Introduction

On 15 september 1983, I had a dentist’s appointment. My family had been going to the same man to fix our teeth since childhood and he believed, for reasons I can no longer remember, that anaesthetic should be avoided whenever possible. Random moments from that Thursday morning have stayed with me: the walk home along our local high road, the dappled light of early autumn, feeling hopeful about life and realising I need never go back to the same dentist. And then I arrived home and opened the front door for the last time that things were just about okay.

My mum was sitting at the kitchen table, looking at me as if she was horrified I had come home. “He doesn’t know yet,” she said, and it took a moment to realise she wasn’t talking to me. She was talking about me. I was the one who didn’t know. In the same instant, I noticed the shadow of a policeman’s uniform in the background.

The policeman was very young, and seemed at a loss over how to behave in front of a distraught woman. Coming to our house must have been one of his first jobs, my mum said, recalling the agony of the occasion years later. It seemed unfair to everyone. He was not nearly old enough for his task: to tell this woman that Robert Borger, her husband and father of her four children, had been found dead that day.

Our dad had taken his life with whisky and painkillers in a lonely room away from home. I only recently found out the mundane details. He had stolen the pills from my grandma’s bedroom. Annie McCulloch, a tiny woman who loved butterscotch sweets, ginger wine and the Queen, had lived with us almost all my life and had died just three months earlier from respiratory complications caused by her modest smoking habit and reliance on coal fires. He must have gone into her room after her body had been removed and taken her prescription tablets. They were called Distalgesic, a brand name for a combination drug which featured in so many suicides it was withdrawn from the UK market twenty years after our dad made such effective use of it.

He had been missing for about a week before his body was found. Our mum, Wyn, had told him she could no longer put up with his behaviour: his moodiness, starting each day with a groan, and the inescapable fact that he had maintained a relationship with another woman despite repeated promises to stop. Mum had said she had had enough. He asked if that was her final word. She said it was and he walked out of the house. Some hours later she gathered me, my elder sister Charlotte and two younger brothers Hugo and Bias (our abbreviation of Tobias) in the kitchen to try to imagine where he might be. We probably did not treat the task with its proper urgency, but then we did not know what she knew: he had gone missing ten years earlier, calling home on an icy Christmas morning to tell her he had taken an overdose and was in a telephone box near Uxbridge. She called 999, but there was some difficulty getting an ambulance sent, as it was the height of the turmoil of Ted Heath’s government and the hospital ancillary workers were striking.

Wyn left us at home with Grandma and went off looking for him, eventually following his trail to a hospital ward. She got him home, put Christmas dinner on the table and the next day took us out for a walk in the park with friends. Nothing more was ever said about the episode.

This time, there had been no call from a phone box, and she had to try to restrain her growing panic in front of us. My sister Charlotte and I were assigned people to call to enquire whether they had by any chance seen our father. We sat around the kitchen table and tried to think up new possibilities, and none of us came up with the right answer, despite the trail he had laid for us.

Some months earlier, he informed us that he had joined the National Liberal Club in Whitehall, an announcement we had greeted with astonishment and derision. He took our mum to see it and all she could think of was how dreary and stuffy it was. It seemed an absurdly grand and unnecessary thing to do. Members were allowed to stay in its rooms for a reasonable price, but he lived in London, so what was the point?

It had cost money up front that we could hardly afford. I found it funny and irritating without properly considering how sad it was. In retrospect, it was probably part of the staging for his suicide, and no doubt he felt it had a ring to it – “he died at his club.” He was trying to depart the world as “a man of substance” at a time when he felt at his most insubstantial.

After more than two decades lecturing in psychology at Brunel University, he had seemed likely to inherit the chair and finally become a professor, a position that must have seemed preordained in his teenage years when he shocked everyone with his precocious academic achievements. At the last moment, however, he was passed over and Brunel chose a younger psychologist from another university who had written popularly accessible books and frequently appeared on television.

My father had told me he blamed himself for mentioning this man’s name to someone in the university administration, and wondered whether, if he had kept his mouth shut, they might have forgotten to ask this outsider to apply. He sank into gloom.

I was twenty-two at that time. I had left university and was working at an adventure playground in Fulham for the summer. One sunny day he turned up unannounced and sat at a picnic table watching the kids on the climbing frames. I did not know what to make of it, as I had never known this methodical man to spring surprises. Most evenings, I would go to his study, and he would set aside his work and we would play chess on a makeshift desk he had fashioned from a sheet of plywood and a single metal leg on a hinge that balanced on the armrests of his chair. He was far from emotionally expressive, and to the extent that we had a bond, it was forged in these games: the careful placing of chess pieces and occasional comments on the wisdom or otherwise of the move.

Turning up in Fulham that day, he seemed to have shrunk. We sat and talked for a while at a picnic table but about nothing of consequence. All the questions I had for him would only come to me much later.

