1

Nobody asked how she was dressed that morning, but she made a point of telling them anyway, that her white sneakers were the only shoes she had, that since dawn she’d been thinking about which skirt or jeans would suit the occasion, likewise which bright red lipstick to wear. She was sitting on the Univers Café terrasse on the big pedestrian square in the heart of the old city. Behind her, the words city hall in very big letters could be read on the high stone wall, higher even than the tricolor flag drowsing in the warm air like a sleeping guard. Soon she would pass through the wide gate and cross the paved courtyard that led to the château, or what used to be the château, as it had long since been turned into city hall, though she would say it was all the same to her. In her mind, it made no difference whether she was meeting the mayor of the city or the lord of the village. She felt the same agitation and the same tightness around her heart at going into the great hall, which she was entering for the first time, almost surprised to have the automatic doors open at her approach, as if she expected to see a drawbridge come down across the moats and be dealing with a soldier in chain mail instead of a black-clad security guard. That’s the way it is in this city, you would think the centuries had washed over the stones without ever changing them, any more than the sea did, which twice a day attacked them and twice a day gave up and retreated in defeat, like a dog with its tail down.

Laura was early of course, sitting at the café with enough time to have coffee and read Ouest-France, or not actually read it but skim the headlines and the color photos, lingering on the sports page just the same, wondering if there might be an article about her father, the boxer. At the age of forty, he had just won his thirty-fifth fight, and the local press couldn’t stop celebrating his longevity, not to say his renaissance. Yes, “renaissance” was the word they’d been bandying about now that Max Le Corre was back at the top of the ticket from which he had disappeared for a while. She would probably have smiled to see yet another photograph of him in the ring, arms raised, under a headline aimed at the future asking, “Will he walk on water again?” Then, noticing the time on her phone, she folded the newspaper, put two euros in the bowl in front of her, and stood up. She looked at herself one more time in the café’s big window, feeling certain, as she would say later, that she had made the right choice, the black leather jacket that showed off her hips, over a tailored wool skirt whose weft the wind barely brushed when she tugged at it.

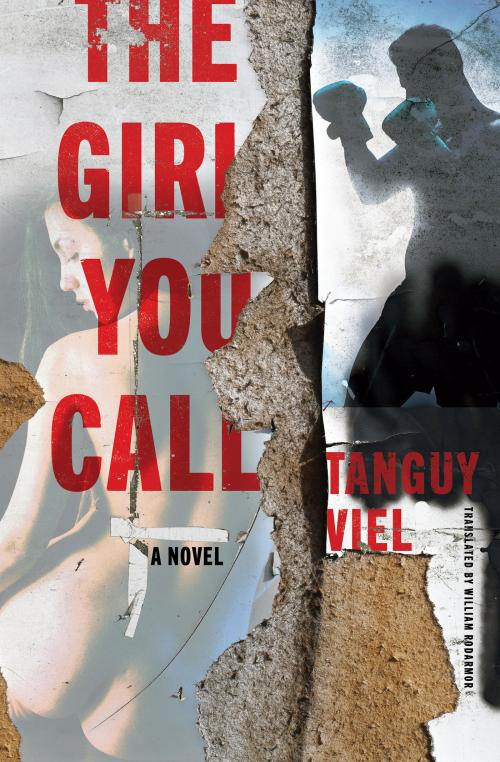

“Yes,” she told the policemen, “it might surprise you, but I told myself I’d made the right choice, along with the white sneakers everyone wears when they’re twenty, so you couldn’t tell whether I was a student, or a nurse, or I don’t know, the girl you call.”

“The girl you call?” one of them asked.

“Yeah, isn’t that what you say? Call girl?” She laughed nervously, having said “call girl” without raising a smile from either of the cops, one with his arms crossed, the other leaning closer to her, but both alert to every word she used, which they seemed to be weighing like exotic fruit on a grocery scale.

Laura picked up her story, about asking the guard at the entrance to city hall where the mayor’s office was, without knowing that he, the guard, would remain motionless and merely nod toward the big desk at the end of the hall, while almost automatically letting his eyes drift down her body from top to bottom. She was used to that, having men’s eyes linger on her, and had long ago stopped paying attention to it, for good reason. From countless earlier occurrences, she knew she was attractive, maybe because of her tall stature or her olive skin, but in any case she had long been aware of it, and was indifferent to whatever charm she was exercising that day, neither more nor less, with her tailored skirt that didn’t cover her knees, and the white sneakers that weren’t actually white anymore because of their scuffed leather uppers.

