In the interviews we often bring up the works of Karl Marx, which Duch knows and admires.

Me: “Mr. Duch, who are the closest followers of Marxism?” Duch: “The illiterate.”

People who can’t read are the “closest” followers of Marxism. They’re the ones who are in arms. And, I may add, they’re the ones who obey.

Those who read have access to words, to history, and to the history of words. They know that language shapes, flatters, conceals, enthralls. He who reads reads language itself; he perceives its duplicity, its cruelty, its betrayal. He knows that a slogan is just a slogan. And he’s seen others.

‘

In 1975, I was thirteen years old and happy. My father had been the chief undersecretary to several ministers of education in succession; now he was retired, and a member of the senate. My mother cared for their nine children. My parents, both of them descended from peasant families, believed in knowledge. More than that: they had a taste for it. We lived in a house in a suburb close to Phnom Penh. Ours was a life of ease, with books, newspapers, a radio, and eventually a black-and-white television. I didn’t know it at the time, but we were destined to be designated— after the Khmer Rouge entered the capital on April 17 of that year—as “new people,” which meant members of the bourgeoisie, intellectuals, landowners. That is, oppressors who were to be reeducated in the countryside—or exterminated.

Overnight I become “new people,” or (according to an even more horrible expression) an “April 17.” Millions of us are so designated. That date becomes my registration number, the date of my birth into the proletarian revolution. The history of my childhood is abolished. Forbidden. From that day on, I, Rithy Panh, thirteen years old, have no more history, no more family, no more emotions, no more thoughts, no more unconscious. Was there a name? Was there an individual? There’s nothing anymore.

What a brilliant idea, to give a hated class a name full of hope: new people. This huge group will be transformed by the revolution. Transmuted. Or wiped out forever. As for the “old people” or “ordinary people” they’re no longer backward and downtrodden, they become the model to follow—men and women working the lands their ancestors worked or bending over machine tools, revolutionaries rooted in practical life. The “old people” are the heirs of the great Khmer Empire. They are ageless. They built Angkor. They threw its stone images into the jungle and into the water. The women stoop in the rice fields. The men build and repair dikes. They fulfill themselves in and by what they do. They’re charged with reeducating us and they have absolute power over us.

The flag of Democratic Kampuchea (the country’s new name) bears not a hammer and sickle but an image of the great temple of Angkor. “For more than two thousand years, the Khmer people have lived in utter destitution and the most complete discouragement. . . . If our people were capable of building Angkor Wat, then they are capable of doing anything.” (Pol Pot, in a speech broadcast on the radio.)

How many people died on the building sites of the twelfth century? Nobody knows. But what they built expressed a spiritual power and elevation utterly absent from the creations of the Khmer Rouge.

‘

A few days before April 17, 1975, one of my father’s friends came to our house to warn him, “The Khmer Rouge are getting closer. You and your wife and children should leave. There’s still time. We’ll find a solution for you—a plane to Thailand, for example. You must flee.” My imperturbable father refused to budge. He wasn’t afraid. A man devoted to education, he was a servant of the state and had always worked for the general good. Once a month, in his spare time, he’d meet with some friends—professors, school inspectors—and proofread translations of foreign books into the Khmer language. He didn’t want to leave his country.

And he didn’t think he was in any danger, even though he’d worked for every government through the years.

Using the sequence of events in China as an example, he assured us he would no doubt be sent to a reeducation camp for a while; such an outcome seemed to him to be practically in the natural order of things. Then conditions would start to improve. He believed in his usefulness to the country, and in social justice. As for my mother and us, the children, the Khmer Rouge wouldn’t consider us important. That, then, was the analysis of an educated, well-informed man, a man with peasant origins to boot. In retrospect it’s easy to see the naïveté in his assessment. His viewpoint was, first and foremost, that of a humanist, a progressive who envisioned a humanistic revolution.

However, my father knew that some acts of violence had already occurred. Around the end of 1971 a schoolteacher had explained to him that teaching in the zones occupied by the Khmer Rouge insurgents was almost impossible. He spoke of extortion, torture, murder. They were pitiless, he said, and most of all there seemed to be nothing in their organization that was either egalitarian or free.

