INTRODUCTION

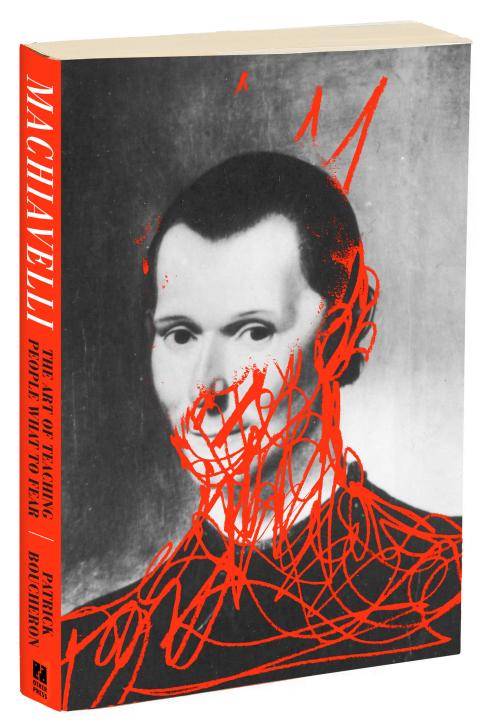

THE ART OF TEACHING PEOPLE WHAT TO FEAR

“REAL POWER IS — I don’t even want to use the word — fear.” This sentence could have been written by Niccolò Machiavelli. It was spoken by Donald Trump in March 2016 when Trump was still only a candidate for the U.S. presidency, and these words now appear as the epigraph to Bob Woodward’s book Fear: Trump in the White House. Is a more off-putting introduction to our subject imaginable? If we are tempted to assign words spoken by Donald Trump to Machiavelli, it’s not just because many Western leaders have, and for a long time, bolstered their sense of their own power by affecting a cynical and crafty tone in the belief that it represents the last word in Machiavellian thought. It’s because we literally don’t know what to think of Machiavelli. Should we admire him or not, is he with us or against us, and is he still our contemporary or is what he says ancient history? This little book doesn’t pretend to resolve these questions; nor is it addressed to those who will read it to feel that they have right on their side — whether that side is answerable to justice or to power. On the contrary, this book tries to stay in that uncomfortable zone of thought that sees its own indeterminacy as the very locus of politics.

I should, at this stage, give a few explanations about this book — who is speaking, and to whom. I don’t consider myself a historian of political ideas, but I approached Machiavelli a decade ago, yoking him with Leonardo da Vinci in an essay on contemporaneousness. Unexpectedly, I found Machiavelli a useful guide and support — I’d almost say a faithful friend, one whose intelligence never failed me. This might seem overly sentimental if it didn’t echo Machiavelli’s own image of discoursing with the ancient Greeks, as he put it in his famous letter to Francesco Vettori in 1513, where he describes writing The Prince: “I am not ashamed to converse with them and ask them for the reasons for their actions. And they in their full humanity answer me.”

My conversations with Machiavelli became more regular and fruitful as I approached topics of which the Florentine author was, in his day, the most clear-sighted analyst. This happened first as I researched the political meaning of the architecture of the quattrocento. Machiavelli taught me to see it less as a representation of power than as a machine for producing political emotions: persuasion, in the public buildings of the republican city-states; and intimidation, in the fortified stongholds that the princes built to keep those states in line. It happened again when I was trying to understand how the political instability of Renaissance Italy, riven with conspiracies and coups d’état, represented a structural element of princely power, which inevitably uses violence as the foundation of law. In every case, Machiavelli proved a worthy brother-in-arms who, because he had thrown light on his own times, threw light on ours — proving himself a contemporary in the very best sense.

During the summer of 2016, I gave a series of daily talks on French public radio in which I tried to articulate this capacity of Machiavellian thought to sharpen our understanding of the present. This little book collects those texts, which in their biting brevity and direct address attempt to harmonize in style with Machiavelli — not simply his manner of writing but his art of thinking, which brings to a flash point the fusion of poetry and politics.

Only one of these talks was not broadcast on the France Inter network during the summer of 2016, the fifth, focused on Machiavelli’s reading of Lucretius’s De natura rerum, “a dangerous and deviant book that makes the world jump its rails and come off its hinges.” The plan was to air the episode on Friday, July 15, but it was swallowed up by the sorrow, anger, and numbness that followed the terrorist attack on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice on July 14, France’s national holiday, when eighty-six people were killed and more than four hundred wounded. Although this book restores the text to its original place, there is still a gap left by the lasting stamp of fear.