At the reception desk, she again said that she had an appointment with the mayor, feeling sorry that no one asked her the reason for her visit, to which she would’ve said that it was personal. “It’s true,” she told the cops, “I would’ve liked it if someone had asked me, just so I could answer, ‘It’s personal.’” But nobody asked the reason for her visit, not even at the top of the high stone stairway she’d been directed to, not even the birdlike secretary stationed at the office entrance like an old crossing guard. The woman displayed the appropriate censure or envy while staring at her, if that’s the right word, staring, her gaze this time falling like a guillotine from Laura’s head to her feet.

Said secretary sighed a little, like the housekeeper of a great house who feels entitled to judge her master’s visitors, then deigned to stand up and crack open a heavy wooden door whose passage she seemed to be guarding. She put her head in the opening and said, “Your appointment is here.” Laura heard a man’s voice answer, “Yes, thank you,” and the old secretary invited her to squeeze through the opening, that is, through the narrow passage she’d deliberately left between the door and the wall, as if Laura, the younger of the two, had to push her way in, at least that was the impression that stayed with her for a long time. “Yeah, it was something like that,” she said. “That I was the one who entered and not that I had been let in. But I swear I would have shoved her aside, if I’d had to.”

And maybe because of the suddenly dubious look from the policemen facing her, she felt she should add, “Remember, I grew up around boxing rings.”

They must have felt then that some part of her story lay in that sentence, pointing to the roughness of her childhood while hinting at the abyss that separated her from the man with the huge office, that nothing, neither the secretary’s cold greeting nor the outsized room, had any connection with her own world.

“No, nothing,” she told the policemen. “In a normal world we never would have met.”

“A normal world?” they asked. “What would you call a normal world?”

“I don’t know, a world where everybody stays in their place.”

And as she tried to imagine that world, normal and fixed, where everybody had a maximum range of motion, like a mechanical figurine, her eyes wandered to the blue cloth of the jacket of the cop facing her. Expressing a thought that rose from deep inside her, she said, “My father seemed so attached to that.”

2

Maybe I should have started this story with him, the boxer, since I can’t say which of the two, Max or Laura, justified it more than the other. I do know that without him, she would certainly never have gone to city hall, much less entered the mayor’s office like a budding flower, for the good reason that it was he, her father, who had asked for the appointment, first insisting on it to her and then insisting to the mayor himself, whose chauffeur he was. Max had been driving Le Bars around the city for the last three years, and they were beginning to know each other. The mayor was about ten years older than his driver, who flashed him a daily smile through the rearview mirror, or not really a smile but a perennial crinkling of the eyes. Max was forever trying to catch the eye of the man in the back, who often paid him no attention, instead looking at the slowly passing buildings and illuminated windows as if, because he was the city’s mayor, he owed it to sweep his gaze across all the buildings and the people on the sidewalks, as if they belonged to him. His being reelected a few months earlier, after virtually crushing his opponents in the first round of the election, certainly hadn’t helped foster a humility he already didn’t have in excess, or at least never made into a cardinal value, being more inclined to see his success as the incarnation of his own tenacity, coming up with words like “courage” or “merit” or “work” to drop at random into the thousands of speeches he’d given during the last six years at groundbreakings and in television studios. You could never tell how much of this stemmed from genuine conviction and how much from self-regard, because you always sensed he was gazing beyond his listeners’ heads, hoping his words might reach as far as Paris, where rumors were already circulating that he might be named a cabinet minister.

Max, who watched the mayor’s face in the rearview mirror every day, didn’t need a treatise on physiognomy to discern the drive and determination in it, under the heavy yet almost soft black eyebrows that contrasted so starkly with the cold, firm gaze that all powerful people have. In three years, Max had learned to follow its nuances and cracks, or rather not cracks but the deliberately allowed openings. If it’s true that power is based not in rigidity but in the calculated placing of its inflections, it was like Stockholm syndrome applied hour after hour, where each time Le Bars shed some of his austerity, it caused a false tenderness to bloom in the eyes of his interlocutors, drawing them in.

By that yardstick, Maxime Le Corre was a good customer, as far as I can tell, like a grateful horse whose bit has been loosened, especially as he was burdened with the added debt he felt he owed the mayor, who had hired Max when he was washed up—in the trough of the wave, as they say. Here is what happened in Max’s life: First, a wave had borne him on its crest like a graceful surfer, then brought him down in its darkening shadow tunnel. For years afterward, both the luminous years he’d enjoyed because of his talents as a boxer and the darker ones that overshadowed them like a stormy sky would rise to the surface in his memory, like cutout silhouettes on a spindrift-spattered windshield. He had hoped to drag a heavy wool blanket over those dark years and leave it lying there, because of the long night without boxing he’d gone through since the light of the rings went out, blinking on and off even worse than a coastal lighthouse. This is something all boxers know, that the ring is like a lighthouse whose flashes you might count from the deck of a ship when watching for danger, and that sometimes you don’t see the danger and get swept onto the rocks. This happens in boxing more than in any other sport: A boxing career has more striking chiaroscuros than a painting by Caravaggio.

