It’s not like we have never seen my father cry before. When you’re married to someone like my mother, who very often forgets everything around her, including her husband and her children and her dog, because she has become obsessed by the idea of making her own mechanical wristwatch and works twenty-four hours in one stretch to center the axles of the wheels while we children and our father go hungry—when you’re married to a woman like that you will have need to weep on the shoulders of close friends at least once a fortnight, which Father almost certainly has done in the company of Bent Piglet or John the Savior.

But he has never done it at home. On such occasions as we have seen Father weep, it has always been in church and on account of him saying something especially beautiful that makes him cry because he is moved and grateful for the Lord having provided Finø with such a magnificent pastor as himself. Or else he cries at a funeral in sympathy with the bereaved, and one must reluctantly admit that Father’s sympathy is almost as great as his satisfaction at putting it on display.

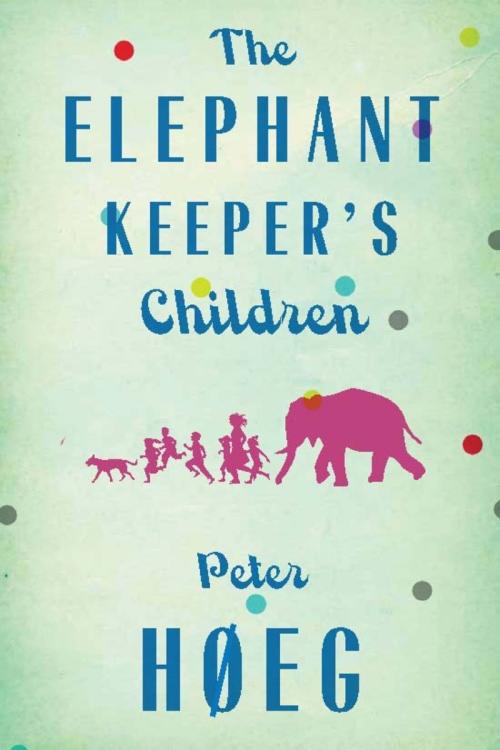

Though his complacency and sympathy both may be great, they have never been so great as what we now witness in the kitchen of our rectory home. What we see is something that has always been contained inside our father, but which only now is released, and to begin with we have no words for it. But Father leaves the kitchen and Mother goes after him, and Tilte and Hans and Basker and I remain behind and look at each other. We sit for a moment in silence, and then Tilte suddenly says: “They’re elephant keepers. That’s Mother’s and Father’s problem. They’re elephant keepers without knowing.”