CHAPTER 1

Once upon a time, I was a Bolshevik.

A fictional Bolshevik, but a flesh-and-blood Bolshevik just the same, with a leather jacket, a red bandanna around my neck, and a glint in my eye. In those days, the walls of my apartment were covered with posters from the October Revolution. You could see entwined rifles and hammers, circles pen- etrated by triangles, raised fists, and slogans shaped like allegories: “Beat the Whites with a Red Wedge!” Locomotives roared skyward, and workers in red tunics pointed at the class enemy or the deserter. Astride a globe with a broom in hand, Lenin swept the last exploiters from the surface of the Earth. My dreams echoed with onomatopoeia written in gigantic repeated letters, as in Eisenstein’s films: HO, HO, HO.

Streaming in from everywhere, the masses became a physical force on encountering the Marxist theory of surplus value. From the moment I awoke, the picture on the wall of a man with a bloody bandage around his forehead charged me with his implacable energy. The genie of electricity lit up the world. The Soviets did the rest.

The masses rushed into the great theater of history. In the wings, the actors waited for the curtain to go up to run onstage and deliver the words that the crowd had been anticipating for so long. Slogans burst from fiery mouths. It was no longer the orators speaking to the people, but History itself dictating their words, as if the aim of those Bolsheviks with nerves of steel was to melt and merge with it.

During revolutions, women’s charms fade in the eyes of men, they say. History takes their place. It haunts men’s dreams. In one such dream, Lenin is forever haranguing the Petrograd crowd from his balcony, cap in hand. Trotsky’s train is thundering after Kolchak’s and Denikin’s armies, spanning vast spaces and desolate distances.

A youngster of seventeen shoots an ambassador at point-blank range. “The revolution chooses its lovers young,” Trotsky told the German generals, who were astonished at having to negotiate peace with adolescents. The reason is simple: they kill more easily.

Back then, I could recite whole passages of Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry and had embraced Dziga Vertov’s manifesto “I Am an Eye!” (“Flee the sweet embraces of the romance, the poison of the psychological novel, the clutches of the theater of adultery”). This was probably the source of my later rejection of psychological narrative and the so-called bourgeois novel.

But my breviary, my bible, was The Iron Heel, by Jack London, though I have forgotten its plot and major episodes. I only remember the scene in which the hero Ernest Everhard proved capitalism’s inevitable breakdown. “You say I’m dreaming?” said the young labor leader. “Very well, I’ll demonstrate the mathematics of my dream!” Ernest Everhard was my politico-literary superego: he had an answer for everything.

Those were the richest, craziest, most passionate years of my life. I was in love with Alexandra Kollontai, history’s first female ambassador. Isadora Duncan and Sergei Esenin were the most extravagant couple in Moscow. She had abandoned the stages of Europe for an unheated palace in Moscow, where “she made proletarian children dance.” From Bolshevism, I especially retained its period of genius, history’s first proletarian revolution, and maybe also its last. My historical clock stopped in 1923, when the New Economic Policy (NEP) followed the heroic years of War Communism. What happened afterward, the trials and Stalinism, didn’t concern me. That was another period, Thermidor or Restoration. My subject was the transition.

I was a Bolshevik of the 1980s, further to the left on questions of society and culture than on the role of the vanguard party or the collectivization of farmland, for example. I was very free concerning morals and the institution of marriage, but inflexible on principles of communal life and the sharing of domestic chores. With Bolsheviks like me, the tsar could rest easy.

Once a week, all of us Paris Bolsheviks would gather in a big auditorium at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales on rue de Varenne. In a dense fug of cigarette smoke, our professor of Bolshevism would explain—with statistics at hand—how the failure of grain harvests at one particular moment led to the fatal rupture of the peasant-worker alliance, and everything that followed. We wanted to understand the specific conditions of the processes of transformation, its dead ends and historic errors, so as not to repeat them in the revolutionary period that was sure to begin for us. Sometimes the seminar would go on late into the evening in a back room of a bistro near the Arts-et-Métiers metro. When I was feeling melancholy, I would sometimes repeat the famous testament by Nikolai Bukharin—condemned to death by Stalin—that his young wife, Anna Larina, learned by heart during his years in exile: “Comrades, know that on the banner you will be carrying in the victorious march to communism there is also a drop of my blood.” Confronted with Stalin’s crimes, we wanted to rebuild Marxism on the bedrock of lived experience. And to do that, we focused on field study: the “Bolshevik years” were ending, and we were turning into sociologists.