When Max saw himself on billboards around town, he could hardly believe he was climbing back into the ring to box again, as he had in his glory days. Posters that sprouted like trees along the highways announcing the big bout on April 5 had photographs of the two boxers’ bodies set against a starry background, fists raised and muscles tensed—Max with his shaved skull and his eyebrows already focused on victory, seeming to defy the entire city with his anger and coiled strength, above fiery letters that read “le corre vs. costa: the Big challenge.” If you glanced at the poster and then at the man behind the wheel of the municipal limousine, you would have thought, Yeah, that’s him all right, same broken nose and battered eyelids, same shiny scalp, the same guy who in a few weeks would be challenging the other local man who had long ago stolen the spotlight.

“It’s getting close,” said the mayor.

“This time two months from now, I’ll be weighing in,” said Max.

“This is no time to gain weight,” the mayor remarked.

“Or to lose any,” answered Max.

They talked about his previous victories, the great pleasure the mayor had taken in handing Max the winner’s belt, the great pleasure, he said each time, in praising a real native, someone who trained right here, in front of the adoring audience, all so proud of the link that connected them to him, he who had always lived there, though in an unremarkable outlying neighborhood, some of whose glory was reflected in every window of every tower block where all the people lived whom he’d run into during his whole childhood, on benches in the squares, in elevators, and of course in the boxing gym whose heavy iron door they had pushed open at least once, and where they had all laced up gloves in the ring, imagining they were Mike Tyson for a moment. But of all the hundreds who had hoped in vain that some guy standing in the shadow of a column would see and notice them, the way an unseen god seemed to choose his prophets, only one had been lifted up, raised out ordinary life as it were, and that was Max Le Corre.

It didn’t take a genius to see the uncommon power in Max’s taut, heavy body, so it was also no accident either that one day a man in a white suit claiming to be a manager would enter the small gym where Max briskly dispatched his sparring partners and decide to take charge of his career, propelling him quickly to the national level whose title he would snatch. The trophy cup still reigned on Max’s mantelpiece, engraved with the words 2002 French Middleweight championship. Fifteen years later and already aged, Max was amazed to still read words like “renaissance” and even “resurrection” in the press. Resurrection was the other word he would sometimes see in the newspapers, and he disliked it as much as renaissance, because when the two words were deliberately used, they created the same vacuum sucking him toward the abyss that had preceded them.

To the mayor, he said, “If you’d told me I’d still be boxing at forty . . .”

“They say boxing is mostly in your head,” said the man in the back, still looking out the window.

His eyes on the road in front of him, Max pursed his lips ever so slightly, in a way that might mean, If I clocked you one, you’d see what it does in your head, but ever so slightly, so his silence was also acquiescence. The mayor was right, of course, boxing is mainly in your head, it’s a sport of nerves and mental strength, yes, that’s right, that was something Max wouldn’t deny.

“Anyway, it takes guts to face Costa,” the mayor continued.

“It’s now or never,” answered Max. “Time isn’t on my side.” And in this he was right, that boxing at his age, at least this is how he felt, was like skating on a frozen lake at the very end of winter. In spite of his victories, he wasn’t fooled by the thin coat of ice he was gliding across, still unafraid to cut the most delicate figures, but resignedly awaiting the day when the ice would suddenly crack and he would drown in the too-cold water.

“You’re going to win, Max. I’m sure of it.”

Taking advantage of this moment when the mayor seemed to be on his side, Max finally brought up the thing that been on his mind for days, which that very morning when he got up he had promised himself he would raise, and which had nothing to do with boxing, no, it was about his daughter, he wanted to talk about his daughter. “I’d like to ask you a small favor, Mr. Mayor, it’s about my daughter. She has moved back here and—”

“Sure,” said the mayor. “Go on.”

“It’s that she asked for an apartment from the city housing authority, but you know what it’s like, it takes time, and I figured maybe you could—”

To save him from floundering, the mayor cut the request short by saying, “Of course, Max. Tell her to come see me at city hall, and I’ll see what I can do.”

And as the car drove along the row of fully rigged tall ships like an open-air museum, Max heaved a sigh of relief, as if he had just left an exam room feeling that he had passed, even as he repeated to the man in the back that it was very nice of him to take the time to meet with her, that he didn’t have to do that, while he, the man in the back, busy straightening his tie or brushing the sleeves of his suit, answered that it was nothing, that in a way it was part of his job, that he had been elected for that, to help people. Max hoped that it would go well, that she would measure up. He said so later, Max did, that he had thought of that phrase. “Yes, it’s true, I hoped that she would measure up.”