PRELUDE

Leipzig, April 22, 1789

Overture

I came to Leipzig, lost, in search of a sign.

What did I hope to find? Some manner of guidance from a dead composer? A message left behind among the living? Or some other sort of contact floating in the air, awaiting someone adrift like me, someone who had not even been born when that musician expired, not far from where I now stand, in this very city?

So absurd and desperate a quest could not be communicated to those who care for me, least of all to Constanze, who would have seen it as more evidence that I was unhinged, harrowed by debt, and sliding into melancholia. King Frederick requires me in Potsdam, I told her, he will award me a post that will solve all our problems.

Though nothing of the kind was true. As Leipzig was on the route to Potsdam, she would not find it entirely strange that I should stop here, offer a concert, replenish my coffers for a while, bring her back a pittance. Impossible to tell my loving little wife that I expected a whisper from God or somebody else to visit me.

One last chance before I must depart. For the third time in three days, I stand again in front of the grave next to St. John’s Church where Johann Sebastian Bach lies—six paces from the south corner of the building. It was almost forty years ago that he last saw the light, saw the light and lost it, was twice blinded, and then, and then . . . What happened then?

Of all those who know the answer, of the three men who may have known it, none is alive today. Only I remain, only I have an inkling as to whether it was a crime or an act of absolution that night, what door was opened—or did it close forever?—in the room where the great composer took holy Communion as he lay dying, only I can bear witness, trying to puzzle out the truth, separate falsehood from its illusions, only this ailing man of thirty-four who stares at that unspeaking grave, myself calling out to the man who brought me here.

The friend I will never see again.

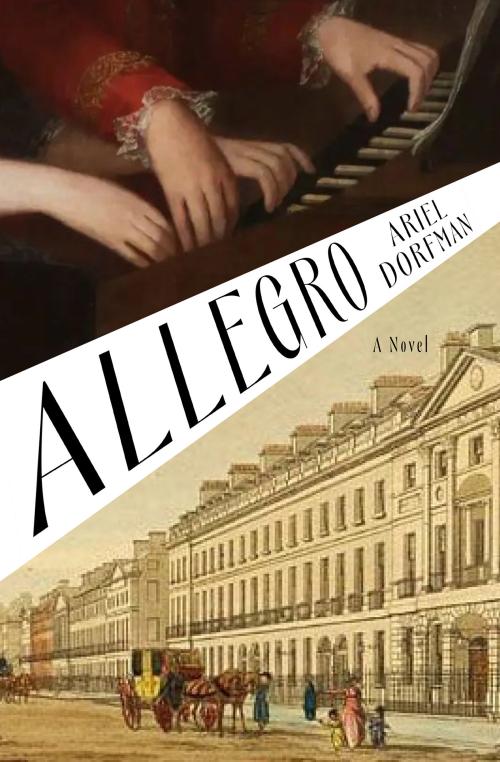

Part One

LONDON

FIRST CHAPTER

London, February 2, 1765

Allegro Ma Non Troppo

The man approached me barely a few seconds after the concert had ended, before the applause had died down. And yet his voice had a piercing, flutelike quality that carried above the clapping and the murmurs and the chatter—and indeed he was thin as a reed himself, and rather ungainly, but not unpleasant, an agreeable voice that might sing well if given the festive occasion. And he must have had many such occasions, because his forty-some years had clearly seen cheerful times, as a sparkle in his eye attested and his sumptuous attire confirmed, no matter how miserable an expression he now wore. But that was not what really called my attention.

“A word with you, young master,” he said, in a manner most bold.

He was addressing me in my native German tongue—everything correct and grammatical and in its orderly place, laden though the words were with the nasal, stilted accents of English vowels. Not dense enough to put me off, at any rate—I was such a child at the time, my ninth birthday celebrated a mere week earlier, and homesick to the bones. You will get used to it, my father had insisted, you cannot aspire to the sort of life you deserve, that the family deserves, if you and your sister do not travel widely, if you do not seek your fortunes beyond Salzburg. There were few people in London who talked to me in German, and my English was worse than rudimentary, despite my ability to imitate every sound I had ever heard—my French and Italian were already perfect! So even if he had not sported a forlorn and abandoned air, I would have listened gladly to the man who called me “young master,” and more so as he was filling my ears with flattering words about the symphony that had just now been exposed to a select audience in Carlisle House but soon would be admired by connoisseurs in the wide world who had not been privileged to attend the premiere of my princely recital, far better what you have composed, he assured me, than the offerings of Johann Christian Bach or Carl Friedrich Abel, that had preceded and followed my own divine harmony, that’s what he called it.

Though a mere whip of a boy, I had fallen into the habit of lapping up such accolades, all those adjectives, divine, majestic, invincible, all-powerful, which my own Papa frequently echoed, joining the river of praise that coiled around me, more, more, every superlative had been poured on my head like an endless baptismal fount and I desired more, I wanted that river to spill into an endless sea. And yet, and yet, the man was overreaching, he was magnifying my attributes beyond what even my own parents extolled, he may have meant every word but that was not the reason for his adulation. It must have been the way he smacked his lips as if he had just tasted the most delicious sauce, the way he let a smile break out as he genuflected. The uneven teeth inside his mouth did not dispel my sympathy for him. It was so guileless, that smile, like that of a little boy who has received the blessing of a father rather than a beating upon returning home full of sweat and mud. So full of hope.

