One

I could hear him entering the office with his usual gusto. As always, I took a deep breath when my father came in. He stopped at the reception to get the latest messages, then asked, “Has anyone called?” With small, quick steps thumping the ground, he walked past my room followed by his secretary, to whom he was already dictating letters concerning the day’s court hearings. He was wearing a dark suit with a well-ironed white shirt and a black tie and carrying his heavy black leather briefcase. Then he doubled back and peered through the open door to my room. He saw me looking over a map covered in cobweb lines and asked accusingly, “What are you doing? Don’t you have any work to do?” Before I could explain, he had darted into his office to resume dictating.

I stayed in my office, examining the new 1984 military order plus the attached map that my father had seen me with. Road Plan Number 50, as it was designated, was the blueprint for the Israeli occupation authorities’ long-term objective of creating a new West Bank road network that was bound to have a devastating effect on the Palestinian landscape, on traditional towns and villages and agricultural areas. Studying it, I could see where future roads were to be built, how the existing network of roads was to be altered – from a north–south to an east–west grid – and how the Jordan Valley was to get a new road, one that would better connect it to Israel and consolidate it as the country’s eastern border. The implications were massive.

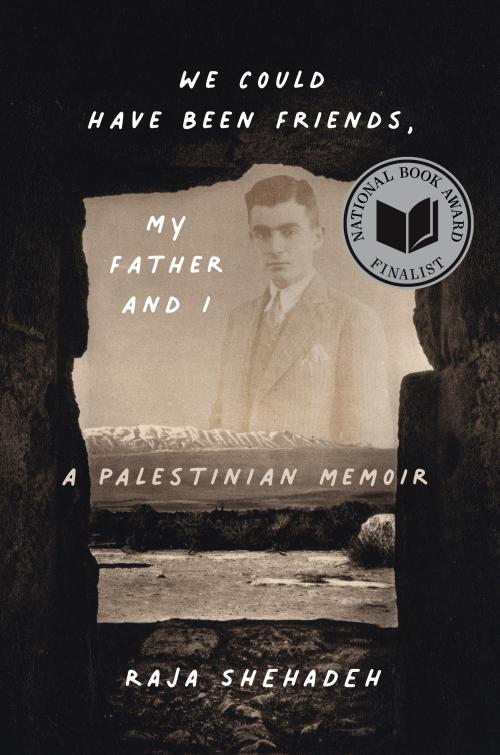

I gave my father time to finish dictating his letters, then I walked over to his office to show him the new order and map, which had only arrived in the post that day. When I suggested to him that we should submit objections to the proposal, he was not enthusiastic. He didn’t seem to share my sense of foreboding about the impact that the order would have on the land. The phone rang and he answered: “Aziz Shehadeh here. How can I help you?”

Waving me away, he sank into a conversation with his client. But I continued to think about the new Road Plan. A few weeks earlier I had taken a solitary drive down what we then called the Latrun Road, since it linked the hilly town of Ramallah to the coastal city of Jaffa via the Latrun Monastery. On both sides of the road I could see terraced hills dotted with olive trees in full leaf. The trees on the slopes of these undulating hills were all approximately the same height and they were all olives. As I drove northwest, the hills were awash with sunlight and the trees cast their shadows over the brown earth all the way down to the wadi.

On the hill to my right was a plot that belonged to my client. He had just heard that the occupation authorities had expropriated it and were planning to establish Beit Horon and settle it with Israeli Jews. I couldn’t understand why. What was the point of putting Israeli civilians in the midst of our hills, so close to a Palestinian village? How would these settlers get their electricity and water? They couldn’t depend on the inadequate services from the nearby village. Could they possibly have plans

for an alternative infrastructure? It was then that the worrying thought struck me like lightning: what if our Israeli occupiers, who already had total control of the networks serving us, were proposing to construct a superior network for water, electricity and roads connecting the settlements to Israel? That would mean they could cut us off without affecting their own people. We would be completely at their mercy for essential services. When I saw the military order announcing the new Road Plan I feared that the Israeli military was taking the first step to prepare the way for this eventuality.

We called these hills jbal (mountains), because we didn’t know any better. We had no mountains round about and thought that’s what our rolling hills were, for that was how they appeared to us. There was much then that we didn’t know. How could we have imagined that in these remote locations new settlements would be established that would sweep away the olive groves, changing the entire character of the area we knew and replacing our terraced hills with a concrete landscape, row upon row of uniform houses and straight, many-laned highways, as had already occurred in other parts of the Occupied Territories? Before 1967, the West Bank under Jordan was an impoverished, underdeveloped place. To build a single house was a big project that took a whole year to accomplish. The idea of taking over an entire jabal, building houses for a settlement and managing to supply it with water and electricity, was beyond us. The most we were able to build were single round stone structures that we called qasrs (castles), because they appeared to us like castles rising in the midst of the hills. They took their water from the nearby spring; there was no running water, no electricity and certainly no connection to a paved road. Water was scarce even within the confines of our existing cities. Every house had to have its own cistern for collecting rainwater to supplement what arrived irregularly through municipal pipes. To manage to bring water to remote areas was unimaginable.