Is that why I have chosen to give prominence in the book’s American edition to the politics of fear? Not solely. As I write this preface, I am remembering a dialogue that I had with the political scientist Corey Robin, the author of a major book in 2004, Fear: The History of a Political Idea. “One day,” he wrote, “the war on terrorism will come to an end. All wars do. And when it does, we will find ourselves still living in fear: not of terrorism or radical Islam, but of the domestic rulers that fear has left behind.” Our discussion, which led to the publication in 2015 of L’exercice de la peur: usages politiques d’une émotion (Spreading fear: the political uses of an emotion), asked whether the American way of fear might be exported around the world. We touched on Hobbes, of course, de Tocqueville and Hannah Arendt, but also Machiavelli, who continually inquired about the fears of those who govern: What makes them truly afraid? When justice stops being effective (or when crimes of corruption stop being punished) and when political violence is no longer a threat, there is nothing left to cause fear in those who govern shamelessly, that is, buoyed by a mood they aren’t in control of and that no one is on hand to countervail. What will then happen to the republic? This question inevitably arises when anxiety is felt about democracy, because the republic loses its stability when it no longer reflects a pacified equilibrium between the different fears that divide it.

In 1975, J. G. A. Pocock defined that loss of equilibrium as “the Machiavellian moment,” when there is daylight between a republic and its values. American historians have since associated Machiavelli’s name with that form of political crisis, a practice I have followed in this book. And today we are undeniably living through another Machiavellian moment, again bringing the Florentine author close to the core of American reality. But the author of the present lines is in no position to analyze the ins and outs of the situation, other than by this cross-Atlantic dialogue. What is fundamentally at stake is the capacity of the available political language to make sense of current developments.

Living in unstable times, Machiavelli was keenly aware that the old political lexicon, which the Middle Ages had inherited from Aristotle, no longer served him adequately. One instance was the basic opposition between the ideas of reigning and dominating, which lay at the heart of the medieval concept of government (the regimen). By describing the exercise of power as a skilled technique of domination, Machiavelli showed that the old political language, founded on key distinctions, was out of date. And Machiavelli defined the intellectual’s task as a kind of resoluteness toward truth — being unmoved by the dazzle of words to “go straight toward the actual truth of the matter” (andare drieto alla verità effetuale della cosa). This experience, which is profoundly Machiavellian in nature, is one that recurs again and again in history, whenever the words for expressing the things of politics become obsolete. What do we do when confronting adversaries we can’t put a name to? We call them “fascists,” for want of a better term — just as in Italy’s medieval communes, the people called the lords “tyrants.” We intend to confound them, to abash and bring them down, when we should in fact be examining what they say closely for its fascist potential. One thing is certain: when we use words from the past, we are showing our inability to understand the present.

Since the summer of 2016, in France but also in the United States and elsewhere, every political forecast has been systematically proven wrong. In the past few years it seems that the perverse pleasure that the public takes in contradicting pollsters — who minimize the voters’ ability to choose by presenting developments as foreordained — has turned to fierce vindictiveness. Looking only at electoral results, from the United Kingdom’s Brexit vote on June 23, 2016, on whether to remain in the European Union, to Donald Trump’s election to the U.S. presidency on November 8 of that same year, the qualità dei tempi has definitely turned to storms. The consequences for the French electoral cycle, starting in January 2017, were similarly astounding. Following a series of extraordinary circumstances that eliminated all the expected candidates one after another — those picked either as favorites or as dead certainties — the election gave the presidency to Emmanuel Macron, a man who happened in his philosophical youth to have written an essay on Machiavelli. When a journalist asked me about this electoral smash-and-grab, so characteristic of the boldness commended by the author of The Prince, I glibly described Macron as a “Machiavelli in reverse,” meaning that the French president had abandoned philosophy for politics, whereas Machiavelli chose to make his mark in philosophy when politics abandoned him.

What import does a virtuoso of political ruses like Machiavelli have for us? If he were nothing more than the wily and unscrupulous strategist that a hostile posterity has portrayed him to be, then not much at all. In these troubled times, when the stutterers can’t be told from those who are talking of the future, the last people anyone wants to hear from are the so-called experts at predicting trends, who reduce all the indeterminacy in political life to a few elementary rules of collective action. The simplicity of those rules has everything to do with the experts’ lack of imagination.

