Salon.com 2004 Writing in the Margins, Scott Thill

Speaking of unhealthy delusions, the 9/11 hearings were a bracing primer on the ways reality can rear its ugly head and disrupt the best-laid plans of postmodern America, a place where sound bites, confusion and capitalism casually trump material evidence on a sometimes daily basis. That mechanism of delusion, whatever its form, has continually fascinated thinkers and doers everywhere, although the French seem particularly taken with it. Shortly after the first Gulf War, the notorious Jean Baudrillard — a guy who takes particular glee in pushing buttons and punching holes in reality — wrote an audacious book called "The Gulf War Did Not Take Place," which categorized Bush 41’s cowboy excursion to save Kuwait as a bloodless media event. That piece of Swiftian scholarship cost him dearly, but his penetrating insights about media and war (and media war, to be specific) seem like prophecy today, as the American military wades through a similar quagmire in the same damn country.

While Baudrillard’s work often touched every base in the stadium, French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s output seemed to stick most capably to film studies. For a time there in the ’60s and ’70s, if you were studying film, most likely you were doing it through Lacan’s prism, because his theories of the self involved a subject struggling to distinguish its own desires from the real world. What made Lacan cool was the fact that he realized that human beings constructed fantasies they convinced themselves were reality, while the material world they occupied resided far outside of their constructions. He might have partially agreed with the popular advertising slogan — "Perception is reality" — because so much of his work is built upon misrecognition.

Or maybe it’s that way because, as author Todd McGowan explains, Lacan fully understood how tangled the knot of desire and confusion can become, especially in cinema. "The focus of Lacanian theory on the operations of desire and fantasy make it invaluable for film criticism," McGowan says. "Lacan orients psychoanalysis around the desire of the subject, and he relates all questions — ethical, religious, aesthetic — back to this desire. Cinema is also organized around the desire of the subject. As spectators, we choose the films we see because of the way that they promise to mobilize our desire. Lacan understands that this desire is always unconscious — so that we don’t know why we desire what we desire. So Lacanian theory allows us to interpret films in a way that uncovers their unconscious appeal, not just their conscious appeal."

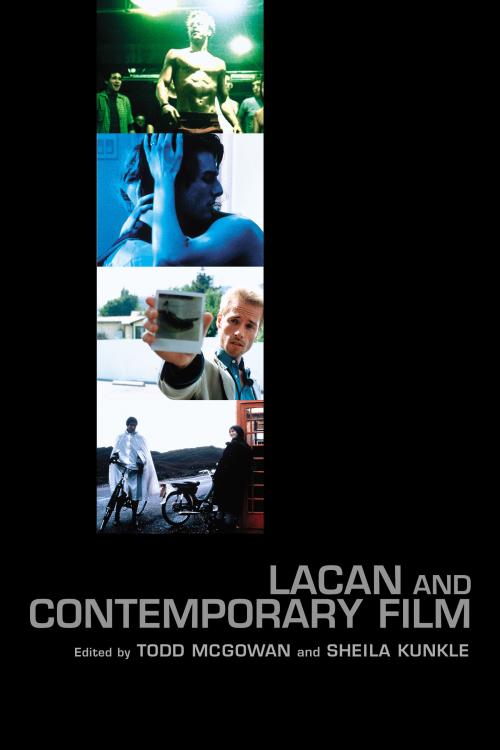

McGowan and Kunkle’s book is doing its best to reclaim film studies for Lacaniacs, and that is a good thing, because film culture is filled to the breaking point with characters continually misrecognizing their personal fantasies for reality. Almost everything Kubrick and Hitchcock made comes to mind (although the latter was partial to Freud), as well as most of film noir and the cinema of Charlie Chaplin. But "Lacan and Contemporary Film," as its title suggests, slaps scores of more recent films — "Pi," "Memento," "Holy Smoke," "Breaking the Waves," "Eyes Wide Shut" and many more — beneath Lacan’s microscope to see what pops up.

Even better, these essays keep the jargon to a minimum; the excellent Slavoj Zizek (who helped explode Lacanian film study with "Enjoy Your Symptom: Jacques Lacan in Hollywood and Out") dives right into his critique with barely any setup at all. "Lacan’s theories are notoriously — and even intentionally — difficult," McGowan added. "All of our contributors, however, are fully committed to presenting Lacan’s thought in an accessible manner. This is one reason why each of them has been drawn to the analysis of film. Film allows us to see Lacan’s theories in action, to transcend the difficulties of terminology that haunt many readers."

The result is a collection of brainy film essays that make Michael Medved look like a hack (well, like the hack he is).