Mercuro

As the plane dips toward the hinterland, she can look across at sand-colored high-rises and hills that are as dry and barren as the surface of the moon. This is not her first visit to the city. Some time ago she lived here long enough to learn something of its soul. The place is like a wild animal that has been tamed, or an ember still smoldering. You have to be on your guard, and if you sleep, you should do so with one eye permanently open. It occurs to her that the sum she was awarded as a travel grant could have been spent in Barcelona, San Sebastian, or Valencia, where closeness to the sea would have made the summer months more bearable. Then again you’re not supposed to look a gift horse in the mouth. Besides, the thing about awards is that when you get one, the award also seems to get you.

Over the loudspeaker the steward is announcing they will soon be landing and the temperature in Madrid is currently twenty-nine degrees Celsius. She fastens her seat belt, leans back in her chair, and waits with her eyes closed for the plane to grip the runway.

The two-bedroom apartment she will be living in is on calle Goya. Its rooms are lined up in a row, and the first, which could be a guest room if she ever has any guests, is followed by the kitchen, the bathroom, the living room, and, at the far end, the bedroom that will be hers. She enters the apartment carrying her suitcase and then walks around on a tour of inspection while the owner remains at the door, drumming her fingers testily against the frame. The owner tells her that the neighbors can be touchy so she’d be grateful if things don’t get too out of hand, because previous recipients of the award have held parties into the early hours. She tells her not to worry. She’s forty-five and stopped partying like that a long time ago. Once all the practical matters have been sorted, she walks over to El Corte Inglés and buys a bottle of wine. That is the first thing she does when she arrives in Spain. A lot of people go down to the beach, or to a bar or a restaurant if you are in Madrid, to unwind and absorb the atmosphere of their new surroundings; they order a mojito and jot things down in a Moleskine notebook, but she drinks wine and watches television. Glass in hand, she arranges herself among the soft cushions on the sofa. She remains like that for the rest of the evening: bloated and reclining in the steady stream of overexcited voices pouring from the news, Venezuelan series, and rowdy talk shows.

A little after midnight she is woken by a cool current of air entering through the open window. She is still clutching the wineglass in her hand, and the hard tap water she drank earlier in the evening has left the taste of old plumbing in her mouth. The buzz from the square and the pubs has got louder. She gets up, moves over to the window, and looks out onto the square. It’s down there, she thinks. Life. She decides to go out, and the nighttime pulse of Madrid starts pounding away at her once she’s on the street. She remembers what it was like when she was a student here almost twenty years ago, immersed in a daily rhythm in which you never ate dinner before ten and always went out afterward. When did we sleep? She can’t remember ever having slept in Madrid, or ever feeling tired for that matter.

She goes into a place with windows of tinted glass and furnishings in dark wood, sits at the bar, and orders a glass of cava. After a while she becomes aware of a man on the other side of the room. Several things make him stand out. He is sitting alone and keeps darting glances at the people around him; he appears to be sweating, even though the air-conditioning is going full blast and it isn’t that hot inside. She must have been watching him for just a bit too long, because his eyes suddenly stop roving and look straight at her. She looks down at the counter. She isn’t the sort of person who picks someone up in a bar, and even if she were, it wouldn’t be anyone like him. But the ball has apparently been set rolling, because the man in question gets to his feet, grabs his glass, and starts moving toward her. She realizes she won’t have time to get up and leave in a way that would seem natural before he reaches her. Once at her side, he asks her, in a voice that sounds muffled the way it can in people who don’t talk much, if he can have a seat. When she fails to respond he pulls out a chair and sits. Then he turns to her and offers his hand.

“Mercuro Cano,” he says.

She tells him her name. And that is where things stay. After a while she feels it’s time for her to find another bar, as the man has failed to say anything more. She makes an attempt to get up.

“You leaving already?” he says in response. “We haven’t even started talking.”