Machiavelli is that thinker of alternatives who dissects every situation into an “either/or,” drawing a crossroads of meaning at every stage of historical development. But if he is captivating, it’s because he lets us see how the social energy of political configurations always spills out of the neat constructs in which it’s meant to stay put. His sentences invariably run away with him; he has no sooner declared that there are only two avenues than he proceeds down a third. When we try to work out whether a particular political situation is going to turn out one way or another, it’s well to remember that it is carried along by a general movement that has already occurred. Perhaps this is what awaits many European and other world nations: they are so worried about a pending catastrophe that they won’t understand when it has already happened.

People who see history as primarily tragic have always felt that the scenes of our disarray might well have been penned by a ghostly Shakespeare. But as “the grotesque wheels of power” (in Michel Foucault’s phrase) grind into motion, it seems that the coarsening of public discourse we are now experiencing got its start on a less exalted stage — none other than that misleadingly named feature of Trumpian America known as “reality TV.” It is there that a general disregard for the “actual truth of the matter” (to speak in Machiavellian terms) was patiently nurtured. Not for the first time have upcoming politics had their start in fiction.

That’s why, in 2017, there was such a surge of interest in the United States in George Orwell’s 1984. Literature doesn’t predict the future any more than it protects us from its threats. It warns, yes, in the sense that it sounds the alert about a catastrophe that generally doesn’t happen, or not in the way it was imagined. Ever since 1984 came and went without bearing out Orwell’s dystopian predictions, we no longer read his novel as a foreshadowing or preview of a totalitarian regime. At this stage, we know that totalitarianism is a category not so much meant to describe a political reality as to make that reality fit into a preestablished form — for instance, at the end of World War II, when the liberal democracies were intent on demonstrating that Communism would pursue Nazism by other means.

In a sense, totalitarianism is a political fiction. It had its first trial in George Orwell’s 1949 fable and was then given a theoretical analysis by Hannah Arendt in 1951. We now know that what came after, what obtains today, took its place without receiving a name. Orwell imagined the tyranny of a “Ministry of Truth,” but that’s not what happened, and we don’t yet know if it’s for better or worse. “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears,” Orwell’s hero, Winston Smith, says in 1984. And: “Not merely the validity of experience, but the very existence of external reality was tacitly denied.” What the novel describes is the capacity of propaganda to hollow out a receptive space in people by undermining reality and sense experiences. “The evidence of one’s eyes and ears” referred to by Orwell could be common sense; it could also be that sixth sense Machiavelli spoke of, the accessory knowledge that the people have of what is dominating them.

Admittedly it was not the Party, as imagined by anti-totalitarian writers, that spoke when Sean Spicer, the White House press secretary, declared, “Our intention is never to lie to you,” before adding “sometimes we can disagree with the facts.” It’s not a Party, but it’s something else that we don’t know what to call, a fiction that is taking on body under our eyes. And what we need to understand is: What is this taking on of body, and how can our own society come to embody monstrousness? Gramsci read Machiavelli’s The Prince replacing the word “prince” with the word “party.” We could in turn read Orwell and replace “party” with “prince.” Either way, Machiavelli needs to be read not in the present, but in the future tense.

We don’t know today which Machiavellian fictions hold the resources of intelligibility that will open our future to us. Is it the philosophy of necessity expounded in The Prince and that illusionless treatise on republicanism the Discourses? Should we look in Machiavelli’s work for the art of coming to terms over our disagreements or look instead for that skill the dominated have of recognizing the science of their domination? And in that case, why not look at his theater, his histories, even his love poetry? I tried during the summer of 2016 to reconstruct the face of Machiavelli hidden by the mask of Machiavellianism; and if that face turned out to be as changeable as a storm-tossed sky, it’s because its owner hardly had the time to choose among his different talents. They all brought him back to his art of naming with precision that which was happening, his ability to take stock implacably, inextricably joining poetry and politics.

Three years later, what is the sense of spending further time with Machiavelli? The same sense, perhaps, that Walter Benjamin attributed to the very ambition of history: “To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.’ It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.” This memory is fragile and uncertain enough to awaken our pessimism. Yet if we mention anxiety, here or elsewhere, it is certainly not to paralyze our ability to act but to inject it with an element of doubt, which is the initiating impulse of knowledge. Political thought similarly has value only when it actively challenges contingencies and reversals, spurred by the recognition that the power to act is unbounded.

June 19, 2019