The moment I was born, he thinks, they placed me on the back of a tiger, this is the fate of princes, to grow up on the back of a tiger; a show of strength sufficient to dazzle everyone, the sense of dominating a creature as magnificent as a tiger, feeling the tense spasms of the predator’s steely back muscles between your legs, the satisfaction of mastering a cruel-eyed killing machine that everyone fears, privilege, superiority, being seen as a god, but also fear. Yes, fear. From time to time, a cold shudder like a wet snake slithering down my back makes me tremble from head to toe.

Most princes are born doomed to be killed, he thinks. In our family, have babies not been strangled with eighteen of their older brothers while their mother’s milk was still wet on their lips, have silk cords not been wrapped around the necks of hundreds of princes who could not become sultan? He wonders if most of those who were allowed to live went mad after being imprisoned for years in boxwood cells, fearing that each approaching footstep was that of the executioner. He tries, meanwhile, not to think of the brothers he has kept in prison for years.

In this world, you are either the head of state or a raven’s carcass. When you’re on the tiger’s back, you control a great power that obeys your every command, you’re mighty, and happy; however, the moment you dismount, the tiger will shred you with its claws like a poor gazelle, it will never hesitate. The only way to live with the tiger is to be its master; you are either its master or its prey.

I didn’t choose this, he thinks, no one gets to choose the family they’re born into, we all come into the world with our own destinies; in a sense, our fate is to be born on the back of a tiger. You can’t change your destiny.

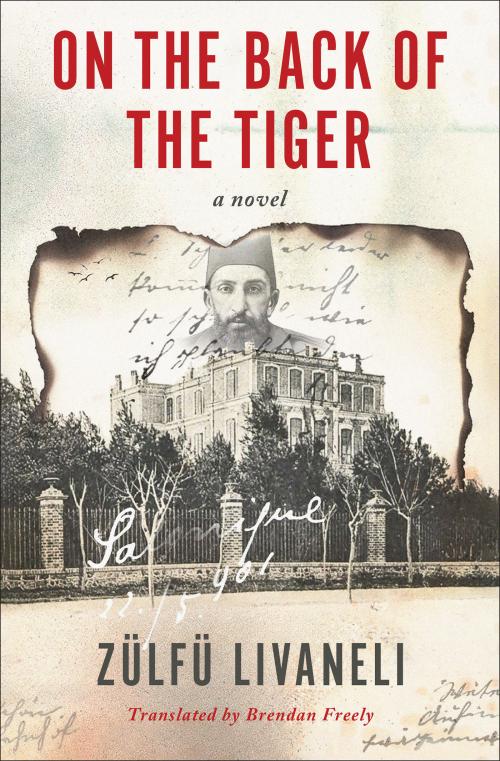

Part One

April 28, 1909

The first night of exile in Thessaloniki— Ice cream at midnight—Imperial paranoia— La Traviata

On that dark night, Abdülhamid II, the thirty-fourth Ottoman sultan and caliph of the Islamic ummah, pushed himself up off the floor with his right hand, and as his left hand searched for something to hold on to, he touched something soft. He attempted to stand by leaning on it. His arm, his leg, and his hip were hurting. When he was on his feet, he took the lighter he always kept in his caftan pocket and lit it; the flame partly illuminated the dark room, but what he saw in that faint light made his heart tremble even more. First he looked at the object he’d leaned against. A large, dark armchair, he couldn’t make out the color, it seemed to be upholstered in velvet, another matching armchair was pushed up against it. Not back to back, but with the seats facing each other. At that moment the sultan remembered everything, it was as if a sudden bolt of lightning had struck his aging body. He was not in the palace in Istanbul, the city in which he’d woken every morning for thirty-three years, he was far away. He was imprisoned in a room in a mansion in Thessaloniki. He held up the lighter and looked around; as his arm moved, the faint light flickered across the decorations on the high ceiling, the shuttered windows, the brown floorboards, and the two armchairs.

The sultan felt an indescribable sense of strangeness. He found himself in this strange room, hungry, deprived, and alone. His children, wives, and servants must have been lying on the floor in various rooms of that empty mansion. After they’d been brought to the mansion and the soldiers had locked the wooden double door, they’d found themselves in a large, empty hall that contained nothing but a dining table. They sat on the floor and hung their heads as if they were embarrassed to even look at one another. Sometime later his eldest daughter had seen the two armchairs that had been forgotten in a corner. Cumbersome armchairs upholstered in dark green velvet. With his daughters’ help, the servants carried the armchairs to the room on the left, pushed them together, and said, “My sultan, rest here for tonight and we’ll work everything out tomorrow. Your own soldiers would never leave you in these conditions, they must not have had time to get everything ready.” Just then he heard the mansion’s gigantic door open and saw a commander enter, accompanied by soldiers carrying lamps. It was a stern, soldierly entrance, and the aging sultan, who all his life had feared assassination, felt his nerves on edge. The sound of their boots echoed through the empty mansion, the lamps lengthened the shadows, the severe looks the soldiers gave him and his family and the commander’s relatively civilized expression announced that their last hour had arrived. Perhaps they would be lined up right there and shot, perhaps, like everything else, the custom of not shedding dynastic blood was a thing of the past. He noticed that his children stepped in front of him as if to protect him. His wives, his three daughters, and his eldest son were shielding him. The commander, who must have understood what they were thinking, said, “Sir, we’ve brought you food and water.” The soldiers behind him carried in a large round tray and placed it on the table that stood in the middle of the hall like a statue of loneliness. The commander said, “Please excuse us, your arrival was so sudden we didn’t have time to get the mansion ready. Robillon Pasha was living here, he was ordered to move so he took his furniture and left. Hopefully tomorrow we can procure some beds and things from the hotels.” The commander seemed sympathetic to the royal family’s plight, but the others continued to regard them with hostility.

