PROLOGuE

If you keep coming around here little girl people will begin to think you’ve taken a liking to Matthew Strong. I guess there are worse things than befriending an old man like me. But you don’t seem like the sort of person who’d concern herself with what others say about her. Tell me something. How come you out here by yourself?

Oh, I see. These cats sure are cute. You got your eye fixed on one of them? Her? Why don’t you pick her up and bring her closer so I can get a better look.

Yes, she’s a pretty one indeed. I like ginger and white as well. Matter of fact, now that you got me thinking about it, I do recall seeing another cat just like her. They like to congregate out here near this abandoned shack.

I wasn’t born with bad vision. In fact, I had about the best vision of any of the white or colored boys I used to play with when I was a kid. When them boys were waiting while their fathers weighed the cotton, they’d come out to where I’d be, pump gun on my shoulder, tin cans on a stump and a few dangling from a fishing line tied to a birch branch. I’d tell ’em they could borrow my pump gun if they’d give me a penny, and they’d say, “Nah.” Then I’d cock the gun and shoot a pellet in one of them cans. I’d say, “Bet you can’t hit none of ’em.” They’d pull off their straw hats, making all sorts of bold claims. I’d laugh and bet ’em a dime they couldn’t hit not one of ’em. Got ’em every time. I must’ve earned me ten dollars over the years.

You like stories? Me too.

There was this old Negro who worked on my daddy’s land used to always say, “Truth is buried within those tall tales old folks tell. You just gotta take the time to untangle them.” But most young people these days ain’t got no patience to figure out any of the stories I tell whether they’re true or not.

I’ve learned over the years most people have a hard time accepting what’s true even when it smacks them on the back of their head. But a man got no problem believing a pack of lies. Especially when he don’t have the courage to make amends for his sins, and the lies he tells to justify ’em.

What’s that? Time for you to go home?

You right. Bet your grandma be worried with you out here by yourself. Now, remind me again what you said your name is?

Oh, yes, Odessa, that’s right. A beautiful name for a beautiful girl.

Before you go, you mind doing me a favor? Think you can help me find my brown leather book where I keep my stories? I dropped it somewhere in this shack when I was feeding them cats. My vision ain’t so good no more.

You see, that leather book is where I keep those tall tales this old Negro used to tell me when I was a boy. You think you have time to listen to me read one?

Whichever one you like. Don’t make a bit of difference to me. Maybe something short? It’ll be dark soon. No telling what’s in these woods.

BOOK I

PRESENT DAY

My name is Allegra Douglass. I am one of the survivors.

My story may make you angry. Not necessarily at me, but about the reason things happened the way they did. Only looking back can I put the pieces together in a coherent manner, or at least in a way that makes any sense at all.

As a philosopher, I am drawn to problems. I’m fascinated by the relationship between ideas and actions; ideas behind our motivations; ideas beneath our fears. Some ideas, however, take you down paths best left unexplored; ground best left undisturbed.

Many newspapers, publishers, and magazines begged me to tell this story. But I have no desire for the media to frame my story as one of race redemption or progress from the days Klan night riders paraded openly down Sixteenth Street in Birmingham.

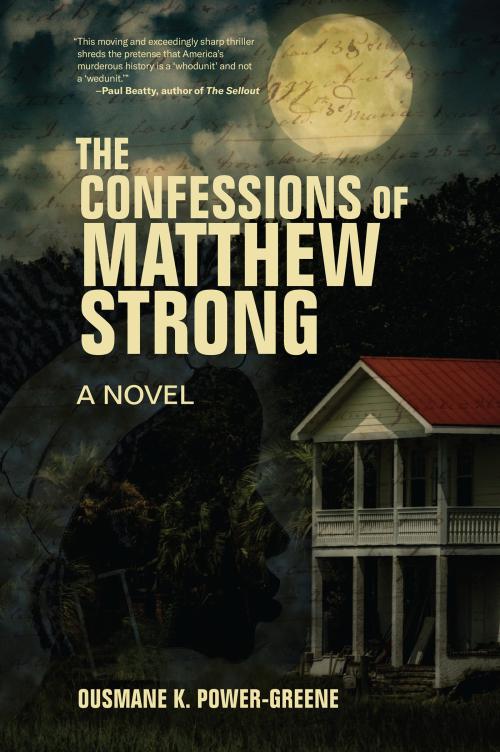

I refused to allow them to exploit the kidnap and torture of black girls. I wouldn’t tell them what Matthew Strong confessed to me when I was trapped in that plantation home and forced to write his white supremacist mission to redeem the South. I refused to make him more well-known than men like Charles Manson or let him go down in history as some modern-day Nathan Bedford Forrest.

