The Starting Point

When I was little I thought I would die before my mother, according to the principle that the tree outlives its fruit.

As time went by I came to understand the correct, or at least natural order of things, which gave me a new problem: How could I inflict on her the pain my death would bring? This realization made me careful and moderate, even as a child. My games were never particularly reckless, and I mostly stayed pretty close to her, which is something she occasionally reminds me of when I call her on Saturdays.

She lives in Athens. I have lived in Stockholm for the past forty-two years.

These are almost ritualistic phone calls. They take place preferably in the morning, soon after she gets up and is sitting with her cup of coffee on her lap. That’s how she holds her cup, resting on her stomach. She takes hesitant little sips, because she is afraid that the coffee won’t be sweet enough. The absolute minimum is three spoonfuls of sugar.

“Hi Mom, it’s me,” I say when she picks up.

If she’s in a good mood, she answers with a little poem.

If she isn’t in a good mood, she soon will be.

Good morning my son in a foreign land

who sometimes calls

and brings joy to his mother

who is older than he thinks.

You might imagine it’s the same poem every time, but it isn’t. Even at the age of ninety-two she has the ability to play with language. Then it comes: “You hardly left my side when you were a little boy, and yet you traveled so far away.”

This is not an accusation but rather a mystery she is unable to solve. I don’t have an answer either. I left my country, that’s true, but what was it I actually wanted to leave behind?

We don’t discuss the matter any further. It is what it is. My mother has always known that everything is what it is. It’s not just part of her backbone, it is her backbone, this stoical attitude to life that she has inherited, the gift of being able to let the small elements of joy defeat the great sorrows. The warm coffee cup resting on her stomach is an atomic bomb of joy, especially with four spoonfuls of sugar.

Therefore, because we both know that it is what it is, we talk about other things.

This year I turned sixty-eight, and my mother ninety-two. “I wasn’t the main cause of the First World War, but I was born in the year it began,” she sometimes says with the playful irony that has always prevented her emotions from overwhelming her.

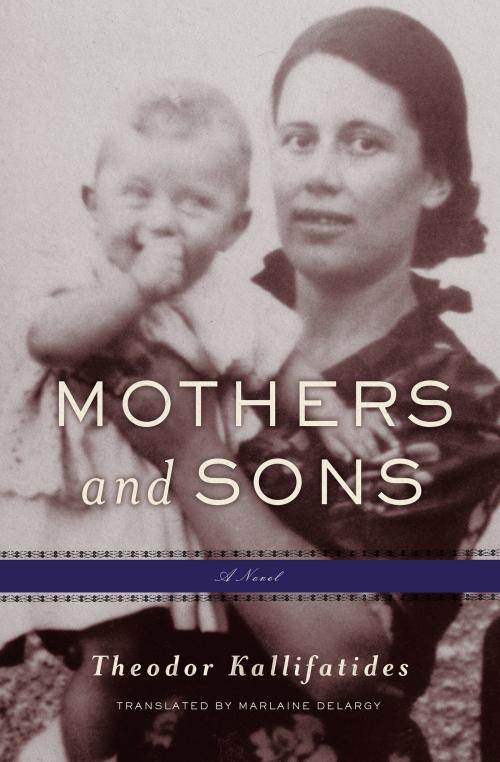

We have both grown old and it is becoming increasingly urgent for me to do what I have wanted to do for a long time: to write about her.

I didn’t want to write about her while she was still alive, but now it seems as if I have no choice. Death is approaching for both of us. We cannot know whose death is taking the longest strides.

I have to write about her, and assume that she will read what I write. It will probably turn out to be a completely different book from the one I had imagined. Right now I don’t know what kind of book it will be.

When my father died, I wrote a book about him. When his remains were dug up some years later because there was a shortage of space in the churchyard, I wrote about him again.

It was difficult, but not too difficult. My father was dead. His life was over. The book about him was already written, so to speak.

But my mother is still alive.