The popular revolution was cruel, but on the other hand Lon Nol’s regime was no better, with its trail of disappearances and arbitrary executions. The peasants would no longer put up with destitution and servitude. Their misery was increased by the American bombardments in the hinterlands. In the towns, too, the ruling power was loathed; in a climate of penury, corruption had reached intolerable levels. It was on this fertile ground of anger that the Khmer Rouge, with their discipline, their ideology, and their dialectics, had prospered.

My father had met Ieng Sary after his return from France in the mid-1950s. Ieng Sary had gone on to become an important Khmer Rouge leader, and then in 1963 he’d disappeared into the jungle with Pol Pot. At that time my father had helped his wife. Their children were in the same school as we were. My father couldn’t imagine this former pupil in the Lycée Condorcet, this student of Marx, this professor of history and geography, participating in an inhuman or criminal enterprise. He figured that the new regime would make educating the masses a priority. Basically he had faith in his own program.

The French protectorate of Cambodia had come to an end in 1953, but true independence is not so easily obtained. Under Lon Nol’s regime propaganda was everywhere. A climate of violence prevailed. Like all boys of my age I was fascinated by the rifles and the uniforms. Whenever a military truck approached our house, I’d station myself outside with a wooden gun. I drew tanks in my notebooks.

When I reflect on the situation, I feel certain that children in the countryside must have shared the same fascination, but the Khmer Rouge took them in hand very early, at eleven or twelve years old. They were given a uniform—black shirt, black pants, a traditional checkered scarf (a krama), a pair of sandals cut from tire rubber—a rifle, and, above all, an ironclad ideal and an iron discipline. What would I have thought if someone had consigned a weapon to me and promised a people’s revolution that would bring equality, fraternity, justice? I would have been happy, as one is when he believes.

‘

The fighting was getting closer to Phnom Penh. We could feel the earth shaking from the American bombardments: the famous “carpet bombing” strategy already employed in Vietnam. My country cousins had warned me that when the B-52s approached, I shouldn’t throw myself flat on the ground; the vibrations in the earth could give you ear- and nosebleeds, even at a distance of several hundred yards. They also taught me to recognize the whistling of rockets. They couldn’t take being hungry and thirsty and afraid anymore. Because of the air raids, they had to harvest their fields at night. They all died alongside the Khmer Rouge. That’s not hard to explain: the more bombs the American B-52s dropped, the more peasants joined the revolution, and the more territory the Khmer Rouge gained.

The refugees crowded into the capital. They seemed dazed. Rationing became widespread. There were shortages of water, rice, electricity, gasoline. We took in my aunt and her two children and lodged them on the ground floor of our house. We could hear the rockets whistling as they fell on our neighborhood, and then the mournful wailing of the ambulance sirens. My school was located across from a pagoda, so we witnessed, with increasing frequency, the cremations of officers who had died in combat. A general, impalpable atmosphere of anxiety pervaded the city. We were waiting, but for what? Freedom? Revolution? I couldn’t recognize anyone anymore—all faces were closed. It was then that I put away my wooden rifle. The party was over, and I had no ideal to aspire to.

‘

On April 17 my family, like all the other inhabitants of the capital, converged on the city center. I remember that my sister was driving without a license. They’re coming! They’re coming! We wanted to be there, to see, to understand, to participate. There was already a rumor afoot that we were going to be evacuated. People ran behind the columns of armed men, all of them dressed in black. They were young, old, and in between, and like all peasants, they wore their pants rolled up to their knees.

Many books declare that Phnom Penh joyously celebrated the arrival of the revolutionaries. I recall instead feverishness, disquiet, a sort of anguished fear of the unknown. And I don’t remember any scenes of fraternization. What surprised us was that the revolutionaries didn’t smile. They kept us at a distance, coldly. I quickly noticed the looks in their eyes, their clenched jaws, their fingers on their triggers. I was frightened by that first encounter, by the entire absence of feeling.