He wanted something from me.

Alerted by his excess, I should perhaps have refused him, not engaged a total stranger.

Though he wasn’t entirely a stranger.

I had remarked his lanky, elegant presence already at several junctures over the past few months, at concerts offered by other musicians and at the King’s Theatre during the performances of the opera Adriano in Siria and the pasticcio Ezio, as well as at paid presentations when I myself had appeared publicly with my sister Nannerl to an explosion of acclaim, the man had been there, hovering on the outskirts of my attention. Gawking at me hungrily, never attempting to draw near, with a haunted aura, his eyes darting from me to my father, to my sister, to my mother on the rare occasions when she happened to be present, inspecting them with a gaze that was decidedly not like the one he directed at my person, as if I were a castle and they the moat, I the treasure and they the dragons.

Tonight was different—for him and for me.

Tonight he had brought along a skinny lad, close to my own age, the first thing I realized when I glimpsed him loitering in the audience, at the back of Mrs. Teresa Cornelys’s grandiose, brocaded hall. He’s brought his son tonight, I thought, must be some relative. Why, the boy brandishes a similar glum look that is just as evidently artificial.

Pathetic.

Even before I heard the man’s voice, I recognized a certain cajoling, scraping worship of power, even before he had bowed with far too much abasement as he called me “young master” in German, I recognized how he had lived, how he had survived, how someone had taught him that we cannot advance in the world unless potentates are satisfied, those who hold the purse strings and those who bestow honors and those who can kick you in the ass or lift you in their arms to glory, we cannot press forward in life unless we learn to lower our eyes and buckle our knees and insist that we are their most obedient and humble servants. A lesson my father had drilled into me. But not the only one. Because inside, Woferl, my father always insisted, inside you are free to think as you will, inside you know that you have what they do not, that God has given you inordinately more than He will ever give them. And let that certainty provide sustenance for the difficult years that are sure to greet you once you grow up and are no longer a child prodigy, once you must, as I have been forced to do, earn your bread as a musician in a merciless world.

Did that thin man now in front of me know that about himself? Had his own father taught him to keep some sense of self-worth in reserve? Or was he so famished for whatever favor I could offer that he had forgotten all dignity?

As if he could hear my inner musings, he ceased his compliments, and in a voice so squat that only he and I could harken to it, he scooted a question at me: “Can you keep a secret, Master Mozart?”

Intrigued by this unforeseen turn of events, I did not hesitate to answer in the affirmative, of course I could keep a secret.

“And are you ready, dear sir, to gallop to the rescue of an old man who has been much maligned and abused and has need of redress, can you help restore his honor?”

I nodded. It was like a fairy tale, how could I not give my assent?

“You must swear that you will tell no one of this conversation,” the man continued. “Save for one man, save for the London Bach, Johann Christian Bach, son of the incomparable Johann Sebastian, deceased these fifteen years,” and his eyes scurried in the direction of the Kapellmeister, still standing close to the podium receiving congratulations for his own newest Sinfonia Concertante, written exclusively for this subscription series. “If you were willing to accomplish this epic task, I would be evermore in your debt, as would the older man to whom I have made reference. Will you, shall you, can you, do this, young sir?”

His need was so blatant and urgent that it appealed to my kindness, how else to respond except with the affection and amiability that stemmed so naturally from my spirit, and I was about to say yes, yes, of course, dear sir, when I was struck by a chilling thought: What if he were a spy? An actor hired by my father to test me? Trust no one, Wolfgang, especially doctors, was one of his cantilenas, an eternal ritornello. Perhaps my beloved Papa had decided to use some third-rate acquaintance of Garrick’s to see if, on the first night I was away from his benevolent eye, I succumbed to the dreaded belief in the goodness of all people. Was this man’s countenance not too perfect? Had my parents—but, no, my mother would not be part of such a scheme, she would never deceive me, even for my own gain—had my father trained him, coaxed from the fellow the sort of woebegone demeanor that would reach my heart and make it melt with compassion? Directed him as if he were a town fiddler, a piper of the lowest sort? But not the lowest, no, rather a consummate professional: if this was a mask, like those I loved to parade at Carnival, it was fleshed onto his face like a second skin. No, my father could not have afforded someone of that high caliber, would not have wasted the few guineas that we barely called our own merely to test me—and anyway Papa could never have forecast that I would be left alone tonight or any other night or day or afternoon or morning or noontime without his vigilance, without his advice as to whom I should mistrust.

For once, and the first time in my life, whether I trusted this thin man or not depended entirely on my solitary judgment, not to be determined by fear of my father’s anger or yearning for his approval. It was a test, but one devised not by Leopold Mozart but by God himself, an initial lesson in how to read underneath the pleasant surface mendacity of each admirer, God teaching me to curb my outgoing personality and the automatic—and therefore far too easy—pity I feel, like a silly sponge, for any needy soul who staggers across my path, God preparing me for the day when, alone in the world, I would have to discern for myself who was my enemy and who my friend.