At least, that’s what I told everyone who asked. But what is the truth? The truth is that I feared having my name forever associated with Matthew Strong. And I feared, after people read my story, they would sympathize with his mission even if they deplored his methods.

And this was exactly what he wanted.

There are those who never believed I’d remain steadfast in my determination to withhold my story from the public. Some assumed when I finally accepted what happened I’d be ready to speak. Others shadowed my posts online, waiting like dogs for me to toss a bone, trying to anticipate when I would break my silence.

One thing is for certain: all the talk in the world won’t change anything.

So why have I decided to tell you this now?

Maybe it’s because of something my grandma used to say: “Let your faith be greater than your fear.” Of course, she meant this from a Christian perspective, an entire system of beliefs I had abandoned when I entered college. I may still question the whole “Jesus died for your sins, on the third day he was resurrected, he ascended to heaven, and will come again to judge the living and the dead” thing.

But now I find St. Paul’s claim that “faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” to be a guiding principle. Maybe my fear has forced me to have faith that what I say will change the course of events unfolding just how Matthew Strong said they would.

Ever since I was liberated from the plantation home where Matthew Strong and his men held me and eleven other black women and girls, whenever I hear a southern accent, memories of my abduction return like mosquitoes at sunset hovering over my arm, darting through my fingers, daring me to slap so they can laugh and dash, laugh and dash.

That’s how my memories come back to me. The first time after I heard a man’s voice at my favorite coffee shop, another time when I came out of my apartment and stumbled into a UPS delivery man.

Then, I’m there again, feeling my legs go numb, my mind distorted by whatever they drugged me with. I hear the man who said he came to protect me ask if I feel strange—the ends of his words clipped like he was speaking into a fan. I glance at him and his concerned face melts into a cocky grin. Now he’s laughing. They were all laughing, laughing, laughing.

Next, I feel them lift me through the air like a suitcase, before pushing me in the trunk. Keys click; the car engine revs. Windshield wipers slap against the glass, rapid beeping, then I black out.

When I woke, I had no idea how long we’d been driving or where we were. Had we left Alabama? Were we in Mississippi? At one point we stopped and I had to go to the bathroom badly. I tapped the trunk with my knuckles. Silence. I was desperate. I banged harder. Finally, I heard feet crunching over.

“If you keep banging, we’re gonna have to give you more medicine. You wouldn’t want that, now would you?”

“I have to go to the bathroom.” There was a pause.

Then I heard a beep and the trunk opened. Two masked men stood over me, one with a drawn pistol. The other held a machine gun strapped across his back. I had pulled down my blindfold, but they insisted I put it back on before they lifted me out of the trunk.

“Where are we?”

They said nothing as they walked me across gravel to the bushes.

“Go here.”

“Can I at least take off my blindfold?”

I heard whispering, then I felt the barrel of a gun against my back as one untied it. I squinted, my eyes adjusting to the light. I pulled down my pants and squatted.

As I peed, I noticed a stretch of pine trees rising up a mountain range, but it was impossible for me to tell if we’d driven east to the Appalachian Mountains or south to the Oak Mountains. Think, Allie. One of them jabbed the gun against my back.

“Keep your eyes on the leaves or you’ll be pissing with the blindfold on.”

He surveyed the woods as if he feared someone would jump out and rescue me. Or was he trying to give me some respect? How ridiculous.

For a moment I considered running. But that’d be stupid. I had no idea where I was. They’d shoot me anyway.

I pulled up my pants and one took my arm and the other pressed his gun to my back again. I pleaded with them as the third one blindfolded me.

“Please. I’ll pay you. My husband and I have money.”

One of them laughed. I hated myself for begging, but I begged with all I had.

“Wait! Please!”

I shouted as they tied my hands behind my back and shoved me in the trunk.

TWENTY-FOUR DAYS BEFORE MY ABDUCTION

Two detectives—Detective Landers and Detective Kelley—showed up at my New York City apartment to ask about one of my only black graduate students, named Cynthia Wade. I offered tea, but they politely declined. Detective Landers put a banker box filled with books on my coffee table. He pulled a small spiral notebook from his front coat pocket and inquired about our relationship. I explained that Cynthia had left the program the previous fall, but she lived in my apartment building, so I still ran into her once in a while.

“And you two were close?” he asked, scribbling in his notebook.