‘

Some years ago I met and filmed a former Khmer Rouge soldier, a member of an elite unit, who confirmed to me that they’d received clear instructions on the eve of the great day: “Don’t touch anyone. No one at all. And if you have no choice, never touch a person with your hand; use your rifle barrel.”

‘

Annotation in red ink in the register of S-21, across from the names of three young children: “Grind them into dust.” Signature: “Duch.” Duch acknowledges that it’s his handwriting. Yes, he’s the one who wrote that. But he clarifies his statement: he wrote those words at the request of his deputy, Comrade Hor, the head of the security unit, in order to “jolt” Comrade Peng, who seemed to be hesitating.

The pages of that register each contain between twenty and thirty names. Accompanying every name, Duch jotted a note in his own hand—“Destroy.” “Keep.” “Can be destroyed.” “Photograph needed.”—as though he had detailed knowledge of each case. The thoroughness of torture. The thoroughness of the work of torture.

‘

We went to stay with friends who gave us temporary lodging in the center of the capital. At an intersection jammed with vehicles, soldiers, and a crowd of people, a Khmer Rouge commander riding in a jeep with a pistol at his belt and a cohort of bodyguards around him recognized my father, put his hands together in greeting, and slowly bowed. Who was he? A former pupil? A schoolteacher? A peasant from my father’s native village? A few yards farther on my father said to my sister, “Let’s try over to the right,” but at once he received a violent blow to the temple from a rifle butt. “No! To the left!” a young Khmer Rouge yelled. We obeyed him.

When my older sister’s husband, who was a surgeon, saw what terrible shape the refugees were in, the pregnant women on the roads, the gravely ill abandoned to their fate, he left us and went back to the Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital. For days on end he performed operations and provided medical care, and then he was evacuated, together with all the patients. The chaos was indescribable. And there were no longer any means of communication—or rather communication itself was forbidden. My brotherin-law searched in vain for us and then set out alone for his native province. Fifteen years later I learned that he’d been arrested at Taing Kauk. Somebody recognized him and denounced him as a physician. At that time people would make denunciations for a bowl of rice. Or out of revenge. Or jealousy. Or to ingratiate themselves with the new power. A physician? He was executed on the spot.

About a year later his wife, my elder sister, disappeared. Both of them, she and her husband, had worked for Cambodia. What could be better than archaeology and medicine? The body of the past and the living body? My father had hesitated too long to send them to France, even though a grant would have made it possible, and even though he’d already succeeded in sending four of his children abroad. He wanted them to specialize, to make further progress, and then to come back and serve their country. But he gave up the idea.

When I go to the archaeological museum—the National Museum of Cambodia, a complex of red buildings with ornate, soaring roofs, built by the French—I think about my sister, who, despite her young age, was the museum’s deputy director. When I was eight or nine years old, I often went to visit her in her office. I’d climb up on the little brick wall and use a stick to knock down fruit from the big tamarind trees. The ripe tamarinds were delicious. Today I wouldn’t dare do that. Because of my age? Or my memories? The royal palace, with its high walls and its traditions, isn’t far. The world we knew will not return. And you, my sister, I never saw you again. I can still picture your colorful skirt when you would appear at the big, carved wooden door, and your bag filled with documents. I remember our walks together. Your words. And my caprices. I see you smile. You take my childish hand.

‘

Early on the morning of April 17, a soldier presented himself at our front door: “Take your things! Leave the house! Right away!” We sprang into action. Immediately, without knowing why or how, we obeyed. Did we already feel fear? I don’t think so. It was more like astonishment. One of our neighbors, a handyman who’d become a Khmer Rouge commander, tried to reassure us.

The whole city was in the streets. The men in black told us we’d be back in two or three days. The hunt for traitors and enemies had begun. The purge was hideous but classic in those circumstances. The Khmer Rouge were looking for army officers, senior civil servants, supporters of Lon Nol. According to a spreading rumor, the Americans were going to bomb the capital. The Khmer Rouge leaders had frequently alluded to the possibility of an American bombing, and then certain Western intellectuals had echoed the speculation. The Americans did nothing. Who could have seriously entertained the thought that they would bomb a city of two million people just a few days after withdrawing their personnel and ending their support? I still remember the helicopters evacuating their embassy. You needed a lot of hatred and a good deal of blindness, or some unspeakable other reason, to believe in that fable.

