for me, I want my every last penny out of the bank.

When I got home, Mariam announced that the washing machine was making a weird noise. And indeed, the noise was disturbing—a kind of regular clacking, almost rhythmical, to the beat of the rotating drum. I had actually just gotten it repaired a few days ago, the day before yesterday in fact. So I called the repairman, who didn’t answer, of course. These details of daily life which are out of our control are frustrating and make me angry. It’s easy to get angry these days.

On social media it’s always the same thing, inexhaustible, ad nauseam: economic collapse, the bankruptcy of the country, capital control, exchange rates, the pound in free fall, inflation, and penury lying in wait for us all.