“Thank you, officer,” said the sultan. “Bless you. What’s your name?”

“Ali Fethi, sir. I came from Istanbul. I am responsible for you. They said they had this food prepared at Pastacıyan, the best restaurant in Thessaloniki,” said the commander. If only he hadn’t, because as soon as the sultan heard about food having been prepared, his legendary “imperial paranoia” reared its head and his fears returned. It occurred to him that they were going to be poisoned. He could not eat this food, but he could not refuse it either. He had to find a solution at once. “Commander, my stomach is upset,” he said. “I can’t eat this. If it’s possible, I would like some yogurt and some mineral water.” Surprise registered on the commander’s swarthy face, but still he agreed to the sultan’s request and ordered one of his men to bring yogurt and mineral water.

The soldier rushed out the front door and returned almost immediately. The sultan looked suspiciously at the bowl of yogurt and the unopened bottle of mineral water, but supposed they wouldn’t have had time to mix in the poison. Besides, the commander was winning his confidence. He thanked him. As the commander was leaving, he patted the sultan’s youngest son on the head and murmured something. Later Zülfet, the overseer of the servants, who’d been closest, reported that he’d said, “Poor little boy,” and this led him to begin liking and trusting the commander.

As soon as the front door was locked, the hungry children rushed over to the tray and began lifting all the lids. Unfortunately they were disappointed by what they saw. Most of the plates were empty; there was some yogurt and a few slices of bread but—strangely—there was lots of ice cream. The sultan’s family had been taken from the palace and put on a train the day before, they’d been hungry for hours, whose crazy idea had it been to offer them ice cream at that hour? It was clear that the honest-looking commander had no idea about this. He’d responded to the sultan’s thanks by bowing respectfully, but not everyone in the army was his friend. The revolutionaries, the guerillas, and the pro-French officers hated the sultan and blamed him for all that was wrong. Perhaps he had more enemies than friends in his own army. Otherwise, when they entered the city to put down an insurrection, would they have taken him from his palace and packed him off to Thessaloniki? The children ate a bit of yogurt and bread and then, as they were about to turn their attention to the ice cream, the sultan shouted, “Stop! Do not eat that ice cream!” It was clear that the poison was in that ice cream. Why else would they send something so meaningless? The family, gathered around the table, stopped in surprise and pulled back their hands, but he saw that his eldest son already had some ice cream on his mouth. Oh no, he said to himself, my son is gone, my prince is gone. There was no silverware on the tray. There was nothing to eat with. So the prince had stuck his finger into the ice cream. They thought this was why their father had shouted, “Stop!” They were civilized children who had grown up in the palace, they knew all the rules of etiquette and politeness, they’d had private tutors teach them piano, singing, French, and Italian. Surely they would know better than to eat ice cream with their hands.

The sultan realized this, and decided not to say anything. In any event, his son had already eaten the ice cream, it was too late. There was no point in frightening the boy, and perhaps he was being paranoid for nothing. He quietly withdrew to the room that had been prepared for him, holding a bowl of yogurt and an unopened bottle of mineral water. He stopped in the doorway and addressed his family and the servants. “May God grant you peace. Our Lord knows what’s best for us. He protects us and watches over us. We will see what tomorrow brings.” More than thirty people politely wished him good night, then after he had closed the door, the family began eating the ice cream with their fingers. When they’d had their fill, the servants gathered to finish the rest.

The sultan took out the pocketknife he always carried, ate some yogurt with it, used it to open the bottle of mineral water, then after quenching his thirst he curled up on the armchairs. Indeed at the palace—especially during the day after eating—he would lie down on lounge chairs in various rooms, he found beds uncomfortable and occasionally slept under the bed. It had astounded him to see the children eat ice cream with their fingers despite their rigorous upbringing. Even the snow-white Angora cat that seldom left his lap at the palace wouldn’t eat anything that was not offered on a fork. She was such a well-behaved, noble creature. Still, he’d seen enough of life to know that hunger could make a person do anything. During the endless wars, people even ate their sandals. But he had taken good care of his army, making sure never to leave them without rations. “May God not punish anyone with hunger,” he murmured.