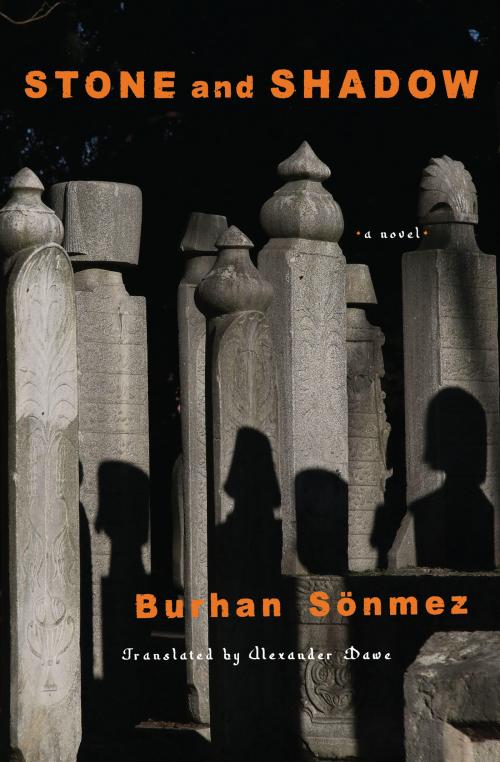

Merkez Efendi Cemetery

Istanbul, 1984

Avdo considered the gravestone he would make for the dead Man with Seven Names whom they had buried today. He drew on his cigarette, took a sip of tea, and thrusting forward the fingers of his hand that held the cigarette as if he were talking to someone, he thought to himself, the gravestone would have to be black and with a hole in the center. You should be able to see the emptiness on the other side. The void should grow and deepen the more you looked. The dead man had been a soldier. When they found him stretched out on the bank of the Euphrates during the Dersim military operation, he was unconscious, his memory gone. They told him his name was Haydar and that he had been wounded by a band of Kurdish Zazas and had to rejoin his unit. Soon he was armed and made good use of his whip as the enemy was rounded up and driven barefoot into exile. The journey was long and Haydar sometimes felt light-headed, as if he might fall, but he was convinced of who he was and what he was doing. When they stopped at a camp, an old blind man among the prisoners, half of whom had already perished, recognized his voice and said they came from the same village. What happened to him, the blind man asked, and he told Haydar his past. His real name was Ali. During the roundup, he must have been shot on the riverbank while fleeing from the soldiers. Realizing he had lost his memory when they found him and telling him that he was a soldier, they had given him a new past, and a new future. After listening to the man, Haydar fled to the Mesopotamian Plain in the south, where he came to believe he had no one identity. There the plain spoke to him: You are neither Haydar nor Ali, as you have no memory of childhood, and with no memory of those years, you will never know who you really are. He walked the earth, following the stars. He took refuge in God and read every book he found in search of an answer. From Jerusalem to Cairo, Crete to Athens, Rome to Istanbul, he wandered for forty years, finding a new name and a new religion in every city where he made his home. Today he had been brought to the Merkez Efendi Cemetery in a coffin draped in faded muslin, his seven names written on a piece of paper: Ali, Haydar, İsa, Musa, Muhammed, Yunus, Adem. He had spent his last week in bed. In his crowded room, he kept a letter and a bag for his neighbor who came to see him; when he died, they were to be delivered to the gravestone master Avdo.

After everyone had left and the cemetery was silent and a fog was falling over Istanbul, Avdo opened the letter:

Avdo, I am entrusting you with the work of my gravestone. I have gone by many names; I have adopted many religions. In the end I have no one faith. And with so many names, I have none. I met you when you were a child and when you sang so beautifully. Your name has been on my mind, Avdo, I don’t even remember what mine was then. Maybe you do. Last year I happened to learn that you lived at this cemetery. I heard what happened. I couldn’t come. Surely you were already busy enough with all the dead around you. They told me that your gravestones always fit the spirit of the dead. Make one for me. Let my gravestone say to the universe: The only evil of God is that he does not exist. Make a gravestone for this. I am including some money with this letter to cover expenses and for those songs you sang when you were little. I am also leaving a few other things in my bag that may be of use to you.

With a sigh, Avdo put the letter in its envelope after reading it twice. Looking at the fog falling over the graves, he wondered what voices would come tonight. On these foggy nights he sometimes heard the voices of his childhood, sometimes the wailing of the dead. Reading the letter, he had felt as if his barefooted childhood was watching him through the fog. There stood that little boy several feet away like a patient cypress. Softly stirring and with every step the crackling of dry branches. With every rustle, his childhood came to life in sound. Laughing, singing, and shouting unraveled in threads that paid no heed to the wailing dead. Once again Avdo heard these voices and he was content. Leaning back, he lent his ear to the night. He remembered his past, he knew who he was, for he knew his name. He was not like the Man with Seven Names. In the guarded trunks of his mind, he kept all he had endured over the years. He remembered even the oldest melodies; the words were still fresh in his mind. He thought of a song he used to sing in the markets and squares, a song that fed him. He murmured the melody then softly he began to sing so as not to wake the dog that was sleeping at his feet.

