It happened in The District, at Bule Marsh. Eddie’s death. She was lying at the bottom of the marsh. Her hair was standing out around her head in thick, long strands like octopus tentacles. Her eyes and mouth were wide open. He saw her from where he was standing on Lore Cliff, staring straight down into the water. He saw the scream coming out of her open mouth, the scream which could not be heard. He looked into her eyes, they were empty. Fish were swimming in and out of them and into her body’s other cavities. But later, when some time had passed.

He never stopped imagining it.

That she had been sucked down into the marsh like into the Bermuda Triangle.

Now she was lying there and was unreachable, a distance of about thirty feet, visible only to him, in the dark and murky water.

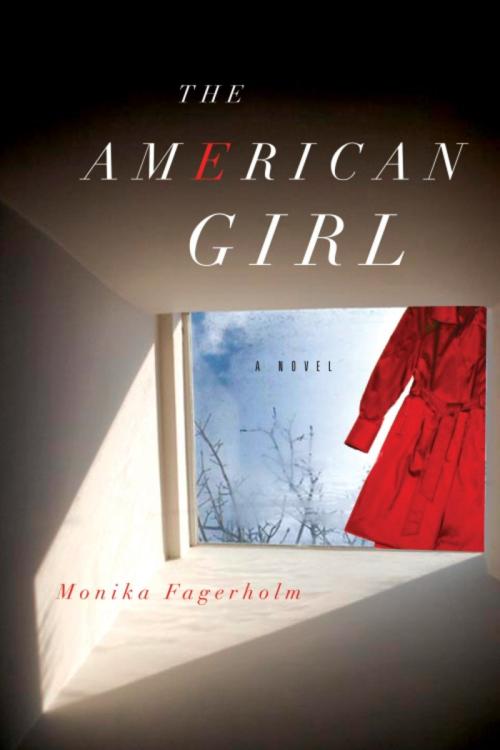

She, Edwina de Wire, Eddie. The American girl. As she was called in The District.

And he was Bengt. Thirteen years old in August of 1969 when everything happened. Eddie, she was nineteen. Edwina de Wire. It was strange. Later when he saw her name in the papers it was as if it was not her at all.

“I’m a strange bird, Bengt. Are you too?”

”Nobody knew my rose of the world but me.”

She had talked that way, using peculiar words. She had been a stranger there, in The District.

The American girl. And he, he had loved her.

There was a morning after night, a night when he had not been able to sleep. At daybreak he ran through the forest over the field over the meadow past the cousin’s house, the two decayed ramshackle barns and the red cottage where his sisters, Rita and Solveig lived. He jumped over three deep ditches and got to the outbuilding by the border of Lindström’s land.

He walked into the outbuilding. The first thing he saw were the feet. They were hanging in the air. Bare feet, the soles gray and dirty. And lifeless. They were Björn’s feet, Björn’s body. Cousin Björn’s. And he was also only nineteen years old that same year, when he died by his own hand.

They had been a threesome: Eddie, Bencku, Björn. Now it was only him, Bencku. He was left alone.

And so, he stood and screamed out into the wild dazzling nature of late summer, so quiet, so green. He screamed at the sun which had just disappeared behind a blue cover of clouds. At a dull, calm summer rain cautiously starting. Drip-drip-drip, in an otherwise total and ghostly calm. But Bencku screamed. Screamed and screamed, even though he suddenly did not have a voice.

He became mute for long periods of time. Thoroughly mute: he had not spoken that much before, but now he was not going to say anything at all. According to the diagnosis, a clinical muteness brought on by a state of shock. As a result of everything that had happened during the night.

Another child was also moving around in The District then. She was there at all possible and impossible times of day, in every place, everywhere. It was Doris, the marsh kid. Doris Flinkenberg who did not have a real home then despite the fact that she was maybe only eight or nine years old.

It was Doris who said she had heard the scream at the outbuilding by the border of Lindström’s land.

“It sounded like a stuck lamb or the way only someone like Bencku sounds like,” she said to the cousin’s mama in the cousin’s kitchen in the cousin’s house where she gradually, after Björn’s death, would become a daughter herself, in her own right.

“It’s called a pig,” the cousin’s mama corrected her. “To squeal like a stuck pig.”

“But I mean lamb,” Doris would protest. “Because that’s what Bencku sounds like when he screams. Like one of those lambs you feel sorry for. A sacrificial lamb.”

Doris Flinkenberg with her very own way of expressing herself. You did not always know if she was serious or if she was playing a game. And if it was a game, in that case, what kind?

“One man’s death is another man’s breath,” Doris Flinkenberg sighed in the cousin’s kitchen, so delighted over finally having her own home, a real one. Only someone like Doris Flinkenberg could say “One man’s death is another man’s breath” in such a way that it did not sound cynical, but actually, almost normal.

“Now, now, now.” The cousin’s mama said to Doris nevertheless, “What are you actually saying?” But there was still something soft in her voice, in a calm and settled way. Because it was Doris who had come to the cousin’s house and given the cousin’s mama her life and all her hopes back after the death of Björn, her darling boy.

But who could have imagined then that only a few years later Doris would be dead as well.

It happened in The District, at Bule Marsh, death’s spell at a young age. It was a Saturday in the month of November. Dusk slowly transformed into darkness and Doris Flinkenberg, sixteen years old, wandered through the woods on the familiar path down to Bule Marsh. With quick and determined steps. The growing darkness did not bother her, her eyes had time to get used to it and the path was familiar to her, almost too familiar.

