THREE MONTHS BEFORE THE OPENING OF THE BRUSSELS WORLD’S FAIR EXPO 58

Everywhere you look, in color or black-and-white, there he is, on the right side of the photo. Each time the commissioner-general of Expo 58, Baron Guido Martens De Neuberg, needed his velvety voice, his athletic silhouette, and his sparkling white smile, Robert Dumont had stepped up. No matter the time, place, or subject.

Robert Dumont: so efficient, always true to his word. To say this Walloon was the personification of fidelity was something of an understatement. To quote Baron De Neuberg, who praised his many talents in the art of clearing land mines, “He was always a length ahead, focused on achieving the impossible.” Recognized as one of Belgium’s most influential bankers, Robert was both exuberant and extremely private, calm, cool, and collected—the exact opposite of his friend Guido. A man as impeccably dressed in the city as in the countryside of the Ardennes where he retreated to escape from the frenzied pace of the capital, he was, in the eyes of Baron Guido Martens De Neuberg, one of those guardian angels the heavens send to simplify the lives of the elect.

As he approached fifty, he would have liked to preserve the reputation he’d so carefully constructed, sometimes following in the footsteps of the mighty, at others keeping as far as possible from the centers of power. But now entrusted with the most delicate portfolio inherited by the newly elected social-liberal government, where his friend counted as many allies as adversaries, Robert had seen dark clouds gathering on the horizon. Catapulted into the position of subcommissioner of the World’s Fair by Baron De Neuberg, he’d drawn up a list of the dangers ahead. As he raced along the obstacle course that had become the committee’s daily routine, there was just one thought—a haunting premonition, really—that he could not shake. The pressure on the team he and the commissioner-general formed would only continue to mount, and soon it would be unbearable.

Yet he knew how to choose his battles—he was not the sort to take up Sisyphus’s challenge without having first measured the boulder’s weight.

Still, with the first wave of articles railing against “De Neuberg’s style,” and decrying how, “by playing the ostrich, the baron risked delivering Belgium a stinging failure,” his doubts crystallized. He ought to have trusted his instincts, listened from the start to the voice whispering that the success of the World’s Fair was a deeply personal matter for the commissioner-general. The mother of all the battles that the man, his friend for more than thirty years, continuously waged against his internal demons. Battles to which he’d sacrificed his time, sleep, and energy—that was clear to everyone who rubbed elbows with the baron, whether in his private residence in Uccle or in the villa in Belvédère that the Royal Foundation had put at his disposal for the duration of the fair.

Robert was one of the few who knew that this global rendezvous would be the final curtain call before Guido Martens De Neuberg retired from the public stage. The man who was so happy to play the lead wanted Expo 58 to be like a fireworks display, lighting up the sky before he turned the page and began his next act far from the footlights, as a collector and dealer specializing in primitive art. “Who knows, my dear Robert,” he’d confided, “maybe I’ll open a gallery on the shores of the Thames, as my colleague there in our Congo keeps suggesting, in telegram after telegram. But if you ask me how I imagine my grand finale, the last act of my long march beneath the tricolored flag, I can only say that it will be unforgettable. I intend to give all Belgians something to remember, and then bow out. There’s only one thing spurring me on: finally getting to enjoy the peace and calm of anonymity.”

As January stretched on, Robert Dumont was more and more convinced that, if the former judge at the head of the organizing committee refused an all-out battle against his many detractors, it was simply because the “great coup” had become his sole focus in life. A grand finale that the kingdom would applaud when the curtain fell on the biggest event the world had seen since the end of the Second World War.

De Neuberg was betting that on that day, he’d stare down not only those skeptics fretting about national prestige but certain former rivals, passed over by the king, who used journalists to ambush him indirectly. That moment when he would prove to his father, who’d turned his back on him when he was just a baby, wailing in a cradle, that a lucky star had taken the place of the man who ought to have been the sun of his life and led him to this consecration.