A week after my first look at the Road Plan, I happened to be driving on that same road when I saw down to my right huge excavations: scores of olive trees that belonged to the residents of the nearby village and provided their main source of income were being uprooted. A new road was already being dug in the hills to replace the narrow, winding Latrun Road, which had been there from the days of the First World War and, like all our other roads, followed the contours of the hills. Now that I had seen the latest military order I felt certain that this new road was part of the comprehensive, alternative road network that the occupation authorities had devised. I knew we should waste no time in submitting legal challenges to try to stop the Israeli plan.

Over several days I tried to convey the urgency of the matter to my father and to express what I thought could be the impact of this new order. He listened, but I couldn’t get him to share my concerns. However, I was relieved that he didn’t stand in the way of my determination to challenge the Israeli military.

At thirty-three years of age, I had been a lawyer for five years but I still relied on my father’s counsel and his superior legal knowledge. He directed me to the laws I needed to consult. He was the unrivaled expert on land use and planning legislation. His initial view was that the law did not permit the Central Planning Authority, which was now staffed by Israeli officers, to devise a comprehensive Road Plan for the entire West Bank. In other words, there was no legal basis for the road map attached to the military order.

“The first law that you should study is the 1965 Jordanian Planning Law. It is still applicable. There you can find the different categories of roads and the procedures for challenging each one. Now go and study, and leave me alone to finish my work,” he instructed me, without moving his eyes from the documents he was reading.

I made a start immediately.

I found that my father was, as always, right. According to the Jordanian Planning Law, the Central Planning Authority had no power to devise a comprehensive Road Plan for the entire West Bank. This made the plan inconsistent with local law, which outlined the process for building individual roads but did not provide any legal basis for producing a single overarching plan. The proposed network would turn everything upside down. It would also wreak havoc on the landscape, replacing the narrow roads that followed the contours of the hills with wide, many-laned highways. It was clear to me that the new plans were not for the benefit of the local Palestinian population, as the law required. The main objective was to minimize travel time between Israel and the Jewish settlements, thus making them more attractive for Israelis to settle in. The more I looked into it the more I appreciated the enormity of the matter.

Further study of the 1984 Road Plan clarified many other issues that had mystified me, such as why the Israeli planning authorities adamantly refused to grant building licenses for certain structures that fulfilled all the necessary requirements, and why they rejected perfectly proper and meticulously produced plans for the expansion of towns and villages using improper, fake technical objections to justify their stance and stop the plans being implemented. From what I could see from the Road Plan, the rejections had been issued because these structures and the proposed zoning for expanded Palestinian towns and villages went against the vision for the area conceived by the Israeli planners, who were allocating the largest part of the land for future Jewish settlements. The Israeli planning authorities, staffed since the early 1980s by right-wingers committed to the political vision of Greater Israel, didn’t want anything to stand in the way of their long-term schemes. The map attached to Road Plan Number 50 was the foundation of all the land use planning that would ensue. By consulting this map, I learned of Israel’s vision for the West Bank. It was all there in the cobweb-like network of roads traversing the territory from east to west and along the Jordan Valley. It was imperative that we did all we could to block it before the plans became a reality.

First, we had to encourage local farmers whose lands would be affected to submit objections. However, although this might force the Israeli authorities to change the route of individual roads, it would not make them cancel the whole plan. Something more had to be done.

I went to consult my father and told him what I had come up with. He was silent for a while, thinking, then he said, “You’ve missed the most important point. International law does not allow an occupier to make long-term investments in an occupied territory. Clearly, with this plan, that’s precisely what Israel is doing.” He looked up at me with his winning smile.

Agreeing that this was a crucial point I had missed, I was keen to start writing a legal brief immediately, putting down all these objections to the plan. But did he really think there was any possibility of drawing up a convincing case against the plan under international law?

“More study will be needed before we’re ready to do that,” he said.

I mentioned that I had been reading about Namibia’s struggle for independence and the significance of the opinion given by the International Court of Justice at The Hague on a question submitted in 1970 by the Security Council of the United Nations. “Could we possibly interest the Security Council and ask them to formulate a request for an opinion from the ICJ on the legality of the Israeli Road Plan?” I asked.

My father always enjoyed the challenge of a new legal question and I could see his eyes lighting up at my suggestion. When I left his office I noticed that he was getting up and walking towards the shelf across from his desk, where he kept the references on international law, to begin the research for this new legal approach.