A MEETING

Oscar, a Mexican writer whose name I did not recognize, contacted me on the Internet to arrange a meeting. He said simply that it was about my father. I was intrigued because my father had been dead for more than twenty years. We met in Paris, on the corner of rue du Temple and rue Dupetit-Thouars. He took four typed pages from his leather briefcase and handed them to me.

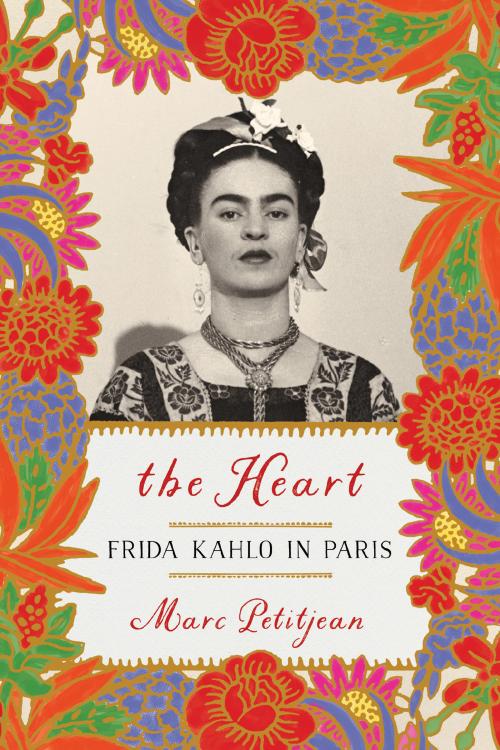

“So,” he said, “I wrote this article using the archives of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, and I discovered that your father had an affair with her when she came to Paris in 1939.”

I knew my father had known Kahlo and that she had given him a painting called The Heart, but he had never mentioned any sort of relationship with her.

Frida Kahlo is now seen as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century, and she has achieved icon status in Mexico; I was well aware of that. But what really happened between her and my father?

Oscar’s piece provided a little information about how the lovers met and the three weeks they spent together, and referred to some letters written by my father after Kahlo left. My Spanish is not good so I did not understand everything, but I felt that the author had overplayed things, using scant material to speculate about the intensity of the relationship. Most likely, no one would ever know what they actually experienced, but I still felt their connection must have been fairly powerful or unusual to justify Frida Kahlo’s gift of one of her paintings.

I saw Oscar again before he returned to Mexico. We met at the café Zimmer on the place du Châtelet, and I asked him why he was interested in my father. He explained that the idea of this affair appealed to him and he wanted to know more about the artist’s time in Paris in 1939. He was convinced that my father had received letters from her, and he hoped that I would pass them on to him. But I had found nothing apart from a telegram sent from the ocean liner Normandie when Kahlo sailed from Le Havre. It said, “Thinking of you so much Michel.” Oscar’s curiosity kindled my own, and I in turn embarked on researching the lovers’ lives.

When he met the Mexican artist in 1939 my father was twenty-nine and she thirty-two. He was an ethnologist, agronomist, left-wing militant, and journalist who moved in artistic social circles. Twelve years elapsed between their meeting and my birth—five of them war years. I realized that by revisiting my father’s past I might discover another person, very different from the man I had known; younger, of course, but with all the hopes, opinions, preoccupations, and commitments of his era, on the eve of the Second World War. The author Claude Mauriac described him in his memoir as a “cheerful bumpkin” with a funny, charming, baby face. The man I knew was certainly charming and elegant but also a little depressed and not especially amusing.

I thumbed my way through books devoted to the life and work of Frida Kahlo, looking for known facts about her time in Paris. The main biographies that I read attached little importance to this Parisian episode: thirteen pages, for example, in Hayden Herrera’s book that runs to more than five hundred pages and is the best-documented work to date. Several authors described Frida’s trip to Paris by drawing almost exclusively on the three letters she sent to Nickolas Muray or to friends; letters in which she is very critical of the French, whom she found boring and pretentious—probably with good reason, but it would be nice to know more.

I remember the painting The Heart hanging on the wall in the living room when I was a child. It was small and eye-catching, framed in faded red velvet. The image disturbed me for a long time with its stark depiction of a huge, bleeding heart lying on the sand, and a woman with no hands whose body is pierced by a metal rod and whose eyes seemed to stare at me. I felt a sort of vertigo if I looked at it for too long: I was afraid I would topple right into that terrifying world. It was only later, when my adolescent self could identify the painting with the eccentricities of the surrealists, that I started to like it.

When I asked my father what the painting meant, he told me what the artist herself had said: the work has two names—Memory and The Heart—and represents Kahlo’s transformation. At the age of seventeen she had a serious accident that caused a lifelong disability. On the left-hand side of the painting are the clothes she wore as a girl; in the center the European clothing she was wearing at the time of the accident; and on the right the traditional Native Mexican costumes that she then adopted, with a full, long skirt hiding her injured leg.

When he talked about her his tone of voice expressed respect and admiration, but I also detected something akin to reserve. Perhaps he preferred not to say too much in order to preserve the mystery surrounding their passion.

Did she specifically want to give him this painting or did he actively choose it among others? Either way, The Heart set a seal on their idyll.