There is something about the incomprehension in his tone, which sounds both genuinely confused and profoundly human, that makes her sit down again. Out of the corner of her eye, she watches him extract a handkerchief from his pocket and wipe his forehead.

“Are you all right?” she asks.

“No,” he replies. “To tell you the truth, I’m not feeling well at all.”

While he says this he runs a finger under his nose as if he were wiping away lather, or the traces of some powder he had sniffed.

“I could really do with a chat,” he says. “Just to feel something in my life was normal. A little bit of normality, even if it’s only for a moment.”

Why not, she thinks. The point of this trip is to meet people as well, which isn’t going to happen if you shy away the moment someone approaches you.

“Okay,” she says.

The man nods, relieved. “What do you do?” he asks.

“I write,” she replies.

“Oh,” he says. “You write. What do you write?”

“Articles and columns for a local paper,” she tells him.

“Do you live here, in Madrid?”

“I’ve been awarded a travel grant,” she replies. “Three months with everything covered, apart from pocket money and food.”

“Congratulations,” he says.

She tells him it’s hardly worth congratulations. And if they had asked her, she would have told them she’d rather spend the grant somewhere else than in Madrid. She’s lived here before and knows that arriving any time between May and August is madness. Someone told her that in some place in the interior, it might have been Granada, the mercury had reached forty-two degrees. Sheer hell. She talks quickly, as she used to when she lived here, and is delighted to discover she can still carry that off in Spanish.

“So where do you come from?” the man asks.

“Sweden.”

He takes a swig of his drink.

“Sweden,” he says. “The man-hating country.”

“How do you mean?” she asks.

“The country you come from is supposed to be full of man-haters.”

“I don’t follow.”

“I read—” he begins, but she cuts him off with a dismissive wave of her hand.

“Look, I came out for a glass of wine and to relax,” she says. “So if you don’t mind.”

She empties her glass.

“Are you a feminist?”

“Didn’t you hear me?”

“I want to know.”

“Why?”

“To understand why you hate your men up there.”

“Frankly . . .”

“All that hate and bitterness,” he says. “Those outbursts of rage. Why?”

He looks her defiantly in the eye. She stares back. A peculiar contrast to the defiance in his eyes becomes evident when his hand starts to shake. He is still holding his glass, and she can see bits of ice jostling each other in the amber-colored liquid.

“What’s the matter?” she asks. “Why are you shaking?”

He looks down at his hand and, to judge by the way the fingers are turning white, he must be squeezing the glass against his palm with all his strength. Once the ice cubes have stopped moving, he stares vacantly ahead for so long she starts to think he has forgotten her. But just as she is about to get up and go, he looks up from his glass, grabs her around her upper arm, and says, “Sorry.”

“What for?” she asks.

“For what I just said.”

She shrugs and pulls her arm away from him.

“Do you forgive me?” he asks.

“What do you mean?” she replies.

“I don’t care. You’ll be going home any minute now and so will I and we’ll never meet again. That’s all there is to it.”

“That’s the problem right there,” he says. “Because I wish it wasn’t like that.”

“Now you’ve lost me,” she says.

“Just a moment ago it seemed like you hated me. And now it almost sounds like you’re going to say you’re in love with me.”

“In love with you?” he says with a laugh. “You’ve nothing to worry about there. I’ve only been in love with one woman my whole life and that’s my wife. Soledad Ocampo, the one and only. What I wouldn’t give to have her here beside me.”

“Oh really. So why are you chatting to a stranger instead of being with her?”

“Long story. Nothing out of the ordinary to begin with. A bit of boredom, a bit of infidelity. Same old.

Only then her illness got worse and we started going to therapy.”

“Illness?”

“She’s got a congenital heart defect.”

“Did it help?”

“What?”

“The therapy?”

“Did the therapy help?” he asks and looks at her in puzzlement. “No it didn’t. It didn’t help at all.”

“I’m sorry. Sometimes it can be a solution.”