Each of us carried a bag prepared by my mother, with her innate practical sense, and we left in the car. We didn’t get very far. Before long we were lost in the human flood.

There were women and children pushing wheelbarrows, men carrying insanely heavy loads, people half-crazed— and everywhere the fifteen-year-old fighters, with their cold eyes, their black uniforms, and the cartridges in their bandoliers.

Historians today think that the revolutionaries drove some 40 percent of Cambodia’s total population into the countryside. In the course of a few days. There was no overall plan. No organization. No dispositions had been made to guide, feed, care for, or lodge those thousands and thousands of people. Gradually we began to see sick people on the roads, old folks, serious invalids, stretchers. We sensed that the evacuation was turning bad. Fear was palpable.

‘

I question Duch tirelessly. Although he looks the tribunal’s prosecutors, judges, and attorneys in the eye—he has a monitor in front of him and knows when he’s being filmed—he never gazes into my camera. Or hardly ever. Is he afraid it will see inside him?

Duch talks to heaven, which in this case is a white ceiling. He explains his position to me. He makes phrases. I catch him lying. I offer precise information. He hesitates. When in a difficult situation, Duch rubs his face with his damaged hand. He breathes loudly. He massages his forehead and his eyelids, and then he examines the neon lighting.

One day during a dialogue that’s turning into a fight, I see the skin of his cheeks grow blotchy. I stare at his irritated, bristling flesh. Then his calm returns, the soldier’s calm, the calm of the revolutionary who’s had to face so many cruel committees and endure so many self-criticism sessions. Then I stop filming him and say, “Think about it; take your time.”

He smiles and speaks softly to me, “Mr. Rithy, we won’t quarrel tomorrow, will we?” I see clearly that he’d like us to understand each other and laugh together. And he needs to talk to me. To continue the discussion. To win me over. No, he’s no monster, and he’s even less of a demon. He’s a man who searches out and seizes upon the weaknesses of others. A man who stalks his humanity. A disturbing man. I don’t remember that he ever left me without a laugh or a smile.

‘

We drove several miles and stopped. Should we go on? Where? A soldier walked up and, without a word, signaled that we should get moving again. My father sighed and clenched his fists. The scene was repeated twice more. The Khmer Rouge spoke a rather odd language, using words I knew little or not at all. For example, they used the verb snœur to confiscate our car, which they later left on the side of the road. Theoretically snœur means “to ask politely.” The word was smooth, almost soft, but the look in the eyes was violent. Thirty years later Duch evokes Stalin, “an iron fist in a velvet glove,” and summarizes the Khmer Rouge attitude this way: “courteous but firm.”

This way of speaking made us uneasy. If words lose their meaning, what’s left of us? For the first time, I heard a reference to the Angkar (the “Organization”), which has filled up my life ever since. We set out on foot, and then the sun sank behind the rice fields.

We were beginning to guess, from the tone and looks of the Khmer Rouge, that we wouldn’t be seeing Phnom Penh again anytime soon. And I don’t remember encountering anywhere the force, the joyful excitement, or the freedom of the first sansculottes.

‘

In M-13, Duch frequently attended interrogations. He reflected upon them. Observed them carefully. “I went so far as to derive a theory from them,” he tells me. I don’t understand this formulation. “Derive a theory from them? What theory? Explain it to me . . .” He replies, “I remained polite but firm.” Then he falls silent.

‘

The second night, my mother asked my father to go and throw away his neckties. The searches hadn’t started yet, but rumor had it that some young people with long hair had been executed and their heads paraded around on staffs. My father disappeared into the forest, ties in hand, and came back after hiding his former life.

