the interior of paul’s car

The interior of Paul’s car is a space rather limited in volume and distributed with a certain stringency. The design of the four ergonomic seats is so precise that squeezing a fifth person into the back would be practically impossible. The front seats are separated by a short armrest half their height; it contains no storage console and provides no place to put such small objects as sunglasses or CDs.

With its leather seats, aluminum door sills, and stainless steel pedals, the vehicle’s passenger compartment expresses its owner’s intention: to possess a car that offers all available comfort and luxury, but in miniature, and for the price of an entry-level model. Paul’s smell pervades the space, assailing Ema every time she gets in the car. It’s a very woody fragrance that mingles the man’s usual cologne with his perspiration, though in more concentrated form.

After their separation, Paul will occasionally pull up next to her on the street, stop, and lower his window to say something. When he does so, inhaling that smell will suffice to unsteady the young woman for a moment, to give her the sensation of being sucked into that cockpit once again.

Almost from the start, Paul very clearly spelled out his view of their relationship. He invoked his shortage of time and his difficulties with personal availability, all owing to his family obligations. “We’ll see each other at social gatherings, but face-to-face meetings, just the two of us—those won’t happen very often.” Having already had some experience in this sort of liaison, he also warned Ema about how painful it can be for one partner to try to envision the other’s world, over which he or she has no sort of control. “Spare yourself. Don’t make comparisons, don’t compile a list of all the things we can’t do. Otherwise, you’ll run into a wall.”

Ema made a show of understanding, although she secretly hoped she could cause Paul’s thinking to evolve. She imagined being able to spend time with him far from home and their everyday lives, but since no getaway was currently feasible, she put up with brief encounters in restricted spaces, such as the interior of his car.

The car’s internal trim reflects the man. The elegance of the decorative chrome elements, the leather steering wheel cover, the hand-brake handle, and the gearshift evoke Paul’s sporty driving style. The maneuvers he makes are decisive but abrupt. No time is to be lost, no space to be wasted, and that’s why he’s chosen a compact, easy-to-drive car. Once she’s settled in her seat, Ema always feels embarked, propelled forward, with no choice but to follow the motion.

There’s something about Paul’s sudden decisions (to make a detour before dropping her off, to commandeer her for a simple errand in a neighboring town) that Ema finds ravishing, as if the car has a magical power to transport her to an as-yet-indistinct elsewhere. At such times, Ema is overwhelmed by a feeling of confidence and absolute freedom.

“Suppose we take a trip somewhere, right now, just like that?” This is what Paul seems to be on the verge of suggesting whenever his car starts to pick up a bit of speed.

However, despite promising beginnings, these flights never lead anywhere, and sooner or later, the certainty of their pointlessness ends up depressing Ema. As for Paul, he doesn’t seem to share her disappointment, contenting himself with the pleasure of rolling along in silence. Slightly irritated by what she considers his detachment, the young woman reacts by taking hold of the upper assist handle and trying to appear composed.

Paul is all the more at ease in his car because it serves as his second home. An expert in buildings and public works, he spends a great deal of time on the road, on business trips that have the added utility of allowing him to catch his breath.

If her lover knows she’s home alone, he’ll call her from his car, sometimes late in the afternoon, while driving from his swimming club to his residence. At such moments, the man sounds more relaxed than usual, having provisionally conquered an obstacle course or, more modestly, returned his focus to himself through his athletic exertions, as if he were never really available except when in motion, when leaving one point and on his way to another.

A perfect extension of his personality, the interior of his car is organized in such a way that everything is close at hand: his sunglasses, which he extracts from the glove box with a swift gesture, leaning slightly toward Ema; the seat belt comfort clip; the climate control, always running full-strength to maintain an indecently high temperature; the jacket he wears at work sites and keeps on the back seat; the safety boots in the trunk; and the short armrest, which allows his hand to pass easily back and forth between the gearshift and the young woman’s knee, provoking discomfort in Ema, as if this automatic gesture shows that she too has been consigned to the domain of handy accessories.

It was to give Ema a ride home from the labor court where they both work that Paul first welcomed her into this very personal space of his. It allowed them to become acquainted.

One day, when Paul had stopped the car and a few moments of silence ensued, Ema seized the opportunity to declare her feelings to him. He’d just informed her that he’d lost his mother. It wasn’t the first time she’d heard him speak affectionately about the brave, upright woman who raised him and his brothers and sisters on her own. Now, as Ema listened to his grief, it seemed to her that it was her own mother who had died yesterday. A barrier inside her gave way, and she felt a sudden urge to take Paul’s hand and commune with him. They had been confiding in each other for weeks, but their relationship had not yet dared to speak its name. Ema was tired of her womanish procrastinating; she felt in herself the impatience of a man. She wanted Paul to talk to her about something else. She wanted him to talk to her about love.

“You need to know that I have feelings for you,” she finally said. “And if you can’t say the same, then I think it would be preferable for us both to take a step back.”

“It’s a good thing you spoke first, because I feel it too, I feel the same attraction, and I didn’t know how to admit it,” Paul had replied.

Clearly quite disturbed, he had sat silently for a while before he spoke again, and a powerful sensation of vertigo had seized Ema; she felt like someone standing on the edge of a cliff, uncertain whether she’s going to fall.