There in his American exile, the elder Martens would learn that the abandoned son had burnished the only inheritance he’d left him—a patronym that once echoed through the courtrooms of the Palace of Justice in Brussels—to a shine that would make any scion of a good family pale with envy. When Brussels was decked out in all its finery, Belgium’s favorite son would restore to the kingdom the honor and prestige it had lost in the eyes of the civilized world after the humiliation of the Nazi occupation. That—the commissioner-general predicted between two shots of cognac—would be the first step on the long path that would one day lead to their reconciliation. And for that long-deferred reconciliation, he would set the conditions.

Nothing was less certain, Robert thought.

Because they were totally unaware of the mad hope that lived buried deep in Guido Martens De Neuberg—unaware of the flame that had consumed him since his youngest days—the women and men who crossed his path saw only one side of the mountain, the side where he basked in the glow of his own self-assurance: “Baron Narcissus,” that was the nick-name bestowed by the French press and which his friend so often trotted out to tease him.

The subcommissioner was keenly aware that by asking for his services, the baron had demonstrated both lucidity and realism. Time had allowed them both to take measure of a loyalty matched only by the confidence they had in each other. Having followed closely Robert’s brilliant career in the world of finance, Guido had seen for himself the many talents of the bow-tied banker, as he was known to his fellows. Negotiations and communications were not the least among them.

Beneath the coffered ceilings of the royal palace, the euphoria that had welcomed the announcement in November 1953 that Belgium would host the prestigious event had given way to gloom.

That morning, before a gathering of counselors in the sumptuous Salon du Vase, the grand marshal of the royal court made no attempt to hide his exasperation: “We will not be ready! De Neuberg is playing the king for a fool, and you can be sure I intend to put an end to that. I expect clear explanations from him—no more of that double-talk his alter ego feeds reporters at each of his press conferences.” The power behind the throne was irritated by a series of reports insinuating that work on the fairgrounds was seriously behind schedule. And if that weren’t bad enough, the national press was unanimous in asserting that France, with its eighty-meter-long arrow atop the pavillion designed by the architect Guillaume Gillet, was set to upstage the host country.

No one sitting at that table thought it wise to recall that for five years a series of governments had, one after the other, proclaimed the Atomium in Brussels the eighth wonder of the world, much to the delight of King Baudouin and Queen Fabiola, who could barely contain their enthusiasm.

The grand marshal of the court was stewing in anger. He hoped to muster arguments sufficient to convince the head of state, who in turn would easily make Prime Minister Achille Van Acker see that the executive branch had bet on the wrong horse. Guido Martens De Neuberg, the man from Limburg whom the kingdom had entrusted with the mission of making Heysel, north of the capital, the center of the world, was simply not the genius they’d imagined. Far too many signs led to the conclusion that the baron needed a captain capable of leading Expo 58 safely to port. If De Neuberg couldn’t live up to the responsibility the palace had placed on him, then he needed to be shown the door. Three months ahead of the official opening, there was no more time to waste.

To say that the commissioner-general detested the grand marshal of the royal court would be another understatement. Guido Martens De Neuberg ignored the invitation to come to the palace and instead sent his adjutant to cross swords with King Baudouin’s inner circle.

A methodical man, Robert Dumont knew it was time to get a handle on what was quickly becoming a festering crisis. He warned the baron against taking aim at the wrong target. The king’s senior adviser was acting within the scope of his duties to keep the chief of state informed. Once again, because they had little to feed the public, journalists and commentators had taken on the role of Cassandra, crying wolf in order to provoke a reaction and learn the truth. If they couldn’t convince the press, they needed to seduce them. And seduction is a tango, a highly choreographed dance for two. Clearly there were delays, but it was quite a leap from that to the suggestion that the house was on fire—yet, sadly, there was no shortage of misinformation circulating. His first mission was to reassure everyone. Words mattered, but so did style. He would take charge of it personally and ensure a strict control of communication channels.