‘

At dawn on the day after the fall of Phnom Penh, the prisoners inside M-13 prison, in the northern part of the country, received an order to start digging. Under the white-hot sky, sweating and suffering, they excavated a ditch. How many of them were there? Dozens? We’ll never know. They were executed. Nothing remains of those mass graves, some of which may have been immense. As the years passed, the Khmer Rouge planted cassava root and coconut palms, which have since consumed bodies and memory.

Duch reached Phnom Penh with his entire crew: several dozen peasants—a few as young as thirteen or fourteen— whom he’d chosen and then educated in the ways of torture. Duch’s team included Tuy, Tith, Pon, and Mam Nay, known as Chan. Some of these men were also former professors. Mam Nay had been in prison with Duch, his friend, his double. They both spoke French fluently, and they had an almost intuitive mutual understanding.

The new history had begun; the murderers were waiting in the outskirts of the capital. Soon they would occupy the former Ponhea Yat lycée, which would be known as S-21.

Later I show Duch a photograph of Bophana before she was tortured. Black eyes, black hair. She seems impassive. Already elsewhere. He holds the photo a long time. “Looking at this document disturbs me,” he says. He seems moved. Is it compassion? Is it memory? Is it his own emotion that touches him? He’s silent again for a while, and then he concludes, “We’re all under the sky. When it rains, who doesn’t get wet?”

‘

We adopted the habit of sleeping in the forest, not far from the road. We’d throw a plastic sheet on the ground and lie down on it.

Most necessities were unobtainable: drinking water, milk for the babies, medical assistance, fire. Prices skyrocketed. For my thirteenth birthday on April 18, my mother had bought a ham on the sly and had it caramelized. It must have cost tens of thousands of riels. We shared that dish, but I don’t think any of us smiled during the meal.

After a few days the rumor started going around that our currency wasn’t worth anything anymore, that it was simply going to disappear. Vendors started refusing to take banknotes. The effect was devastating. How could we eat, how could we drink, how could we live without money? Bartering had sprung up again as soon as the evacuation began, and now it was widespread. The rich became poorer; the poor stripped themselves bare. Money’s not merely violence—it also dissolves; it divides. Barter affirms what’s absolutely lacking and renders the fragile more fragile still.

My provident mother had brought away with us a quantity of sheets, which she exchanged for food. Those big pieces of fabric were very useful. My mother was able to obtain some mess tins, some American army spoons, a bucket, a pan, and a boiling kettle so that we could drink, risk-free, water from the Bassak River.

We came to realize that this trend was irreversible.

Years later I looked at some extraordinary archival photographs; they show the Central Bank of Cambodia right after the revolutionaries blew it up. Only the corners of the building remain, sad pieces of metal-reinforced lacework standing over rubble. The message is clear. There’s no treasure; there are no riches that can’t be annihilated. We’ll dynamite our old world, and thus we’ll prove that capitalism is but dust inside four walls.

A lovely program, worth a minute’s consideration. It’s often the case, in every country, that rebels call for a society without currency. Is it the money that disgusts them? Or the desire to consume that it reveals? Exchange is supposed to have unrecognized capabilities. Free exchange, which is the term used for barter. But I’ve never seen a free exchange. A gift is something else. I lived for four years in a society without currency, and I never felt that the absence of money made injustice easier to bear. And I can’t forget that the very idea of value had disappeared. Nothing could be estimated, or esteemed, anymore—not human life or anything else. But to assess something, to evaluate it, doesn’t necessarily mean to have contempt for it or to destroy it.

Nothing could be assessed anymore? Well not exactly nothing, because throughout that whole period, gold never stopped discreetly circulating. It had extraordinary power. With gold you could cause what had disappeared to appear again—penicillin, for example. Rice, sugar, tobacco. The Khmer Rouge were full participants in such trafficking.

Other archival images: the treasury. Nailed wooden crates, discovered in a warehouse. Inside, under sheets of transparent plastic, the official banknotes of the new country. So it seems that Democratic Kampuchea had its currency ready to circulate after all. What happened? Logistical problems? Further doctrinal radicalization? The new currency was never used.