“You don’t understand,” he says shaking his head. “This wasn’t just ordinary couples therapy; this was marriage counseling straight from hell.”

“Marriage counseling from hell?”

Her interest has been piqued. She likes listening to this sort of thing. Hearing what other people have done, how they’ve dealt with situations she has failed at, and, in a few rare instances, realizing she has dealt successfully with something others have failed at. She would like to know more, but the man is back to staring vacantly at his glass again. She senses that the conversation may have come to an end after all. She gets to her feet again.

“Goodbye,” she says. “I really hope you sort things out with your wife. Good luck.”

“Hang on,” he says, and he grabs her arm once more. “Please don’t go.”

“What is it?” she says coolly. “I need help.”

“What kind of help?”

“A roof over my head for a few days.”

“A roof over your head for a few days? In my apartment? You’ve got to be kidding?”

She can’t help laughing. He wets his lips with his tongue and wipes his forehead again.

“How about this?” he says. “So what if . . . you let me stay at yours for a few days. And I’ll tell you about the marriage counseling and the woman who ruined my life. We might as well call her the feminist. That could be interesting for someone like you.”

She’s got no idea what he means by that.

“Who is this woman,” she asks, “the one you’re calling the feminist?”

“Sor Lucia.”

“Sor Lucia? That sounds like a nun.”

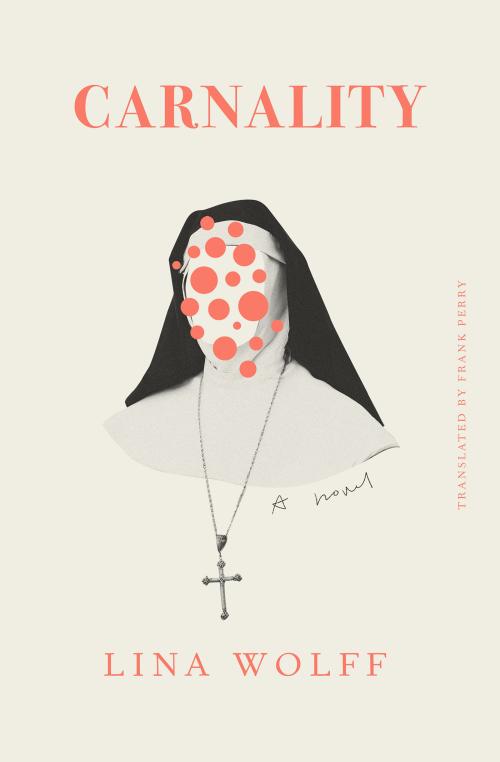

“A nun!” he exclaims. “Dead right. Imagine a cross between the strength of a Belgian Blue bull and the evil of Hitler. Throw in a couple of armfuls of hatred for men and the concentrated essence of embittered womanhood, and that’s her to a tee.”

She is attempting to picture what he just said. “Tiny and ever so slight,” he continues. “Like a

child. Only utterly ancient at the same time. Someone who’s seen it all, done it all, and knows exactly how to . . . She’s got a maimed hand as well. They say it was bitten off by a pig.”

She is staring at him. The portrait he has been painting is too bizarre for her to visualize. Though it also occurs to her that anyone who writes knows the cliché “Truth is stranger than fiction” contains a great deal of wisdom. The image of the hate-filled nun with the maimed hand is intriguing.

“Hide me,” the man implores her. “Just for a few days. You won’t regret it.”

Her spontaneous reaction is to dismiss the idea as absurd. On the other hand, an absurd idea is still an idea, and maybe she can write a column based on whatever he tells her. She says she is going to sleep on it and will let him know the following day. She gets his phone number from him. Then she goes home and falls asleep in front of the open windows in her bedroom. The night is out there. She dreams long incoherent dreams about strange men in bars and nuns in low-heeled shoes with rubber soles prowling the streets of Madrid in the hour before dawn, hunting something that never becomes clear in the dream.