His eyes brimming with optimism, but without even a hint of obsequiousness, he would let it be known who was at the plane’s controls. The journalists were just doing their duty and the committee, while remaining steadfastly focused on their assigned task, only wanted to make things easier for them. Feeding into reports and editorials circulated by the foreign press about the looming catastrophe did nothing to reassure the Belgian public. The few bungles noted here and there in no way justified fiery predictions of a national humiliation. Belgium had lived through worse.

You had the subcommissioner’s word on it.

They were in the midst of that attempt at reconciliation when, in his spacious office in the villa in Belvédère, Commissioner-General De Neuberg gave in to one of those impulses so typical of him. Impulses which, all too often, short-circuited the efforts of the communication virtuoso who struggled week after week to protect the impetuous baron from himself. “I understand, I understand what you’re saying, Robert. Still, I am far more determined to see the icing put on this cake on the evening of October 19 than is that lackey dressed in his Sunday best who has done nothing more than play the role of inspector without ever leaving the palace. You know what? You’re going to go see him and let him know in no uncertain terms that we are not a ragtag bunch of incompetents. And if Mister Grand Marshal of My Latrines treats you badly, you just turn and head back to headquarters. Then it will be I, Guido Martens De Neuberg, ennobled because I stood up to the Wehrmacht during the two hundred and six days of my captivity, who speaks to the king himself. Enough is enough!”

The ailment eating away at the baron had nothing to do with anger. Nor with self-assurance. It was something much more banal: The man wanted to be loved. Yet Robert doubted that all the love Belgium might offer would be enough to assuage his friend who, after a meteoric career in the courts, had exchanged, much to everyone’s surprise, a judge’s robes for a military uniform and then taken on a series of ministerial portfolios after the liberation. As far as Robert could tell, the ailment had one and only one face: the father effaced by four decades of silence, the one he’d nick-named “the great deserter.”

No, the commissioner-general would not go to the palace.

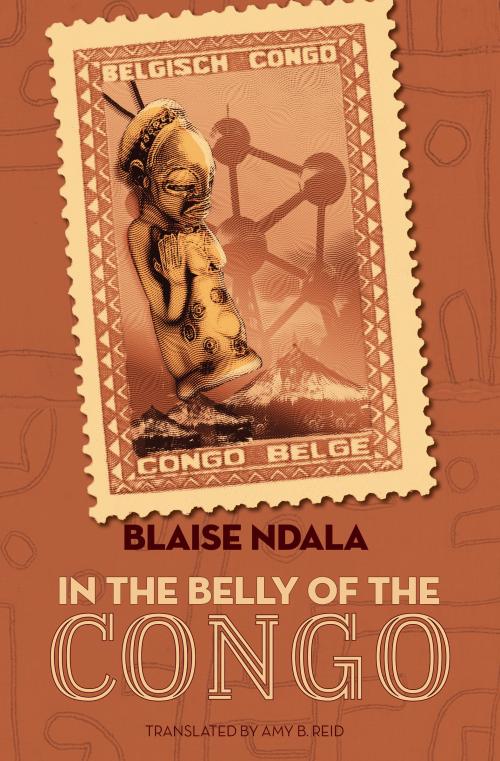

“Should I come up with some excuse to mollify him? He’s just out to thwart our plans. If he wants a fight, he’ll get it. Now is the time—no two ways about it. I’ll leave it to you to go, and I’ll focus on what my associate there in his villa in Léopoldville has to say. Between two visits to the worksite, I need to decide what we should take care of first, securing the masks in rare wood from Kasaï or the brass statues from Katanga. My word! I’d be running one of the largest galleries in London if I could tell a Pygmy arrow from the scepter of a Lunda king—Lunda, Kuba, or who knows what Congolese tribe! Ah, those great lords of the tropics! Anyway, I’m off on a tangent, Robert, a tangent. I’ll let you head to the palace. You’ll know how to handle it . . . Just like always.”