We bartered what we could—in the beginning, exchanges of that sort were tolerated—but very soon, we had nothing left to exchange. Contrary to the popular notion, it’s not true that there’s always “something left” to swap. I’ve seen a country stripped completely bare, where a fork was a possession too precious to give away, where a hammock was a treasure. Nothing’s more real than nothing.

‘

I can think of few examples in contemporary history of a population transfer so massive and so sudden. What to call it? Organized exodus? Forced march? I don’t want to be told that the Khmer Rouge had no choice, that they were at war with everyone, that they’d just come out of the jungle, that they had no human or technical resources, that they did their best in a troubled time, or that it’s easy to be right in hindsight. I don’t want to hear that the Khmer Rouge acted as they did because they thought it would be a solution to the impending famine they claimed to dread the prospect of. Or that the American bombers were already circling over the capital.

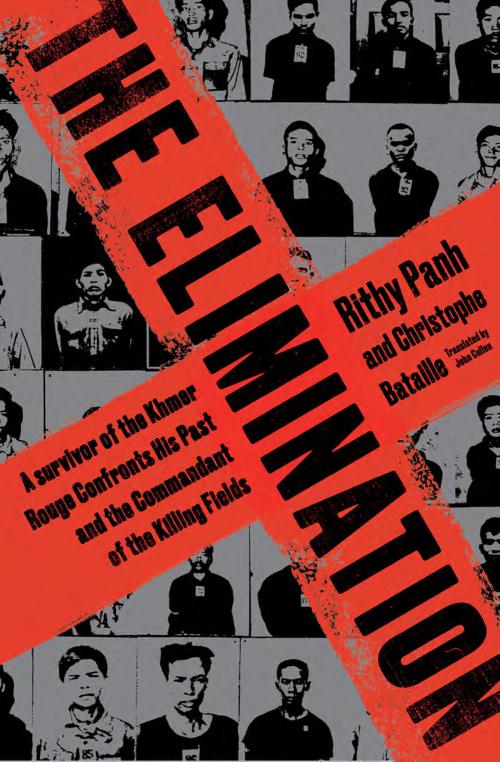

Unfortunately I can’t see in the “evacuation of Phnom Penh” anything other than the beginning of the extermination of the “new people,” namely—according to Duch’s own definition—“capitalists, landlords, civil servants, members of the middle class, intellectuals, professors, students.” The cities and therefore the universities, the libraries, the cinemas, the courts, and the administrative offices were to be emptied. Those centers of commerce, of corruption, of debauchery, of every sort of trafficking were to be emptied. Hospitals and clinics were to be emptied too. The evacuation of the capital prefigured the overall plan that we now know was in place.

The first political decision of the new order was to shake up the society: to uproot city dwellers; to dissolve families; to put an end to all previous activities, especially professional activities; to break with political, intellectual, and cultural traditions; to weaken individuals physically and psychologically. The forced evacuations took place at the same time all over the country, and no cities were excepted.

And so the complete overthrow of society began. Very quickly, as one may imagine, there were thousands of deaths and a great many sick and starving people.

Now let’s reason in the opposite direction. Let’s take as our hypothesis that the Khmer Rouge wanted to protect the inhabitants of the cities in general and of Phnom Penh in particular. Once the “political cleansing” (I don’t know what else to call that manhunt) and the American bombardments were over, why didn’t they organize the return of the population? It wouldn’t have been simple, of course, but tens of thousands of deaths could have been avoided. The hypothesis is, unfortunately, absurd. Why would the revolutionaries protect members of the class they hated? In fact, right up to the end, they never stopped undermining, starving, “forging,” and exterminating the “bourgeoisie.” The Khmer Rouge leaders’ overall plan was nothing if not consistent. And they got what they wanted: the almost immediate destruction of the middle class.

‘

Well before those events, I remember my father taking me with him to visit a woman who was very close to the revolutionaries. I called her Aunt Tha. She and her husband, Uch Ven, had studied in France and then returned to Cambodia. Shortly thereafter he’d gone underground