I paused, wondering what this was about, wondering if they were investigating something Cynthia had done. There was a time in my life—fifteen years ago, perhaps—when I would have never let them into my apartment, let alone offered them tea. I thought about the detectives who used to show up at rallies posing as journalists, asking questions, taking down names. Then, a few days later, I’d find them sitting on the steps outside my apartment waiting to ask about someone they were looking for—a wanted activist, a former Panther, perhaps.

I crossed my arms. “Did she do something wrong?”

Detective Landers glanced over to his partner. “It seems a few weeks ago Cynthia vanished—phone’s turned off, no ATM withdrawals. Roommates haven’t seen her in weeks. One of them gave us this.”

Detective Kelley motioned to the box they’d brought. “Some books in here have your name written inside.”

I went through the stack, and noticed a copy of my latest book. I didn’t remember Cynthia borrowing it from me.

“And there’s that, too.” Detective Kelley motioned to an envelope in the box. I noticed my name and address. There wasn’t a postmark below the stamp.

“Did she collect your mail?” Detective Landers asked. His crew cut and pimpled cheeks made him look too young to be a detective.

“Sometimes. I used to have her stop by my apartment if I was away.”

They looked at one another again. Detective Landers came forward, his hands in his suit pockets. “So, this letter came for you, and she picked it up?”

“I guess so.”

I pulled the letter from the envelope. The investigators looked on, curiously.

Dear Dr. Douglass,

I have admired your work from afar for many years. Yet, this most recent book has misinterpreted the ideological roots of my cause. Me and others who have joined my movement are deeply concerned about how you misrepresented the noble design of men we deem true bearers of American democratic tradition. I look forward to the opportunity to speak with you in person about what you’ve failed to grasp despite a noble effort. It is my hope that the next time you find yourself in Alabama you will inform me and my associates so we may have the pleasure of conversing with you about these ideas and the relevance of your book for our current movement.

For the cause, William Shields, Esq.

When I glanced up, both detectives had positioned themselves so they could read the letter over my shoulder.

“Do you know this William Shields?” Detective Kelley asked.

I laughed. “No, this has to be some prank.”

“A prank? I don’t follow you.”

I shook my head. “You see, William Shields was a notorious white supremacist who led a reign of terror in Alabama after the Civil War.”

“I apologize, professor.” Detective Kelley folded her arms. “History was never my strongest subject. Rewind. You said this guy William Shields was some sort of racist terrorist in the 1870s?”

“That’s correct. Okay, let me put it another way.

You’ve heard of the Ku Klux Klan, right?”

“Of course.”

“Well, scholars believe William Shields murdered more black political leaders and white sympathizers than the Klan in Alabama until the federal authorities caught him in 1873.”

“What happened to him?” Detective Kelley asked.

“He was sentenced to death. But he did write a confessional, which chronicled his deeds and tried to justify his murders as an effort to ‘redeem’ the South after losing the Civil War.”

“Really? I never heard of this guy,” Detective Landers said.

“If you were from Birmingham, you would have. His father, Andrew Shields, was the wealthiest slaveholder in Alabama before the Civil War. After the war, he founded Birmingham Iron and Steel Company. Practically owned all mines in Jefferson County.”

“Is that where you’re from?” Landers asked.

“Alabama? Yes.”

“Like Cynthia?”

“That’s right.” I didn’t care for this guy. Did he actually think I had anything to do with her disappearance?

“Do you have any more questions? I really need to get some things done before I teach class.”

“Actually, yes. One more thing. Tell me, have you ever received a letter like this before?”

“A few since my book came out.” “What’s this one about?”

“The racial ideology of southern slaveholders.”

“Southern slaveholders, huh? Men like William Shields, I gather?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

Detective Landers pulled out his cell phone. “Would you mind if I scanned that letter? You know, just in case?”

“In case of what?”

“Professor Douglass, have you ever done one of those thousand-piece puzzles? The kind that sits on the dining room table terrorizing you to complete it every time you walk past?”

“Are you suggesting this letter is a puzzle piece that’ll help you figure out what happened to Cynthia?”

Detective Landers held out his open palm. I handed him the letter and he placed it on the coffee table to scan with his phone.

“I may not know where it fits”—there was a flash—“but I’m certain it’s a piece.”

Detective Kelley came over. “Thanks for your time and cooperation, professor. Please call us if you hear from Cynthia. Here’s my card.”

“Yes, of course,” I said, as Detective Landers tucked his phone in his coat pocket and returned the letter.