I am about to visit her in Athens. This time I will take my notebook with me. I have prepared a number of questions for her. I feel nervous, and I don’t really like it. I don’t want to treat my mother as material for a book. The son in me just wants to be with her like before, restfully and with no particular purpose in mind. To sit with her on the balcony, to listen to her as she complains about the government or the neighbor, to ask her to “read” the coffee grounds in our cups.

The author in me wants something else. I will be noting every gesture she makes, every word she says. How will this affect me? How will it affect her, when she realizes what I am doing?

There is no way of knowing. I remember when an eminent artist was going to paint a portrait of me. I was flattered and readily agreed, only to discover after a couple of sittings that I had stopped being myself and was behaving like someone else. The artist’s eye had colonized me and made me act like a deferential subject. If I could guess what that eye demanded of me, then I would make sure I did exactly that. Posing means looking at oneself through the other person’s eyes. That is what successful models do: They intuitively know what the photographer wants to see, and they deliver it.

I don’t want to force my mother to pose for me. How can I avoid it?

Is it even possible?

There is another problem.

How am I going to keep the writing demon, who is determined to take over, in check? The demon who wants to embroider, joke, beautify or uglify, exaggerate, turn a hen into a pheasant and a pheasant into a hen?

Few, if any other professionals, have such difficulty in sticking to reality. Talented writers are often terrible journalists. Which doesn’t mean that talented journalists are terrible writers.

Why am I worrying so much?

Then I suddenly realize what the real issue is: I will be able to continue writing only as long as my mother is alive. Once she is gone there will not be one single line more. I think.

So the question remains: How far had I moved away from her side, even though I traveled so far?

I once had a dear friend, now dead, who told me that Dostoyevsky had made her into a human being and Chekhov had made her into a woman.

I feel the urge to make a travesty of her words.

My father made me into a human being, but it is my mother who made me an author.

In my father’s world there was work, duty, perseverance, saving your tears until all the smiles had run out.

In my mother’s world, things were different. There was closeness and the nervous anxiety that goes with it; there was unpredictability, vulnerability, and the need for everything to be okay again at the end of the day. Tears and smiles were not polar opposites but a prerequisite of each other. A rapid statistical calculation tells me that my mother cried the most when she laughed the most. And above all, memory existed in her world.

Moving on was my father’s lodestar. My mother prefers to go backward.

It is from her that I have acquired my desire to tell stories. The desire that is in a way a wish for everything to be okay again, to reach the right place, to find a meaning and a context.

All of this can be expressed more succinctly. For my father, life was tomorrow.

For my mother, life is yesterday.

Their marriage was an unlikely union.

How likely was it that a boy born in 1890 in Trebizond by the Black Sea in a poor district outside the walls would marry a girl born in 1914, twenty-four years later, in an insignificant village in the southern Peloponnese? If you look at the map, you will understand. Extremely unlikely. And yet they married and lived together for almost fifty-four years.

All this is so long ago that I need to start from the beginning. As is appropriate, I will start with the dead. With my father.

When he was alive he rarely talked about his life. He was a taciturn man and the past, as I have already said, was a closed chapter as far as he was concerned. And yet he remembered everything with remarkable clarity.

This became evident when at the age of eighty-two he wrote a lengthy piece about his life, not for publication but for me. The first sentence says: “My beloved Theodor wants me to write about the origin of our family, the Kallifatides family.”

In other words, he wouldn’t have done it if I hadn’t asked him.

It is through this text that I know what I know about him and how he met my mother.

Recently, in fact on one of the very first spring days when the heart—or my heart, at least—is filled with inexplicable and inaccessible melancholy, I sat down with his text.

It was written purely for my sake. So I have to ask myself: Would it be right for me to keep it hidden from others? No, it would not. It is a testimony from different times.

It is not a story, a novel, or an essay. It is simply a life, that of my grandchildren’s great-grandfather.

So while I am at the airport in Copenhagen waiting for the plane to Athens, I take out a pen and paper and begin to translate the text for their sake. They are too young to ask me to do this, and by the time they are grown-up enough to ask, I will probably not be available.