Since that first time, when she dared to put some words in a blank space, the inside of the automobile has become an environment favorable to intimate effusions.

The sound of the car doors closing them in brings their first relief, the satisfaction of finally being at some distance from the outside world. The atmosphere changes instantaneously, as if the banging of the doors were a signal.

Nevertheless, Paul doesn’t drop his guard; he stays on the alert, inspecting the street and the pedestrians through the windows. “Our relationship must be absolutely clandestine,” he often repeats to Ema, his tone a little stern, perhaps briefly congratulating himself on the young woman’s reasonableness, a character trait he’s taken for granted ever since they first started seeing each other.

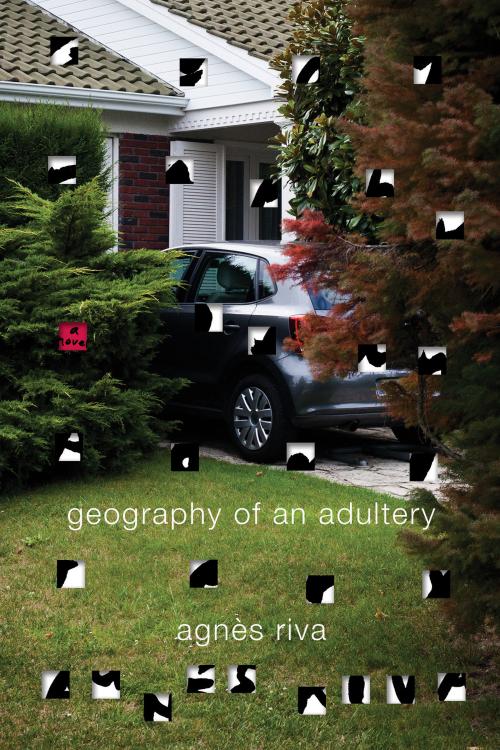

Most of the time, they park the car in town, not far from the labor court but always in an isolated spot. If they find they must settle for a place on the same street as the court, they’re careful to pick one as far away as possible, beyond the traffic circle.

Once they’ve withdrawn into the shadows, they can observe the scene at a distance—the members of the court exchanging a few words before they disperse, the neighborhood emptying out as dusk comes down. The positions they retreat to offer a different perspective on the social game and lessen a little the usual pressure to play it, especially as far as Ema’s concerned, for as a general rule she’s eager to get to gathering places, as if she were always afraid of missing an opportunity to connect with other people.

After they break up, this distance will be what the young woman misses most, what makes her fearful of having to experience events up close again.

The time constraints, the confined, narrow space inside the car, and their side-by-side (as opposed to face-to-face) position—all these factors encourage the couple to talk more freely. The car is the only place where Paul uses the word we.

Sometimes, when they’ve begun an important discussion and a meeting’s about to start, they stay in the car, waiting until the last possible moment to spring out and rejoin the others. They speak to each other with such freedom that Paul is surprised and says so out loud. For example, on the day when Ema, blushing with emotion, made an effort to reveal to him the depth of the solitude in her that her marriage had not availed to fill.

“You’re like an iceberg,” Paul had said, teasing her. “The part of your personality that people can see is only what’s above the surface. Underneath, you’re a confused mass of affects and emotions that complicate your life.”

This ease of intellectual exchange fosters Ema’s fantasy of an ideal amorous space where everything can be said and understood, and it simultaneously awakens a physical desire that leaves her feeling unsatisfied when the time comes for them to part.

Because of the car’s untinted windows and the ubiquitous streetlights whose bright halos illuminate its interior, Paul’s and Ema’s gestures remain constrained. They can allow themselves some discreet movements—they squeeze each other’s hands in the darkness of the car, under the armrest, or Paul furtively strokes the back part of Ema’s cheek—but embraces and kisses are not permitted until they’re out of town. And even then, the man’s attitude retains a certain stiffness; he has a way of casting off his seat belt expansively and then making an awkward three-quarters pivot toward the young woman.

The occurrence of these privileged moments is completely dependent on Paul’s convenience, on whether he passes and picks her up or she’s obliged to make the drive by herself, at the wheel of her own car, and whether he takes her straight home or decides to postpone for a little while the moment of their parting. Ema thus finds herself subordinate to the imperatives of his schedule.

As the weeks go by, Ema realizes that Paul is capable of going for days without showing her any sign of life. When such an absence grows too long for the young woman, who knows they can’t speak freely on the telephone, the inside of the car allows her to reclaim him: “What’s going on?” “Where were you?” “Can’t you at least try to keep in touch?” “Yes, you were worried, I understand,” “I didn’t notice the time passing,” “I promise to pay more attention in the future,” Paul answers at once.

Angry at first, Ema ends up murmuring to him, sweetly and affectionately, what she expects of him, namely that they will meet in a more intimate space, in a Paris restaurant, for example. But when no concrete response is forthcoming and the young woman starts to doubt, all Paul has to do is to seize her hand and look deep into her eyes and say sweet things to her, and they both instantly feel the spark again, and their attachment, the strength of their bond, appears obvious to Ema.