In his suicide note he left for us four children, he said he could not see another “tolerable way out,” and that he was sure it would be better for us in the long run to have a dead father than a “lonely and depressed old man.”

I kept the note, in his neat, even handwriting, in a file of old documents, where it remained unopened for decades. I had to force myself to read it again, so I could write this chapter. “To be pathetic is the ultimate sin,” he wrote. It is a line that to this day sets my mind racing to list all the sins that are so very much worse. He wondered if he had loved us in the wrong way and whether he had tried to compensate for his own shortcomings through us, a reference to his ceaseless

goading over academic achievement.

“Apart from that, there is no moral,” he said.

There were other envelopes he left behind, including a separate note for our mother, which was pointed and recriminatory. There were bank statements underlining our precarious financial state. There were no savings.

A few envelopes were addressed to him but had remained unopened. Inside, my mum found pictures of a small fair-haired boy. We had a half-brother. His name was Alex, and Robert had refused to have anything to do with him, cutting off relations with Alex’s mother, the woman with whom he had had an affair for more than a decade, after she had insisted on having the child. It still astonishes me that our mum continued to function at all, but she called us together, and insisted we meet Alex who, she pointed out, bore no blame for the collapse of our world. So not long afterwards, we picked him up from his mother’s flat and took him to London Zoo. He was a self-assured four-year-old with very clear views on what he wanted to do and what animals he wished to see. We, his four half siblings, were willing to be guided by him, wandering around the cages and enclosures staring at the animals, uneasy and overwhelmed by the sheer weight of all the things we had just discovered.

My brothers and sister spent the weeks following our dad’s suicide struggling with the impossible task of comforting our mum and thinking up ways to distract her. At one point, Bias rowed her in circles around the Serpentine in Hyde Park.

I was going around town doing the practical things, relieved to be out of the house. The bureaucracy of untimely death kept me moving, filling forms and answering questions.

Besides the suitcase of clothes and formalities at the club, there was a car to be extricated from the police pound, and a body to identify. I volunteered to do all of it.

Westminster Public Mortuary on Horseferry Road is round the corner from the Houses of Parliament. As I remember it, you had to go up some stairs to a sort of gallery where there was a long thin window. I was asked if I was ready and a curtain on the far side was pulled back, and there he was lying on a gurney some three metres away, obviously him but at the same time utterly unrecognisable with all life extinguished.

I was numbed by the experience but later thought I had been luckier than my siblings. It is surely better to see the dead one last time, before they disappear forever.

The next job was to pick up his suitcase from the Liberal Club, where I was met by the housekeeper who had found him. She was a short woman with a Spanish or Portuguese accent. She took me to the room in which he had died and on the way up in the vintage wooden lift, she began to cry. Fumbling for something to say, I could only apologise.

The hardest task was making calls to family and friends to tell them the news. My sister and I had our own lists. I still have a vivid mental image of the piece of paper with scrawled names lying on the blue carpet by the phone. With each call, I was afraid people would ask what had driven my father to abandon us all, but no one did.

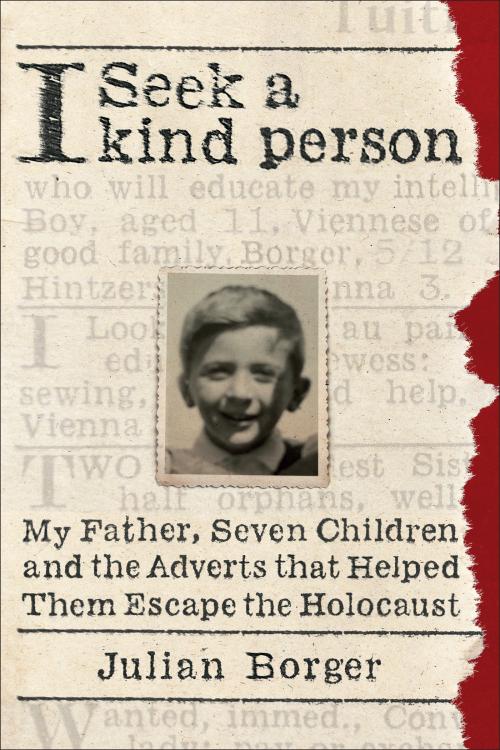

The call I left until last was Nancy Bingley, whom we all knew as Nans, the Welsh foster mother who had brought my father along the journey from boy to man, from when he first arrived as a Jewish refugee from Nazi Austria. She had been a kind, calm, grandmotherly presence in our lives.

Nans answered the phone, as people did in those days, by reciting her number, and I delivered my prepared script. On the other end of the line, there was an intake of breath, a pause and then Nans said firmly: “Robert was the Nazis’ last victim. They got to him in the end.”