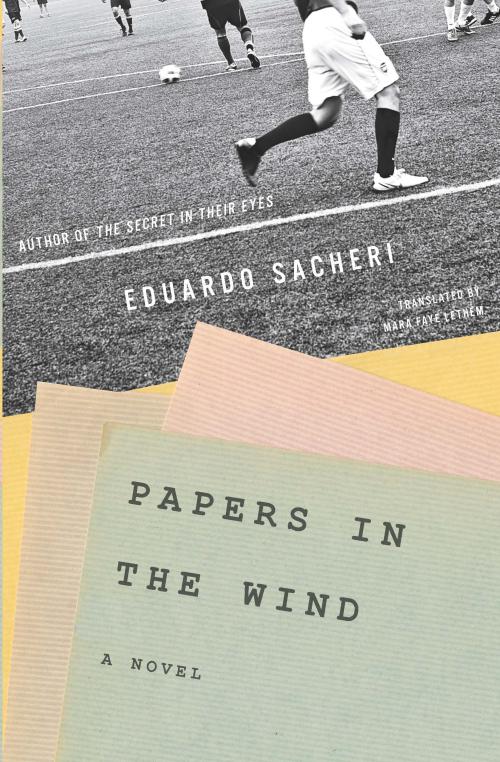

When Mono finished high school he had his future crystal clear. The next year they would offer him a professional contract to play for Vélez. In three or four seasons he would become the best number four in Argentina. At twenty-three—twenty-four, at the most—he would be traded for millions to an Italian team. Then he’d play about twelve seasons in Europe. Finally, he’d return to his country to finish his career with Independiente and retire on a high note. But the verbs Mono was conjugating in a self-assured conditional tense didn’t stop there.

Once he retired, and in order to continue his association with the world of soccer, he would become a coach. He’d start running a minor-league club and after a few seasons of experience he’d make the t some point, before or after, as a player or as a coach—or better yet, before and after, as a player and as a coach—he would take Argentina to another world title, after defeating England or Germany in the semifinals and Brazil in the final game.

He had dreamed of it so many times, and he had talked about it so many times—because Mono was convinced that you shouldn’t keep your great joys quiet, not the ones in the past tense and not the impending ones—that his friends could repeat his future biography to the smallest detail. Fernando and Mauricio both saw it as a waste of their time, but Ruso would get really excited about it, taking on the roles of agent, masseur, assistant coach, or image consultant, de-pending on his mood.

Sadly for both of them, when Mono turned twenty he was called in to see the secretary of Vélez Sarsfield, and they notified him of the only verb in conditional tense he wasn’t prepared for: he would be released, because the club had decided they had no need for his services.