And it was Doris Night, or was it Doris Day, or was it the Marsh Queen or one of the many other identities in the many games she had already had time to play in her life? You did not know. But maybe it was not important anymore.

Because Doris Flinkenberg, she had the pistol in her pocket. It was a real Colt, certainly antique, but in working condition nonetheless. The only thing of value that Rita and Solveig had ever inherited from anyone: a distant ancestor who, according to rumors, had bought it in 1902 at the big department store in the city by the sea.

Afterwards, when Doris was dead, Rita would swear she did not know how the pistol, which was stored, hidden away in a specific spot in hers and Solveig’s cottage, had gotten into the hands of Doris Flinkenberg.

It would not be a complete lie, but also not entirely true.

Doris came to Bule Marsh and she walked up Lore Cliff. She stood there and counted to ten. She counted to eleven, twelve and fourteen too, and to sixteen, before she had gathered enough courage to raise the pistol’s barrel to her temple and pull the trigger.

She had already stopped thinking, but her emotions, they swelled in her head and her entire body, everywhere.

Doris Flinkenberg wearing the Loneliness&Fear shirt. Old and worn now. A real cleaning rag, that was what it had become by this time.

But anyway, in the space between two numbers the resolution had taken hold of Doris Flinkenberg anew. And she just raised the barrel of the pistol to her temple, and, click, she pulled the trigger. But first she shut her eyes and screamed. Screamed in order to drown herself out, to drown out her fear, and the shot itself, which she would not hear anymore, so that was even more absurd.

Shots, I think I hear shots.

It echoed in the woods, everywhere.

It was Rita who heard the shot first. She was in the red cottage about a third of a mile from Bule Marsh with her sister Solveig. And it was strange, as soon as she heard the shot she knew exactly what had happened. She tore her jacket from the wall and ran out, through the woods to the marsh with Solveig after her. But it was too late.

Doris was already dead as a rock when Rita made it to Lore Cliff. She was lying on her stomach, with her head and hair hanging down over the dark water. In blood. And Rita lost it. She tore and pulled at the dead and still warm body. She tried to lift Doris up, and how absurd was that, to carry her.

Carry Doris over troubled water.

Solveig had to do everything in her power to try and calm Rita down. And suddenly the woods were filled with people. Doctors, police officers, ambulances.

But. Doris Night and Sandra Day.

In one of their games.

They had been two actually. Sandra and Doris, two.

Doris Day&Sandra Night. That was the other girl, she had also had many names which they made up during their games. Games which had been played with the best friend, the only friend, the only only only, Doris Flinkenberg, at the bottom of the swimming pool without water, so far. It was Sandra, she was bedridden for weeks after Doris’s death, in a four-poster bed in the house in the darker part of the woods that was her home. She lay with her face turned toward the wall, knees bent and pulled up toward her stomach. She had a fever.

A stained, worn nylon t-shirt under the big pillow. “Loneliness&Fear”: the other copy of the only two in the history of the world. She squeezed the shirt so hard her knuckles turned white.

If she closed her eyes she saw blood everywhere. She was in the Blood Woods, wandering there in the darkness, confused, like a blind person.

Sandra and Doris: it had been the two of them, they had been best friends.

And, only Sandra Wärn out of everyone knew this: Sister Night&Sister Day. It was a game they had played. And in just this game she had been the girl who had drowned in Bule Marsh many years ago. She who was called Eddie de Wire. Her, the American girl.

The game had another name as well. It had been called The Mystery with the American Girl.

And it had its own song. The Eddie song.

Look mom, they’ve destroyed my song.

And all the words and peculiar sayings had also belonged to the game.

“I’m a strange bird, are you too?”

“The heart is a heartless hunter.”

“Nobody knew my rose of the world but me.”

But, shadow meets shadow. There, in the darkness, those weeks when Sandra did not leave her room, it happened sometimes that she crawled out of bed and stood by the window and looked out. Looked out over the muddy landscape out there, over the familiar, low-lying marsh, over the clump of reeds…but more than anything toward the grove off to the side. That was the direction in which her gaze was drawn. That is where he was usually standing.

And he was standing there now, looking at her. Her behind the curtains in the room with the lights out. Him out there. They stood there across from each other, and stared at each other.

One of them was the boy, and he was Bengt. Quite a bit older now. The other was the girl, Sandra Wärn. Who was the same age as Doris had been when she died, sixteen years old.

2008, The Winter Garden. Johanna is walking in The Winter Garden. And everything is still there, these many years later.

In Rita’s Winter Garden, a park, a world all by itself. A defined space for entertaining, recreation, enchantment.

A world in and of itself, for games, also adult games.

But at the same time it is an intricate combination of public and private, conventional and normal, but also the secret, forbidden.

Because there are things in The Winter Garden you do not talk about, things you only imagine. Underground and above. Secret rooms, a labyrinth.

You can walk down there and experience almost anything.

All of the old things, in their own way. The District and its history are also in The Winter Garden. Like pictures on the walls, names and words, music.

Carry Doris over troubled water.

Death’s spell at a young age.

Nobody knew my rose of the world but me.

I walked out one evening, out into a grove so green.

Shots, I think I hear shots.

Look mom, they’ve destroyed my song.

In the middle of The Winter Garden there is Kapu Kai, the forbidden seas.

Loneliness&Fear

Doris Night. And Sandra Day.