It was in the course of moving that my Bolshevik past resurfaced. Thirty years had passed. I had just moved into a house on the banks of the Marne. The electricity hadn’t been turned on yet, and the house lay in semidarkness. Using my smartphone flashlight, I picked my way among the piled chairs, box springs, trestle desks, and boxes of books stacked to the ceiling.

For the first time ever, I had enough room to unpack my library. Up to then, it had been scattered among various storage units. Years passed between one box and the next, and moving among them gave me the impression of crossing decades, disturbing slumbering periods. Breathless from my comings and goings, I sat down on an old trunk that the movers had left in the middle of the living room. It was a greenish tin trunk with dented corners, covered with freight stickers. Taped to the lid was a half-erased label I could just decipher in the dim light: bl kin ject 79—probably a shipping label.

Intrigued, I released the hook holding the two metal tabs of the latch and lifted the lid, which opened with a creak. The trunk was full of books, lying side by side in a single patchwork layer. They had spent years in the dark, huddled together like stowaways, migrating from one basement to another without ever seeing the light of day.

I picked one up and shone my phone light on its cover. The Start of an Unknown Era, by Konstantin Paustovsky, published by Gallimard in its Soviet Literature collection. On the back cover, this sentence appeared, after a date: “1917: The story of a man is written in the story of a country.” I gently laid the book at my feet and reached for another one, whose title in red capital letters filled the entire page: People and Life, by Ilya Ehrenburg. On its back cover: “A patriot says he comes from the biggest country in the world, the country that is pursuing the most fascinating social experiment.”

The cover of an old paperback showed a drawing of a mustached man staring fiercely through the bars of his cell at prisoners exercising in a snow-covered prison yard. This was Arthur Koestler’s famous novel Darkness at Noon. Opening it to the frontispiece, I saw the first and last names of a sixteen-year-old girl, written in an adolescent’s rounded letters. At some distant time the book had belonged to the person who became my daughter’s mother. As I leafed through a volume of V. I. Lenin’s Complete Works published by Éditions sociales, a few grains of sand fell from between the pages. So I’d been reading Lenin at the beach! My Life, Leon Trotsky’s autobiography, lay next to The Noise of Time, a collection of prose pieces by Osip Mandelstam. Trotsky and Mandelstam. War and Poetry.

Sweeping my phone light across the trunk’s contents, I paused at Platonov’s The Foundation Pit from L’Age d’Homme, which had republished whole swaths of Russian literature in its Slavic Classics collection. In the same ocher binding, beneath a logo formed by the letters C and K—whose meaning I forget—was Andrei Biely’s Petersburg, Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, Yuri Olesha’s Envy, Leonid Leonov’s The Thief, Nikolai Leskov’s No Way Out, Mandelstam’s The Egyptian Stamp, Zamiatin’s A Story About the Most Important Thing, and Sergei Esenin’s Confessions of a Hooligan. Each of those titles had been familiar to me in a previous life, and I had forgotten their contents. Some of the books were dog-eared, tagged with multi-colored Post-it notes, their covers cracked, stained with damp. Glossy surfaces had worn away, letting the paper’s grain show through, like the translucent skin of an old man.

I could make out blurry pencil marks in the margins, notes from old lectures, unreadable in places, like commentaries that time hadn’t retained. Passages, underlined or crossed out, revealed tastes, states of mind, opinions that seemed to belong to some other person. A drawing by my daughter at age three was slipped between the pages of an essay on the GPU, revealing the real date in my memory of that distant era with the precision of carbon-14 dating.

Under the first layer of books lay crushed archive boxes, notebooks in various formats, cardboard slips covered in blue writing that was fading to purple here and there, even an old red-and-black typewriter ribbon. There was a jumble of newspaper clippings, tracing paper covered with city maps, spiral-bound notebooks, and cassettes with unspooled magnetic tape, their plastic cases cracked, boxes of photos, ring binder sheets, handwritten manuscripts, historians’ articles, accounts by GPU agents who had defected to the West, photocopies of police reports, a floor plan of the Lubyanka prison, a scene-by-scene breakdown of Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin . . . A postcard fell out of Isaac Babel’s Odessa Stories; it had probably served as bookmark. On the right-hand side of the card was an address: “Quinta La Rivera Prolongation av. principal de Santa Ines Caracas, Venezuela.” That must have once been my address, but I didn’t remember it.