Oh beloved, don’t squander my day, One day lasts as long as a lifetime.

Oh beloved, don’t throw my gleaming life in the cave, A lifetime lasts as long as one day.

When he sang at the base of those cold walls, the women would come out from their houses and caress the head of the child who sang with such passion. They gave him bread, warm milk, sometimes a bed. He was glad, and like every other orphan, he took refuge in their compassion, in their hands and breath. He experienced the most beautiful sleep in their homes. Dreaming the woman was his mother, he closed his eyes with the hope of waking up in the morning to find out that his dream had come true. Those nights were as long as a lifetime. In the morning he opened his eyes and looked lovingly on the mother of the household and told her his dream: An old man in a graveyard was chiseling a stone, keeping him safe from the cold, letting him play with his dog. The old man missed his mother, too, a mother he had never seen.

Who was dreaming? Was old Avdo dreaming of his childhood or was young Avdo dreaming of his older self?

On the radio they announced this was going to be the longest night of the year. The fog would lift at midnight and toward dawn it was going to snow. The city would fall asleep in the storm and wake up in white. Surviving the wet north wind that swept over the sea was no easy task, and the cold seeped into your bones. Avdo had a home with a strong roof and sturdy walls and he had his fire. On nights like these he left his outside light on. This was a lighthouse for the homeless. If only his dog Toteve could give some kind of signal to the street dogs, howling them over. But the old beast now lay under the table, stretched out in a world of peace. For the last hour he had not budged. He was getting on in years and took every opportunity to rest, climbing into the little den he had dug behind the house where he passed the daytime hours. Lately he had lost his appetite, he often left his favorite mash unfinished.

Avdo was getting older, too. His beard had gone gray and he was losing his teeth; he knew it from the chill that often took hold of his back. His arms were still strong and he worked throughout the day on his feet, hauling marble and stone. His large body gave him no complaints, save the icy spot in the middle of his back. He felt it in the fall winds and in December he avoided the cold. The fire from the little grill beside his table warmed his tea but it no longer kept him warm. He had taken to wrapping a blanket around his back whenever he sat down. The coldest time of the year, the zemheri, had a hold on him.

He stirred three spoonfuls of sugar into his tea and lent his ear to the sounds in the pale darkness. Somewhere over the shrine in the western side of the cemetery he heard the cry of an owl. He stared out into empty space as he struggled to pinpoint exactly where she was. Night was not silence but rather distilled sound. The many different sounds of day turned into clamor, but the sounds of night emerged distinctly. The songs of childhood, the wailing of souls, the crying of an owl. None of it was clear in the chaos of day. The same went for longing and pain. Alone you could feel pure pain at night. The water that now ran from the fountain by the redbud tree in the darkness conjured up those old laments, the sadness of a lover lost years ago twisted around the heart. In the day, it was easy to carry the burden; at night you truly believed that you were alone.

The souls also believed they were alone in the world, their wailing now slowly drifting through the fog. Every morning they rose thinking the sun was rising for them, they found consolation in a thousand and one dreams and in the footsteps of visitors who went among the graves. They lingered in the tumult of the world, losing track of time, until evening fell again. They trembled in the twilight, and as the dwindling light mingled with the gathering dusk, they came to understand their lack of fate. There was sadness and fear. Who could help them? An owl, an old dog, and Avdo. The only ones listening to them as they prayed to the sky.

Avdo looked across at the souls wailing in the cemetery. Our God, they cried, if You are not, then how have we found hope? Our God! You have left us in this world with a fleck of hope but staring into the face of despair.

Avdo smiled. The poor dead, he said under his breath.

You can’t choose your place of birth, but you can choose where you will die. Yet those in the cemetery only understood this once they had died. Chasing desires all their lives, not one of them had ever stopped to think where they might like to die. Now suddenly finding themselves down in the earth, they let out terrible cries. Avdo had thought about it before. In a dark abyss that was as long as a night. It was years ago that he had settled here with the decision that this was where his life would end. He dug his grave beside the grave under the redbud tree, placed a nameless gravestone above it. His smooth, long-suffering stone. On that day he would lie down beside the woman who was waiting for him. On that peaceful night a silver star would shoot across the sky. On that long, dark night. Our God!