On closer inspection, the painting feels more complex and dramatic than my father implied; the magenta velvet frame is reminiscent of Mexican votive offerings. The female figure at the center of the painting (a figure that represents Frida Kahlo) has a hole on the left side of her chest, where her

heart should be. A fine golden rod pierces diagonally through this gap. Tiny angels sit astride the two ends of the rod, using it as a seesaw. The face is serious, stares directly at the viewer, and has large tears rolling down its cheeks. The figure has no hands, and one of her feet, which is injured and stands on the sea, looks like a boat. She is positioned at the intersection of a symmetrically divided background: the upper half shows a blue sky filled with ominous clouds while the lower half is divided into two equal sides. To the left is a desert-like landscape with echoes of the background in the Mona Lisa. A huge heart lies in this landscape, with blood pouring from its severed arteries and flowing toward the sea on one side and toward the mountains in the distance on the other. The right-hand side of the lower half represents a desultory sea.

On the left-hand side of the painting and slightly set back, a red thread hangs from the upper edge of the frame and is tied to a coat hanger holding a girl’s school uniform of white blouse and blue skirt. A bare arm—which is intriguingly the outfit’s only arm—reaches toward the central figure. To the right of the portrait of Frida Kahlo, another outfit hangs in the same way: a red sleeveless top with gold patterning and a long green skirt with a white flounce. The single arm emerging from these clothes is linked through Frida Kahlo’s handless arm.

The image implies that some tragic event has taken place: blood flows, nothing is where it should be, and there is a general sense of instability. Frida Kahlo’s face expresses both acceptance of the situation and remote awareness of the event. The rigorous composition reinforces the impression that everything is frozen and cannot move forward. The clothes are suspended like miners’ workwear in a hanging room. The pain is so intense that the central figure is derealized and dismembered: her hands no longer belong to her, and her heart—a vital organ that is usually hidden and is the symbolic seat of emotions—is starkly exposed for all to see and disconnected from her body.

What did my father know about Frida Kahlo when he met her? Probably not much, like most people in Paris at the time. In 1930s Europe she was not known as an artist; she was Frida de Rivera, married to the internationally renowned muralist Diego Rivera. She was the “artist’s wife.”

When Frida and Diego married in 1929 she was eighteen and he twenty years older. Standing six feet one and weighing 330 pounds, with an intense face, bulging eyes, and an impassioned, unpredictable personality, the “ogre” was as attractive as he was frightening. Their relationship was tempestuous, passionate, extravagant, and painful, but Frida always put Diego first whatever the situation and she swore her admiration and unbounded love for him till the end of her days.

In 1933 she discovered that Diego was having an affair—and probably had been for the last two years—with her sister Cristina, with whom she was very close. This first infidelity of Diego’s, which was followed by many others, profoundly affected her trust. Devastated by the pain, she left for New York, cut her hair, and replaced her traditional Mexican clothes, which Diego dearly loved, with fashionable first-world outfits. This was how she chose to mark her breakup and her independence.

In The Heart she alludes to three periods of her life: on the left-hand side of the painting hang the schoolgirl’s white blouse and blue skirt that she wore when she met Diego. The central figure of Frida, with her short hair and modern clothes, represents her as an adult at the time when she realizes that Diego is cheating on her with Cristina. On the right is the Tehuana costume that characterizes the wife emotionally attached to her Mexican identity. The ripped-out heart lying bleeding on the ground expresses her pain. The boat is a reference to the orthopedic shoe she had worn since contracting polio as a child; the metal rod represents a rail that impaled her during a trolley car accident. The painting can, however, also be read as a form of forgiveness, because the Frida of the Mexican costume—which Diego so liked—is arm in arm with the angry Europeanized Frida.

The Heart brings together elements of the major events in the artist’s life: her childhood polio, her terrible accident, and Diego’s chronic unfaithfulness.

In my hunt for traces of Frida Kahlo, I found a box in the cellar full of letters and papers gathered together after my father’s death in 1993. I still hoped to find a letter from her, but in vain. The bulk of this paperwork was his correspondence with art historians regarding interviews he granted them, and with conservators from museums abroad to whom he lent the painting. I arranged the letters by date to establish a chronology of the painting’s history, and then wrote to everyone who had corresponded with him in the hopes of learning a little more about him.

The truth is, it now occurred to me that I knew very little about my father’s life.

Is there a place somewhere where the memories of all the dead are kept together? We can remember our own experiences at our leisure, but not other people’s. This hypothetical memorial reservoir would help me sketch a picture of my father in his earlier years. In the absence of such a resource, I am left to imagine things, drawing on facts, witness accounts, snatches of information and memories, giving me free rein to conjure a character who may be something like the man he truly was.

I picture my father as a young man, sitting in his shirtsleeves on the edge of a bed and looking at The Heart by the glow of a bedside light. Then he takes a pad of writing paper and writes one of the letters that Oscar will later find in the artist’s archives in Mexico:

April 7, 1939. Paris is gloomy, the fine weather has tried a few times, with no success. The atmosphere here is terrible and everything reeks of war, even my optimism is starting to crumble………………….. I haven’t forgotten you, I still stop and gaze at your painting for long stretches of time. I don’t understand how you were so kind to a poor ‘average’ sort like me. I send you lots and lots of kisses, that’s how much I love you. With my love, Michel.