On the other side I read these words written in red ink:

“Salutations, oh vanished one! I got your February letter yesterday, because I have vanished as well. The beauty of clandestine life! Good luck with the writing. Best wishes, Milan.”

With pins and needles in my legs, I stood up and closed the trunk. The half-erased inscription on the lid, bl kin ject 79, which I’d thought was a shipping label, suddenly came back to me: blumkin project 1979. The Blumkin Project.

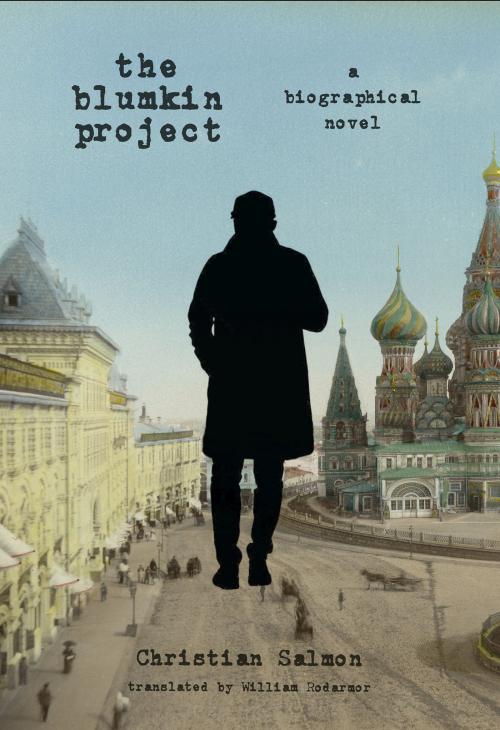

This trunk held the archives I had assembled years earlier about a legendary character in the October Revolution, Yakov Blumkin. It was he who, on the orders of his Left Socialist Revolutionary Party, had assassinated the German ambassador to Moscow in 1918. The act was a protest against the “infamous” peace treaty Lenin and Trotsky signed with Germany at Brest-Litovsk. To appease the Germans, it was announced that Blumkin had been executed. Meanwhile Trotsky, who had taken him under his wing, sent him to Ukraine to carry out sabotage missions behind White enemy lines. A year later Blumkin resurfaced in Moscow, where everyone had thought him dead. Far from hiding, he showed up at soirées and hung out in fashionable literary cafés. One evening he ran into the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who took him in his arms and shouted, “Zhivoi!”—“He’s alive”—a nickname that stuck.

I sat down on the trunk and used my phone to search for Blumkin. A series of photographs appeared. I clicked on the first one: a bearded man with dark eyes surrounded by a group of Jewish merchants. The caption read, “Blumkin in Jaffa, 1928.” In another he is dressed like Lawrence of Arabia and posed atop a camel in front of the Egyptian pyramids. In a third, he is walking on the Tibetan plateau. The caption relates to the Roerich expedition: “Searching for Shambhala, 1925.” In yet another photo, I recognized the poet Sergei Esenin’s baby face and somewhat feminine blond curls. Nearby, a leather-jacketed Blumkin seems to be watching over him. And there is Trotsky’s train: on the platform, the Old Man is raising his cap and saluting the crowd in front of a huge red flag that fills the left third of the photograph. Dressed in a Red Army uniform, Blumkin stands on the train steps, scrutinizing the faces around him. The last photograph had been taken in 1923 in the Gilan Mountains in Persia, according to the caption: a group of fighters surrounding a man, apparently their leader, his head wrapped in a bloody bandage.

Was it the same man in all these photos? It was hard to say, as his appearance changed from one shot to the other. Sometimes his face looked angular; sometimes puffy. In some pictures he looked about twenty; in others, forty. Yet the dates of the photos left no doubt, as only about a decade separated the oldest photographs from the most recent: 1918–1929. This was indeed the same Yakov Blumkin, alias “Zhivoi,” alias “the Lama,” alias “Sultan-Zade.” A Google search yielded 3,300 hits, which rose to 16,700 if the search was done in Russian, some of which I could understand thanks to translation software. This was a far richer database than the one at my disposal when I started my research at Nanterre’s Bibliothèque de documentation internationale contemporaine. In the early 1980s I had spent entire days there, finding only a few lines, and sometimes just a footnote, that as often as not referred to the same episode, the most famous one in Blumkin’s life: the assassination of the German ambassador in 1918.